India needs to address massive job losses; strengthen public healthcare for COVID-19 and beyond; develop institutional mechanisms and leadership to respond to emergencies; devolve decision-making and funding to states, local bodies and scale up public spending to infuse life into the economy, all of which call for structural changes

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: May 10, 2020 | 00:07 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: May 10, 2020 | 00:07 IST

The biggest challenge the lockdown presents is massive unemployment, which the reverse migration of millions of workers demonstrates

Initial assessment of COVID-19's impact on the global economy is out. The latest issue of The Economist says the world economy shrank by 1.3% in the first quarter of 2020. It draws on different datasets to say that China's GDP dropped by 6.8% and the US's by 12% (these and most other developed economies count their fiscal year from January to December).

The magazine expects COVID-19 to leave behind a smaller economy, which it describes as "the 90% economy", for at least another 12 months because of fear and economic uncertainty. The "new normal" would be more fragile, less innovative, and more unfair (inequalities will deepen), it warns.

This is an indication of what can be expected. India needs to assess the damage to different sectors of its economy and the challenges to revive, and rebuild in view of massive reverse migration, job losses, healthcare deficiencies, and fund constraints of businesses and states.

It is clear that the revival and rebuilding exercise would entail addressing structural deficiencies too, without which it would end up as a temporary one and inconsequential in the long run.

Here are five major areas of attention for the policymakers and planners.

I. Tackling massive unemployment

The biggest challenge the lockdown presents is massive unemployment, which the reverse migration of millions of workers demonstrates. If they are desperate to return home after 40 days of lockdown and if their account is to be believed, most of them have lost their jobs and hope for rehire.

The Indian government hasn't made any assessment yet but Mumbai-based Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) which has, says the by the end of April, 72 million had lost their jobs; labour force (either working or looking for jobs) had reduced to 362 million from 434 million a month earlier; labour force participation rate (LFPR) had dropped to 35.4% of the population and the rank of those desperately looking for jobs had swollen to 85 million. These numbers are scary and are likely to worsen in May.

Unemployment was bad even before the coronavirus pandemic. The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) of 2017-18 had revealed that the unemployment rate had touched a 45-year-high; about 9 million had lost their jobs between 2011-12 and 2017-18; labour force had fallen to 495 million and the LFPR to 36.9% during the same period.

Equally worrying, the central government had neither acknowledged the employment crisis nor did anything to address it in three subsequent budgets.

Employment is critical to survival for most of the population. Going by the official estimate, 93% of workers are informal with low wages, little job, or social security. Former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan recently called them 'precariat' to reflect their precariousness or vulnerability. A good part of the formal economy also has informal workers.

What are the Indian government's plans or strategies to address job loss? Nothing is known.

Job loss is not just an individual tragedy. A massive job-loss means reduced demand and consumption, and, in turn, reduced production, investment, and slower economic recovery. If it persists for long, it also threatens social and political stability, the bedrock of economic growth.

The vulnerabilities are structural. One of the reasons for this is the acceptability of an economic theory which says higher wages will lead to lower employment. The argument goes: higher wages will lead to higher cost of products and services, demand will fall and enterprises would be forced to shed workers. Hence, for achieving higher growth wages should be low.

In practice, this concept (and other such often described as 'snake-oil economics' or deceptive and misleading) has led to (a) abysmally low wages (b) more casual than regular workers (c) little social security (d) denial of wage hike in proportion to their productivity (according to the ILO's India Wage Report, 2018, labour share, measured as GDP per worker, declined from 38.5% in 1981 to 35.4% in 2013) and (e) abysmally low national minimum wage, which was raised by Rs 2 in 2019 from Rs 176 (fixed in 2017) to Rs 178 (but not notified yet) when a government-appointed committee had recommended Rs 375 in early 2019.

II. Building public healthcare for COVID-19 and beyond

Scientific studies suggest that COVID-19 could last two or more years, warranting the continuation of social distancing for a long period. This means India needs to keep its public healthcare system robust for a long time, and not go back to its excessive reliance on private healthcare which is playing a minimal role in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.

India's public expenditure is one of the lowest in the world, lower than the average of low-income countries (India is a low-middle income country). It needs to scale up but that calls for a break with its structural rearrangement in which the balance is tilted in favour of private healthcare. This is the legacy of the 1991's liberalisation policy dictated by the World Bank-International Monetary Fund (IMF) from which it had sought loan to tide over its foreign currency crisis.

This approach has also led to two insurance-based private healthcare-driven health programmes, the Ayushman Bharat (PM-JAY) of 2018 and its failed predecessor Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna (RSBY) of 2008.

India does acknowledge that "catastrophic" health expenditure is driving "6 crore" (60 million) Indians into poverty every single year, in normal times.

Private healthcare has an important role to play in India, for sure. But for India's level of poverty and catastrophic health expenditure, it needs quality healthcare which is also affordable to its masses. That can only be possible if the healthcare is public sector-centric. Private healthcare's role can only be supplementary unless the idea is to drive more than 60 million to poverty every year.

III. Developing institutional mechanisms and leadership to respond to emergencies

It may sound politically incorrect but the absence of institutional mechanisms and leadership in responding to the current crises is too obvious to miss or ignore.

In a health emergency, the health ministers, government sector health experts, and research institutions should have been at the forefront. Most of them have been missing for most of the time, leaving the job to a joint secretary to give information as he/she wishes. Questions are restricted; answers are optional for him/her.

When the country faced severe rural distress with frequent protest marches by farmers a couple of years ago, the agriculture minister and his ministry were missing in action.

This, too, is a systemic issue.

For example, what is the labour ministry doing about migrant workers? Does it have any assessment of how many have lost their jobs and how that would impact the reopening of MSMEs and other industries and services when the lockdown is lifted? Has it in any way reached out with monetary support? These are big question marks.

The same goes for the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. Did it try to assess how many people got stranded, received food, or PDS? Did it try to identify the bottlenecks in supply and address them?

On May 2, 2020 (39 days after complete lockdown), the PMO released a statement detailing how a meeting was held "to discuss" strategies and interventions to "enable businesses to recover quickly from the impacts". It was the 39th day of lockdown. The strategies and interventions to reopen the economy should have been visible by then. More than a week earlier, on April 23, the lower house of the US Congress passed its fourth relief package to take the total relief to $3 trillion (more than India's GDP which is about $2.7 trillion) or 15% of its GDP.

The PMO or the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) isn't really supposed to do everything. That is why there are so many ministers, ministries, departments, internal research bodies and other support mechanisms. In a country of billion-plus people, it is critical that institutions work and respond to emergencies.

There could be a National Development Council (NDC) or GST Council like mechanism for emergency responses, with built-in consultation processes involving state governments, experts and opposition parties.

Unlike the US Congress, the Indian Parliament is nowhere in the scene when the country is facing unprecedented health and economic crisis.

The central government did set up 11 empowered groups under the National Disaster Management Act of 2005 to formulate plans and take steps for their time-bound implementation. What are their plans and what are they doing? Not really known. The National COVID-19 Task Force too is not very impressive in its role as investigating reports have shown recently.

Not just institutions, leadership matters too. A major deficiency was demonstrated by the Indian defence forces in their co-ordinated action of showering petals from the sky on medicos across the country for which the latter lined up and waited outside their health centres.

The time and resources devoted to these exercises could have been put to constructive and meaningful use, like arranging PPEs and test kits, the lack of which is a continued concern or could have ferried migrants stuck all over the country and indulging in periodic violence asking for trains and buses to take them home. On April 4, a group of migrants turned violent for the nth time in Surat.

IV. Devolving power and funds to states, local bodies

The state governments are at the forefront of the COVID-19 battle. They would also play an equally critical role in the revival and rebuilding of the economy.

Kerala and Rajasthan have demonstrated how effectively the pandemic can be managed at their levels. One of the keys to their success was the delegation of power to district administrations, municipalities, and panchayats for lockdowns, contact tracing, quarantine or run community kitchens. They did all this before the national lockdown was announced on March 24.

Could the panic, losses, suffering, crowding of airports, railway stations, and bus stands; migrants walking or cycling home for days and weeks, truckers abandoning vehicles carrying supplies at borders; police beating up vegetable vendors and farmers harvesting even when their activities were allowed have been less had the national lockdown announced after consultations with states, planning and allowing time for stakeholders to prepare?

This is not a hindsight view. Institutions imbibe this from past experiences.

The Union Health Ministry's COVID-19 updates show that on March 22, states had locked down 78 districts on their own and on March 23, the number had gone up to 548 districts (out of 700-plus). These show they were taking decisions on the basis of ground realities.

Even allowing this to be a hindsight view, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) could have let the states decide which shops to be allowed to open in which zone (red, orange, or green) or areas (rural or urban), instead of listing them in its May 1 notification.

That is because when it allowed shops and markets to open for the first time in its April 25 notification, one chief minister sought help in deciphering the legalese in it, another (from the ruling party) tweeted that he would decide two days later after watching the situation. Most of the shops that should have opened since then remained closed and continued to do so even after the May 1 notification because shopkeepers were not clear and too scared of the police.

Also Read:Coronavirus Lockdown III: Is India's public healthcare system prepared to fight the COVID-19 menace?

When it comes to funds, a similar situation emerges.

Several instances have come to notice in which state governments' fund sources have been limited by the central government by (a) notifying that corporates donations to the CM Relief Funds wouldn't be treated as CSR spending while that to the PM CARES Fund would (b) suspending MPLAD funds (Rs 5 crore for each MP) unilaterally, thereby denying MPs from spending in their respective states (c) delaying GST disbursements about which multiple complaints have been made and (d) centralising procurement of PPEs and health equipment from the Rs 15,000 crore health emergency fund.

These are not efficient ways of handling crises nor reviving and rebuilding the economy.

V. Scaling up public spending to infuse life into the economy

Economists are unanimous that the COVID-19 pandemic calls for loosening the purse and keeping fiscal austerity aside in the current crisis.

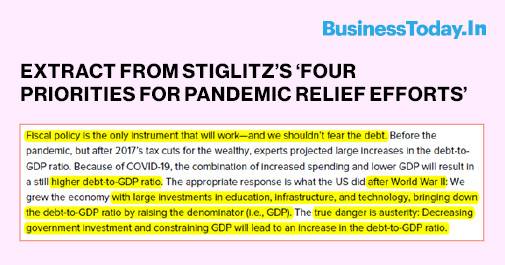

Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, who was once part of the global drive for fiscal austerity, wrote a paper 'Four Priorities for Pandemic Relief' on May 1 telling the US that "the true danger is austerity" at this time. He advised (reproduced below) higher government investment in education, infrastructure and technology to boost growth because not doing so would be counterproductive and slow down GDP growth.

Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee has been consistently advocating opening the fiscal gate and spending more. So is former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan. States are demanding relaxing fiscal deficit norms from 3% to 5% of their GDP.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), the main driver of fiscal austerity, has already abandoned it even for normal times. Its own top three economists wrote in their 2016 study 'Neoliberalism: Oversold?' that "...in practice, episodes of fiscal consolidation have been followed, on average, by drops rather than by expansion in output. On average, a consolidation of 1 per cent of GDP increases the long-term unemployment rate by 0.6 percentage point and raises by 1.5 per cent within five years the Gini measure of income inequality."

That fiscal deficit leads to inflation only when there is full employment and full production is a well-known prescription of Keynes. The current conditions in India, and elsewhere, are exactly the opposite.

This, again, calls for structural rearrangement because the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act of 2003 puts severe restrictions.

No comments:

Post a Comment