The global fight against health and economic crises highlights the need for big government spending and better redistribution to protect people, not less

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: June 6, 2020 | 17:44 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: June 6, 2020 | 17:44 IST

In 2018, India's general government expenditure (Centre and states combined) was just 18.2% of its GDP

On June 5, when the US recorded more than 1.1 lakh deaths from COVID-19, maintaining lead and accounting for 28% of all such deaths in the world, Nobel laureate Paul Krugman revealed something about the US's health system few outsiders know.

In an article in the New York Times, he wrote, "Non-American friends sometimes ask me why the world's richest major nation doesn't have universal health care. The answer is race: We almost got universal coverage in 1947, but segregationists blocked it out of fear that it would lead to integrated hospitals (which Medicare did do in the 1960s.) Most of the states that have refused to expand Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act, even though the federal government would bear the great bulk of the cost, are former slave states."

And then, he adds, "The Italian-American economist Alberto Alesina suddenly died on March 23; among his best work was a joint paper that examined the reasons America doesn't have a European-style welfare state. The answer, documented at length, was racial division: in America, too many of us think of the beneficiaries of support as Those People, not like us."

That discrimination can cause havoc even in one of the wealthiest countries needs no further elaboration. It is there for all, including India, to see and learn from.

The European model versus the US one

The work Krugman refers to was published in 2001 by Harvard University, 'Why Doesn't the US Have a European-Style Welfare State'. The concluding paragraph of it puts the findings very succinctly and is reproduced below.

It had found many more outcomes which are relevant. It said "post-tax income inequality is lower in countries with large governments and in particular, with large social spending", adding that "it is pretty clear that income inequality is lower in Nordic countries, intermediate in central and southern Europe, higher in the UK and even higher in the US".

The situation remains unchanged since then.

A 2019 OECD study shows that the average social spending of its members (37 countries, including the US and European countries) was above 20% of GDP in 2018. Many European countries like France (more than 30%), Belgium, Finland, Denmark, Italy, Sweden, Germany, Norway and even the UK (just above 20%) spent more than the average, while the US spent less.

India's social sector spending is awfully low in comparison. India has been spending (Centre and states combined) less than 8%. The health sector spending has remained at 2.8-3.2% since FY12.

The size of government is measured as general government expenditure relative to the size of economy of a country (GDP).

The OECD database shows the average size of government in 2018 in 28 member countries (for which data is available), was 43%. Many European governments were spending more than 50% of their respective GDPs (like France, Finland, Belgium, and Denmark). The US was, again, in the bottom pile with 38%.

The US is considered a 'small government'. India is even smaller in comparison.

In 2018, India's general government expenditure (Centre and states combined) was just 18.2% of its GDP. Since FY12, the number has been confined to a narrow band of 17.2-18.4%.

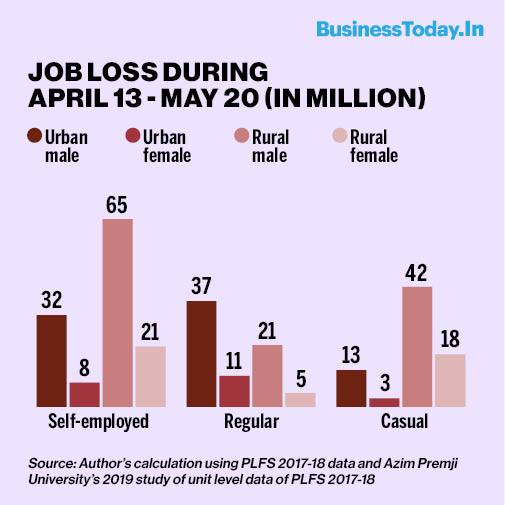

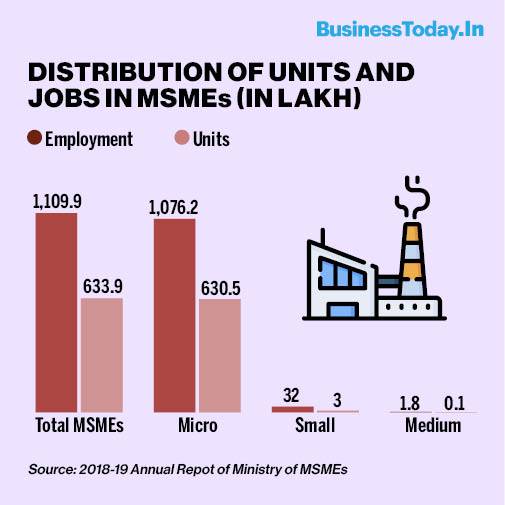

The impact of low social sector spending and small government is evident in India now. The plight of the migrants, fleeing in millions back to their villages for weeks, some of them walking hundreds of miles with kids and elderly, is one.

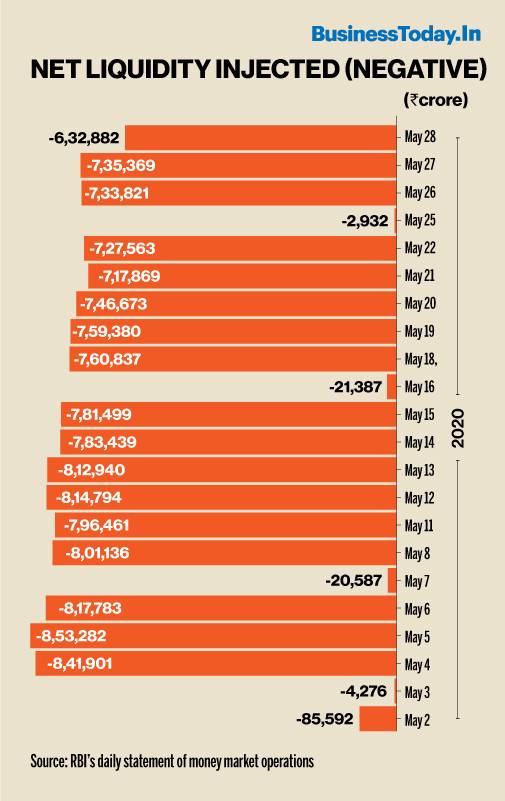

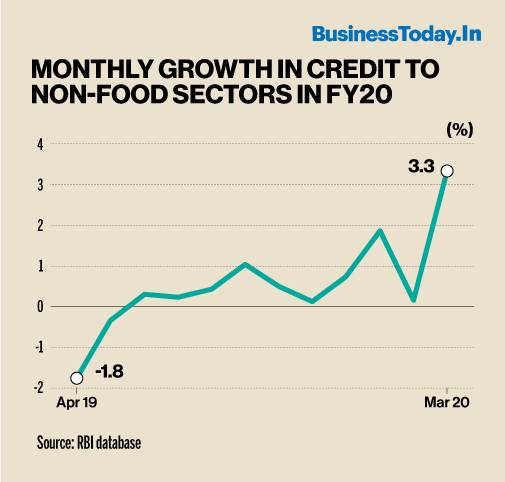

The second is gross inadequacies of its healthcare system exposed by the virus and the third is its inability to provide a big fiscal stimulus (fiscal spending announced in its relief packages amount to just 1% of its GDP) which is needed to kick-start the locked down economy.

One caveat is in order. Economists attribute the low government spending in India (small government) to its relatively lower tax revenue. India's tax-to-GDP ratio is less than 20% (Centre and states combined).

In FY19, it was 18.5%. For the OECD countries (which comes closest to India's FY19), the average was 34.3% in 2018 (of 34 countries for which data is available). Here too, the US lagged behind with 24.3%.

Small government is not beautiful

A few days earlier, when the US was about to record 100,000 deaths, another Nobel laureate, Joseph Stiglitz had spoken about the US's broken healthcare and other shortcomings in handling the crisis.

In an interview (on May 26), he said, "I think Americans have become aware as a result of the pandemic that there are some aspects of our economy and our society that aren't functioning well, that we don't have a functioning healthcare system, that the pandemic has gone after people in poor health and we have so many more of those people in the US than you'd expect in a rich country."

He pinned the ills on 40 years of economic thinking that denigrated the role of government (advocating small government) while allowing unrestrained market forces to prevail. This is not restricted to the US alone but has spread to other countries too.

He suggested a course correction, reminding that while it is the duty of governments to handle the crisis; the market isn't geared for it.

It is fairly known that a strong push for small government came in 1980s when multilateral US-based agencies like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) played a key role (read Coronavirus Lockdown XVII: The economics behind India's Rs 21 lakh crore package).

In this economics, there is little room for the European-style welfare state which spends more on social security (redistributes more) and has big governments. But the IMF has begun to see merit in it.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world, it published a paper in December 2018, 'Shifting Tides: Dramatic social changes mean the welfare state is more necessary than ever'. It found the welfare state as a means to absorb the risks that market failure can produce.

In all, it cited three reasons for this shift in thinking, as reproduced below.

Talking about healthcare risks, it says the US is "unique among advanced economies" to rely on private actuarial insurance to address its health risks while "it is almost universally accepted among advanced economies that intractable market failures make private actuarial insurance a bad fit for medical risks..."

Also read: Coronavirus Lockdown XVI: Why India should be wary of excessive push for liquidity or credit

Health economist Dr. Indranil Mukhopadhyay of OP Jindal University explains what private actuarial insurance is and why it is prone to market failures.

About the insurance model, he says, "The private voluntary insurance that we buy for us and our families works on calculation of risks, a method called actuarial science. To put it simply, it estimates the financial risks of say, hospitalisation, for the population. The actuarial premium to be paid is the average cost of care adjusted for diverse risks of falling ill. In practice, however, management and administrative costs and profits are added ('overload'), increasing the premium."

About the associated market failures, he states, "There are well-known market failures of such voluntary health insurance. First, in order to make profit, such schemes work on exclusion and claim rejection. They tend to include healthy and young people and exclude the needy ('cream-skimming'). They reject a lot of claims and expect patients to bear a part of the cost; people are thus denied care or end up paying huge bills.

Also Read: Coronavirus Lockdown XV: Not just stimulus 2.0, getting fiscal mathematics right is critical too

"This is very common in the US and in India. The main purpose of risk pooling, financial protection, and free care thus gets defeated. Moreover, it creates monopolies in the hospital market; big hospital chains eat up the small ones, and cost of care increases further."

A US-based doctor explains the consequences for the US in simpler words: Health costs are very high even for the young and many, like the unemployed and poor don't have health insurance cover and are deprived of healthcare.

Newspapers have been highlighting the plight of US citizens fighting the pandemic. One particular article in The Guardian sums it all up well in the headline, "Profit over people, cost over care: America's broken healthcare exposed by virus".

India needs to be on guard against following the same path.