Even in normal times, private healthcare has played truant. In the current health crisis, its role is neither proportionate to its dominant presence nor call of duty. If public healthcare carries almost the entire burden on its shoulders then it is imperative to nurture it, rather than neglect it

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: April 29, 2020 | 20:06 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: April 29, 2020 | 20:06 IST

India has actively promoted private healthcare post-1991 liberalisation

For decades India has been promoting, pampering and partnering private healthcare with cheap land, tax reliefs and other assistance, often at the cost of public healthcare. Its share in national healthcare needs surpasses that of public healthcare by a big margin and yet when a national health emergency hits, it is on the margins.

Most private hospitals and nursing homes have shut shop, forcing authorities of some states to issue orders and warnings. Those in the field have mostly been requisitioned through imposition of the National Disaster Management Act (NDM) Act of 2005, rather than volunteer help.

Is that shocking or surprising?

Here is what happened when many of us were sleeping.

Appeal during national health emergency

On April 16, the CEO of Ayushman Bharat (PM-JAY), Indu Bhushan wrote an article in a national daily with an interesting headline: 'Private sector must be a wholehearted partner of government in fight against COVID-19'.

It ended thus: "Consider this as an appeal to all private and charitable healthcare institutions to join this effort. This is the time to play our individual and collective roles in the fight against COVID-19. In this moment, like King Lear, "(t)he weight of this sad time, we must obey," because "nothing will come of nothing."

This is rather odd.

For one, Bhushan doubles up as the CEO of National Health Authority (NHA) and is authorised to tie-up with private healthcare. As the CEO of PM-JAY, he has already been doing precisely that for two years (appointed in March 2018). For another, on March 25, the Indian government invoked the NDM Act of 2005 which empowers the "requisition of resources" of private sector during a crisis (clause 65).

This requisition is not for free; there is a provision for "compensation".

Pampering in normal times

India has actively promoted private healthcare post-1991 liberalisation. It now provides 70% of national healthcare needs and also accounts for 60% of funds disbursed under the PM-JAY programme, Bhushan disclosed in his article to coax private healthcare into action. He wrote how private healthcare "should be the core of national health effort", that India is passing through "century's biggest crisis" which calls for "need to work in tandem" and that it is "not a race to a hilltop".

Not long back, the Indian government was doing everything in its power to promote private healthcare at the cost of public healthcare.

For example, in her budget speech on February 1, 2020, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman (a) proposed handing over government-run district hospitals to private medical colleges and (b) sought land at concessional rate from states to facilitate private medical colleges in public-private partnership (PPP) mode. She promised viability gap funding (VGF) to states for their full cooperation without explaining what she meant by it.

A year earlier (January 2019), the Health Ministry had asked states to provide 40% VGF and "unencumbered" land for setting up private medical colleges. A month earlier (January 2020), the Niti Ayog had proposed a PPP policy for health in which private healthcare was to "upgrade, operate, and maintain" government-run district hospitals.

Taken together, the three steps meant setting up private healthcare with public support.

Not once did the word 'appeal' found a place in any of these moves.

Seeking help for itself when its help is required

By the time Bhushan's article appeared, private healthcare had spoken, and how.

A day earlier, on April 15, industry body FICCI issued a statement, 'COVID-19 pandemic leaves the private healthcare sector in financial distress: FICCI-EY study'.

It quoted Sangita Reddy, FICCI president and Joint MD of Apollo Hospitals Group, as saying: "The private healthcare sector in India has stood beside the government firmly to contain the virus and is deeply committed to the war against COVID-19. However, there is an urgent need to consider the healthcare industry's triple burden viz., low financial performance in pre-COVID state; sharp drop in out-patient footfalls, diagnostic testing, elective surgeries, and international patients across the sector is impacting cash flow; and the increased investments due to COVID-19; which has impacted the hospitals and laboratories like never before."

Not a word was said on how private healthcare had stood firmly in the crisis but the statement contained a litany of its woes and appeal for help.

Pointing to a study conducted in collaboration with consultancy firm Ernst & Young, it said COVID-19 had led to 70-80% drop in footfall, test volumes and 50-70% drop in revenues in just 10 days and expected the situation to continue.

It estimated operating loss of Rs 14,000-24,000 crore in the first quarter and added a wish-list: "need liquidity infusion, indirect and direct tax benefits, and fixed cost subsidies from the Government to address the disruption".

No free COVID-19 tests by private labs

On April 8, 2020, the Supreme Court directed private labs to conduct free COVID-19 tests (RT-PCR) when it was pointed out that the cost fixed for it (Rs 4,500) was prohibitive. The court reasoned: "Private hospitals including laboratories have an important role to play in containing the scale of the pandemic by extending philanthropic services in the hour of national crisis".

It was met with a volley of protests from the private sector. An appeal was filed. On April 13, the court modified its order saying free tests would be available only to those eligible under the PM-JAY scheme, which is paid for, or others for which the central government would have to first set up a mechanism for "reimbursement to the private sector".

What made the SC change its mind? Mukul Rohtagi, former topmost government law officer (Attorney General during 2014-17), told the court that it would be "impossible" for private labs to provide free tests due to "financial constraints and other relevant factors".

Tushar Mehta, serving Solicitor General (second topmost government law officer) said 10.7 crore poor and vulnerable families were already being provided free tests under the PM-JAY and that the government was taking all necessary steps.

The government is yet to explain how it came to fix Rs 4,500 for COVID-19 test, other than that it did it in consultation with the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR).

Doubts have been expressed across many quarters that the cost is on the higher side. This was reinforced after Dr. A Velumani, Chairman, CEO and MD of Mumbai-based private lab Thyrocare Technologies, told media that he was making a net profit of Rs 1,000 per test. He said his operating cost came to Rs 3,500. This revelation came amid backdrop claims by other private labs that Rs 4,500 barely covered their operational cost and that COVID-19 test was a CSR activity, or social service, for them.

This claim (CSR activity or social cause) reminds one of a 2018 Supreme Court judgement in which the court gave private healthcare a history lesson.

Playing truant even in normal times

That case, Union of India versus Mool Chand Khirati Ram Trust, involved some of the prominent private hospitals of Delhi which had been violating a legally mandated rule to provide free healthcare to the poor in lieu of land at concessional rate. They are to provide 10% of indoor and 25% of outdoor (OPD) care free but didn't.

The court reiterated its earlier order to do so forthwith, but not before giving them a lecture.

The court took them back in 1949 when the government first decided to provide all possible help to private players, including allotment of land at concessional rate, to build and operate hospitals and schools "to achieve the larger social objective of providing health and education to the people".

It took them through the logic of why certain private institutions were selected for the purpose but not others and also reminded that in 1996, private players were being told that government help was for "serving the public interest", not "to make money or profiteer".

Those weren't the only occasions. The Supreme Court did it in 2011 too.

On its part, the Delhi High Court has been ordering compliance from private healthcare year after year without much impact. A Delhi legislative committee went into the issue and submitted its findings on December 3, 2019. Here are some of its findings.

In 2002, the Delhi High Court first ordered private hospitals of Delhi to pay back the "unwarranted profits" they made by violating land allotment condition of providing 10% of indoor and 25% of outdoor (OPD) care free of cost to poor.

The private hospitals disobeyed it. In 2007, the court expressed its unhappiness and set up a "special committee" to work out unwarranted profits made by 20 private hospitals.

The "special committee" issued "recovery orders" to five private hospitals, ranging from Rs 10.6 crore to Rs 503 crore, depending on the duration of their operations. The hospitals went for appeal, following which they were ordered to deposit "interim amount" with the registry of the court.

The Delhi legislative committee said until finalising its report (December 2019), it had no idea how much money had actually been recovered from those private hospitals. It concluded: "Most of the private hospitals...are violating the directions of the GNCTD (Delhi government) and the Hon'ble High Court in this regard."

This is when, as a former tax officer says, health (and education) services are almost entirely tax-free.

In the time of COVID-19

Now that the country is fighting COVID-19, most of the private hospitals and nursing homes are shut.

Some of the big private hospitals of Mumbai closed down after some of their staff were found infected, a turn of events unheard of in public healthcare. On April 25, the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) warned private healthcare to open for non-COVID patients or face action. A few days earlier, the Bihar government had ordered the same.

For some of those that are open, it is business as usual. Several complaints about profiteering have come to notice. On April 24, a Mumbai newspaper reported that a private hospital charged a patient Rs 80,000 for 8 hours of COVID-19 treatment. He later died. Social media has been circulating COVID-19 test bills showing far higher than Rs 4,500 being imposed in the name of 'registration', 'consultation' and 'handling' charges etc.

Given this background, does Indu Bhushan expect his appeal to work?

Doesn't the very fact that he had to issue a public appeal on April 16 reflect failure of his private efforts?

Here is how eminent public health scholar Dr. Sakthivel Selvaraj of the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) sums up the current healthcare in India:

"India has perhaps the largest private healthcare market in the world, both in terms of financing and provision of care. Its inefficiency and inequity in healthcare is often more apparent than anywhere else. The current scenario under COVID-19 is only a reflection of the system in which private sector hesitates and is unwilling to participate, leaving the hapless patients and the government to bear the burden.

"In an acute situation where private sector participation is far more required, their dithering and hands-off approach is not only callous but calls for a rethink on the part of the government to rejig its strategy of utilising taxpayers' money to procure healthcare services from them. COVID-19 is a wake-up call to move towards nationalisation of healthcare services."

Postscript: In the meanwhile, two quick developments have taken place. On April 24, the Delhi High Court cut down the cost of COVID-19 rapid test kit (antibody test) from Rs 600 (excluding GST) to Rs 400 (including GST), stating that "public interest must outweigh private gain", after discovering a massive mark-up in the supply price.

Also Read:Coronavirus Lockdown III: Is India's public healthcare system prepared to fight the COVID-19 menace?

Following this, the ICMR tweeted on April 27 that the price range approved for the RT-PCR test (coronavirus test) was Rs 740 - Rs 1150, not Rs 4,500. If the upper limit is Rs 1,150, then how and why was the cost fixed at Rs 4,500 for private labs has not been explained yet.

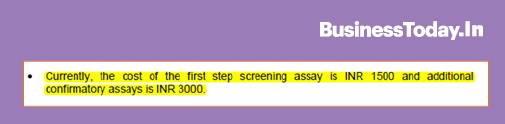

That the ICMR is not clean is clear from the fact that on March 27, 2020, it had issued a statement, "Strategy of COVID19 testing in India (17/03/2020)", which clearly spelt out the two-step testing procedure in RT-PCR, the cost for the first one being Rs 1,500 and for the second Rs 3,000, taking the total to Rs 4,500 - as reproduced below.

The tweet also mentioned that the cost for the rapid test approved by it was in the range of Rs 528 -Rs 795, clearly revealing that it was marked-up.

No comments:

Post a Comment