Decades of low public investment has denied a large population access to quality healthcare. High out-of-pocket costs are driving millions into debt and poverty every year. Here is a chance to redesign the system keeping both affordability and quality in mind

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: April 3, 2020 | 13:05 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: April 3, 2020 | 13:05 IST

If the novel coronavirus can wreak havoc in the developed countries with far superior healthcare, India is surely sitting on a time bomb

That India's healthcare system is grossly inadequate to provide quality infrastructure and manpower to millions of its citizens is well known. What the COVID-19 pandemic has done is to bring a sense of urgency to fix it. If the virus can wreak havoc in developed countries with far superior healthcare, India is surely sitting on a time bomb.

A glaring evidence of this inadequacy is reflected in an abysmally low number of COVID-19 tests India has carried out. The Health Ministry does not provide data on the number of tests. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), the apex body of biomedical research, did it and then stopped on the morning of March 27. At that point the number read: 27,688.

This was three days after the country was locked down for 21 days. By then, 691 had been found positive and 17 dead.

Big risk from reverse migration

A far bigger threat now stares in the face.

The ICMR did say a few days ago that there was no community transmission of the virus yet but the situation could change overnight with millions of migrant workers heading home due to loss of jobs, shelter (small industries and landlords apparently asked them to vacate) and fear of starvation.

The crowding of inter-state borders for days in many parts of the country has the potential to undo any gain India may be expecting from 'social distancing. Panchayats, talukas and districts can hardly be expected to effectively quarantine a large population, provide food and medical support. What happens next is a scary scenario.

India did realise the poor state of its healthcare when the COVID-19 scare hit home. Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared allocating Rs 15,000 crore to improve healthcare even as he announced the 21-day lockdown. Most part of the fund would, presumably, go into meeting the emergencies, import of safety and testing kits, ventilators etc.

What part of it goes towards rebuilding healthcare, and how, is not known yet. But when such an exercise is carried out it would require a better understanding of the ground realities.

Here are some of the most critical ones.

Access to quality care for the vast majority holds the key

It is not enough to build a quality healthcare system if it is not accessible to millions of India's citizens. How poor is the accessibility? Here are some pointers.

The Global Burden of Disease study of 2016 (GBD 2016), published in the medical journal Lancet in 2018, put India at number 145 among 195 countries (including sub-Saharan Africa), in the Healthcare Access and Quality (HAQ) Index. India's score was 41.2, against the global mean value of more than 60, and lower than some of the neighbours like Bangladesh, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Bhutan.

That is because of high out-of-pocket expenditure (OOP)-the amount of health expenditure paid from the pocket of individuals as a percentage of total public healthcare expenditure of a country.

What is India's OOP level?

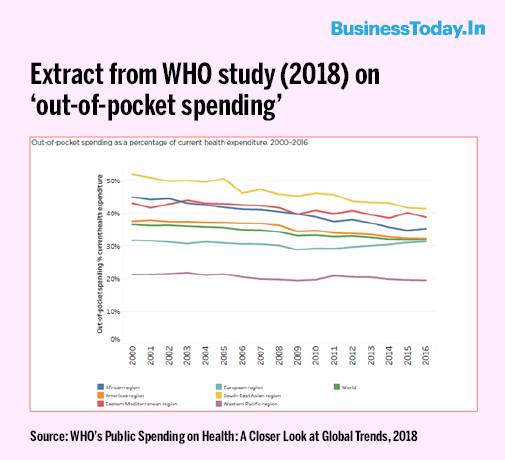

The World Health Organisation (WHO) data shows India's OOP stood at 65% in 2016, the last year for which the comparative data is available. For the same year, the global OOP average was a little over 30% (green line in the graph below) and for the South East Asia region (at the top), a bit over 40%, according to a WHO study published in 2018.

India has a long way to go.

Poor public investment in healthcare

What is clear from the above graph is that India has largely left its citizens to fend for themselves by gradually retreating from healthcare (also education), especially after the 1991 liberalisation.

Though this is a global trend, India is an outlier.

The latest National Health Profile 2019, released in October 2019, shows India's public expenditure on health (centre plus state) has been less than 1.3% of the GDP for many years.

The NHP 2019 also shows how India's public investment is one of the lowest in the world, lower than even the 'low-income countries'. (India is in the 'lower middle income' category)

High cost driving millions into debt and poverty

Low public investment in healthcare has its human costs.

Way back in 2011 a study published in the Lancet, Health care and Equity in India, first alerted India by showing that 39 million people were falling into poverty every year because of high out-of-pocket (OOP) spending on healthcare.

Again in 2018, another study published in the British Medical Journal said that in 2011-12, 55 million Indians fell below the poverty line due to OOP. Of this, 38 million fell into poverty due to medical costs alone.

These studies failed to wake up India all these years.

These studies are also important for providing one big answer to why a large population of Indians perpetually lives below the poverty level despite decades of economic growth.

Public sector or private sector-led healthcare?

Going by the data and studies presented so far, it is clear that what India needs is a quality healthcare system which is affordable to most of the Indian citizens. This can only be ensured by a healthcare model that revolves around the public sector, not the private sector.

Just one example would suffice.

When the central government asked the private sector players to chip in for the COVID-19 tests, it fixed the cost of such tests at Rs 4,500 ($60 at exchange rate of Rs 75) to prevent exploitations.

What would be the cost of treatment in a private facility which may involve the use of a ventilator or COVID-19 vaccine or some other treatment that may be developed? Surely, several times more than Rs 4,500. With a per capita income of about $2,010 (2018), how many Indians would be able to afford such a treatment in private care?

In recent years, India has switched gears. From neglecting public healthcare, it has started building private healthcare with public money and other support.

Here are some recent instances.

Public money, private healthcare

In September 2018, India took a major initiative in healthcare when the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Abhiyan (PM-JAY) or the Aayushman Bharat was launched.

It aims to provide hospitalisation cover (insurance) of up to Rs 5 lakh to 10 crore poor and deprived families (about 50 crore people). It is fully funded by the taxpayers' money (Centre and states share funds at 60:40). The central budget of 2020-21 earmarked Rs 6,400 crore for it.

There is no study or assessment yet to establish its efficacy, but the PM-JAY has sparked conflicts between the Centre and states. Here are the reasons.

In January 2019, the Health Ministry issued a 'Broad guideline for private investment in the setting up of hospitals in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities subsequent to PM-JAY'.

It asked the state governments to do three things for the private investors in healthcare: (i) earmark and provide land within specific times (ii) facilitate administrative clearances and (iii) provide 40% viability gap funding (VGA) - advance payment from the exchequer (taxpayers' money) to help build the private facilities and provide gap funding up to 50% of tax on various costs, including capital cost, granting the status of industry to hospitals for ensuring that VGF is provided.

Apparently, it had few takers and there was little progress. Nevertheless, the central government pressed forward.

A year later in January 2020, the Niti Aayog brought out a public-private participation (PPP) plan envisaging handing over the government-run district hospitals to private players (who were to be given 40% VGF, land and various concessions as per the January 2019 guideline).

Called "Scheme to link new and/or existing Private Medical Colleges with functional District Hospitals through PPP", it said the following.

It may be pointed out here that India abandoned the PPA model many years back for failing to bring in private investment but contributing significantly to the growth of NPAs (bank loan defaults). The PPP model has long gone out of public and policy discourse.

Nevertheless, the Budget 2020 chipped in, saying that the states that "fully" cooperate in its efforts to promote private healthcare will be rewarded with VGF (a notorious UPA era mechanism that drained public resources to private players for doubtful public gain).

The governments of Kerala and Madhya Pradesh have strongly opposed the move. India's apex body of medical professionals, the Indian Medical Association (MCA), too has opposed it. The IMA's secretary-general Dr RV Asokan says the PM-JAY "is yet to take off".

But that is not why he is opposed to the central government's plan to handover public (district) hospitals to private players.

Public healthcare for public service

Dr Asokan says whatever India has achieved in its fight against COVID-19 so far is due to its public healthcare system: thermal screening and surveillance at airports, contact-tracing, tests and the process of quarantine. Going forward, a bulk of the burden would be shouldered by the public healthcare resources, from community level (ASHA) to panchayat, district, state and central levels. Now that India is talking about dedicated COVID-19 hospitals, the public healthcare system is even more important, he adds.

His explanation, "Suppose we didn't have public hospitals at the district level. What would have happened? What hold would the government have on the situation if we enter into the third stage of fighting the COVID-19 (i.e., treatment) and the entire healthcare setup is with the private sector? The government would have to take over these healthcare centres to get control over the situation."

"That is exactly the case in the US where the federal government has no control over hospitals. Many Americans may be denied access to treatment for not having health insurance," he adds.

Building for the future

By all accounts, the fight against COVID-19 would be a long haul. Experts say the virus would survive for several months after "flattening the curve" (slowing down infections) that India aims to achieve through social distancing.

This would mean India can't afford to restrict itself to a few weeks of emergency measures. It would have to think long-term and plan for future exigencies, something that calls for redesigning its healthcare system to respond to people's needs.

No comments:

Post a Comment