The government gives guaranteed return to private companies in its business dealings and considers their profit-motive good and desirable. Why the same doesn't hold true for farmers?

Prasanna Mohanty | January 25, 2021 | Updated 18:25 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | January 25, 2021 | Updated 18:25 IST

The protesting farmers' demand for trade at guaranteed minimum support price (MSP) outside the APMC-run mandis seems so outlandish that, let alone the central government, even economists sympathetic to the farmers' cause are reluctant to support it.

Is this really such an un-business-like proposition?

Here is a reality check.

Guaranteed return (profit) to private businesses

In April 2016, the Centre's Department of Economic Affairs (DEA) released a document titled "PPP Guide for Practitioners". It declared that this document was prepared by the PPP Cell of the department, in which experts from the government and private sector "participated enthusiastically" in review and consultation exercises before it was finalised.

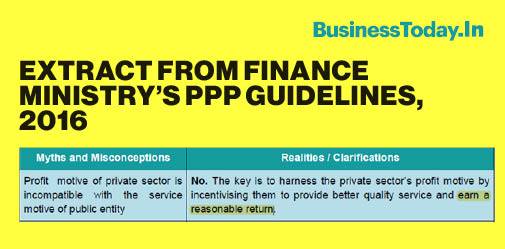

On page 30, it explains "Myths and Realities about PPPs" through FAQ-type questions and answers. ('PPP' stands for public-private participation in which government partners with private companies in development activities, particularly in infrastructure.)

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 60: India in a financial mess of its own making

The first question and its answer are reproduced below.

Does a word of it read out of place?

No. Firstly, because "profit motive" of the private sector is taken for granted and appreciated, and secondly, assuring a "reasonable return" (profit) to private businesses is considered desirable in order "to harness" that motive.

Now replace "private sector" with "farmers" and see how public servants and economists react. The entire construct would fall apart, as is happening now with the demand for guaranteed MSP outside the APMC mandis.

The privileges granted to the private sector (enthusiasm in prior consultations and reviews, reasonable returns/profits) are not available to farmers who, incidentally, feed every Indian, including the reluctant public servants and economists, even when the three new farm laws seek to drastically change the rules of farming, trading in and hoarding of farm produce unilaterally, behind the back of farmers and state governments (agriculture is a state subject).

This is not DEA's isolated construct.

Here is another example from the DEA's document published in December 2010 ("Public Private Partnership Projects in India") containing 12 case studies of PPP projects across India covering road, water supply, port, metro, power distribution, etc. the contracts for which are typically signed for 30-35 years and are in build-operate-transfer (BOT) mode.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 59: Quantum jump in fiscal spending is what India needs immediately

This document tells "reasonable" and "assured" return/profit of 20% is guaranteed to private sector partners, which is inflation-proof, and additionally, in case this profit is not realised, the contract period is extended by a few years to ensure it.

The Niti Aayog, as also the health ministry, has been a champion of PPPs in healthcare even during the pandemic, repeatedly writing to state governments to handover their district hospitals to private medical colleges, facilitate unencumbered land, and also 40% viability gap funding (VGF) for building these private medical colleges.

The VGF would be reimbursed from the central government's Aayushman Bharat fund, the states have been told. In her 2020 budget, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman also urged states to do so. (For more read "Coronavirus Lockdown VI: How India's insurance-led private healthcare cripples its ability to fight COVID-19 " & "Coronavirus Lockdown XVIII: Why India urgently needs SOPs for decision-making ")

The Niti Aayog's 2018 PPP project guidelines for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in district hospitals too repeatedly talk about "reasonable" return (profit) and need for "periodic revision of tariffs (to be paid to private partners) in a predictable manner due to cost escalation".

It is a different matter that PPPs and VGFs in the infrastructure sector caused incalculable damage to the banking system by way of loan defaults, availing loans far in excess of the approved project costs and contributed significantly to the NPA crisis during the UPA regime.

By the end of the UPA regime, PPPs and VGFs had virtually become untouchables. When the NDA-II came to power, both were revived and the 40% VGF extended till FY25. (For more rad "Rebooting Economy 46: Who is designing India's growth path? " & "Rebooting Economy XII: Is private sector inherently more efficient than public sector? ")

Here is an instance relating to farm produce.

A few years ago, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) signed a contract with a big private business house to build and operate silos to store food grains on its behalf in several states with a fixed and guaranteed rent for 30 years with provisions for inflation-proofing and periodic revisions.

State governments have been signing power purchase agreements (PPAs) with private sector companies with a guaranteed return (profit) since 1990s.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 58: The untold story of India's services sector

Old times would recall how Enron's Dabhol project in Maharashtra was signed in 1990s (multiple times, actually) with an assured return (profit) of 25.2% when the norm was 16%, and at a high rate for power (per KWH), almost ruining the state government's finances.

The states went to courts for relief several times. The central government had given a sovereign guarantee on the assured payment and return to Enron too, in case the state defaulted.

The questions that need to be asked are: If the central government guarantees risk-free, fixed rate of return (profit) to private sector companies in its business dealing, and advises state governments to do so, why is it reluctant to abide by the same principle for farmers? Why should private sector companies refuse to guarantee a reasonable and assured return to farmers?

The MSP is decided by the central government, not farmers.

Two more questions are also relevant here: Why shouldn't guaranteed MSP be a part of the law that allows trade outside the regulated APMC-run mandis to ensure "reasonable" and "assured" return or profit to farmers? Who and what else will ensure farmers are not short-changed when exposed to unregulated market?

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 57: When and how will industry take India to next level of growth?

For the uninitiated, free-market hasn't been fair to farmers anywhere in the world.

Here is how.

Farm subsidies in free-market economies

The following table on farm subsidies was shared by Kaushik Basu, former chief economic advisor in the Manmohan Singh government and former chief economist of the World Bank, on his Twitter handle on January 16, 2021. As can be seen in the table, major economies in the world give far bigger farm subsidies than India.

Had free-market been kind to farmers, the champions of free-market economies like the US and EU wouldn't be doing this, would they? Incidentally, unlike these free-market champions, more than half of India's agricultural workforce is landless and of the rest, 86% are small and marginal farmers with less than 2 hectare of landholdings.

Basu shared the table with a caution: "In discussing agricultural policy & government support, it is important to keep in mind that we live in a globalised world. What is good policy cannot be decided in isolation. You need to be mindful of what economies around the world are doing. Here is a sampler".

Not just low farm subsidies compared to free-market economies, Indian farmers have other reasons to feel aggrieved.

How Indian farmers are short-changed

In India, the MSP is declared for 23 crops but procurement at MSP is limited to wheat and paddy by the FCI. A few other government agencies procure some amount of other farm produce. The Agricultural Statistics at a Glance, 2019 provided this data on those procurements for 2018-19: Coarse grains (0.2 MT), pulses (4.3 MT), oilseeds (1.6 MT), cotton (1.1 million bales), and jute (73,000 bales). Not all states benefit from it. (For more read "Rebooting Economy 54: Will bypassing APMC-based procurement improve farmers' income, ensure food security? ")

Despite repeated promises since 2014, the central government hasn't fixed MSP that the Swaminathan committee, set up in 2004, recommended. It sought MSP on comprehensive cost of production plus 50% profit (C2+50%), which would include land rent and interest paid on capital investment as input cost.

Had this formula been adopted, eminent economist Prof. RS Ghuman of the Chandigarh-based Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development (CRRID) estimates that Punjab farmers alone would have received additional income of Rs 14,296 crore in a year for wheat and paddy crops.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 55: Farmer producer organisations best bet for small, marginal farmers

Imagine how farmers would have benefited across India had the Swaminathan formula been implemented, or MSP-based procurement was carried out for all 23 crops.

There is an additional reason to ensure assured income for farmers.

Prof. Ashok Gulati, a member of the Supreme Court-appointed committee to look into farmers' demands and former chairman of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), co-led a2018 OECD-ICRIER study, "Review of Agricultural Policies in India".

It calculated how much income Indian farmers are losing because of India's complex market regulations and restrictive trade policies, despite farm subsidies.

What it found was astounding: Indian farmers lost Rs 2.65 lakh crore per annum, at 2017-18 prices or Rs 45 lakh crore cumulatively for 17 years between 2000 and 2016. (For more read "Decoding Slowdown: Govt apathy and low investment continue to plague the agriculture sector ")

Low farm income, high debt, and suicides

How have government policies impacted farmers over the years?

The Niti Aayog's 2017 "Doubling Farmers' Income" report presented a graph showing 22.5% of Indian farm households live below poverty line (BPL). In some states like Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh, the numbers went up to 30% to 45%.

It is no secret that farmers have low incomes.

The last assessment of farmers' income was made by the NSSO's 70thround of survey (Situation Assessment Survey) which collected data for 2012-13 and published its findings in December 2014. (Despite promising to double farmers' income since 2014 and setting up a committee to recommend measures, the NDA-II government has not collected any data on farmers' income.)

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 53: Why crop insurance is losing traction in India

The report said the monthly average income of farm households was Rs 6,426 (in 2012-13). The Dalwai committee (DFI), set up by the NDA-II to double farmers' income, said in one of its 2017 reports that at 2011-12 prices, the above monthly average income worked out to be Rs 5,843 per month.

How do farm households fare when compared to non-farm households in income?

The only study that does this is very old too. Prof. Ramesh Chand, currently a Niti Aayog member, and his colleagues estimated the income of cultivators (farmers) and non-farm workers and published their findings in the Economic and Political Weekly way back in 2015.

Prof. Chand has not updated his estimates although he has been a Niti Aayog member since 2015.

Here is another shocker.

The NSSO's 2014 report mentioned earlier, looked at farmers' indebtedness too and estimated that the average debt on each farm household was Rs 47,000-7.3 times the average monthly income of Rs 6,426.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 52: The unfinished agenda of land reforms nobody talks about

States with highest average farmer's debt were: Kerala (Rs 2,13,600), Andhra Pradesh (Rs 1,23,400), Punjab (Rs 1,19,500) and Tamil Nadu (Rs 1,15,900).

In five years between 2015 and 2019, 55,266 farmers have committed suicide, according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Prof. Chand wrote (in a 2017 paper) that low-level of absolute income and the large and deteriorating disparity between the income of a farmer and non-agricultural worker was one of the reasons for agrarian distress and also for "a sharp increase in the number of farmers' suicides" during 1995 to 2004 (For more read "Rebooting Economy 56: Why India should follow agricultural development-led industrialisation growth model ")

The idea of government

The 1991 liberalisation brought free-market and other neoliberal concepts, forever changing the idea of government (or state).

This change is best reflected in the language used by public servants and economists.

Food assistance to the poor or distressed/destitute is described as "food subsidy". Monetary support given to farmers for urea (but not other fertilisers and given to fertiliser companies, not farmers) is called "fertiliser subsidy". When farmers borrow money from banks it is called "loan" and when distressed farmers are let off from repaying their loans it is called "loan waiver".

The language changes when it involves private companies.

Tax assistance (tax cuts, tax holidays) to private companies is called "stimulus" or "'revenue impact of tax incentives" (before 2014, this was called "revenue foregone"). When private businesses default on their loans, it is called "non-performing assets" (NPA) of banks or "stressed assets" of banks. When these loan defaults are let off, which is routine and annual, it is called "write-off" of NPAs. Then banks are compensated for this loss with public money and called "recapitalisation" or "remonetisation" of banks. Further, the identities of defaulting private companies are zealously guarded by both the RBI and central government.

Notice how the first set of words and phrases suggest benevolence (or charity) on part of the government (towards ordinary citizens), while the second set conveys a sense of duty and responsibility of government (towards private businesses).

It is often forgotten that a government is elected by the people for their own welfare, not to serve private interests and surely not a few private interests.

The protesting farmers are victims of this change in the idea of government (or state).

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 50: Economic reforms for whom and for what?

No comments:

Post a Comment