Multiple global studies show air pollution increases death rates from COVID-19 and other respiratory diseases, while destruction of forests and wildlife habitats unleashes more such diseases from animals to humans

Prasanna Mohanty | July 9, 2020 | Updated 22:48 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | July 9, 2020 | Updated 22:48 IST

Air pollution not only makes humans more vulnerable to COVID-19 but also helps in spreading the virus and other microbial elements causing diseases through the air

The COVID-19 pandemic, which claimed 5.47 lakh lives globally as of July 8 and is expected to shrink worldwide economic growth by 5.2% in 2020, costing global economy $9 trillion over the next two years, is a perfect example of how undermining the environment has a huge cost.

Studies show that air pollution makes people more vulnerable to COVID-19 disease and deforestation increases human-animal conflicts spreading zoonotic diseases like it to pandemic proportions.

Here are a few eye-opening findings.

Higher air pollution led to higher COVID-19 deaths in US

A Harvard study of more than 3,000 counties in the US, representing 98% of the population, found that a small increase in long-term exposure to air pollution (exposure to particulate matter PM2.5) leads to "a large increase COVID-19 death rate".

It noted that a single-unit increase in air pollution (by 1 microgram/m3) in PM2.5 increased death rates by 8%, after adjusting for socioeconomic, demographic, weather, behavioural, epidemic stage, and healthcare-related confounders (variables).

Dr. Francesca Dominici, a professor of biostatistics at the Harvard who led the study, has been quoted as saying: "This study provides evidence that countries that have more polluted air will experience higher risks of death for COVID-19."

The Harvard study points out that the link between exposure to PM2.5 and disease is well known. Short-term exposure leads to higher hospitalisation rate for influenza, pneumonia, and acute lower respiratory infections. Long-term air pollution exposures "tend to be stronger" on chronic disease outcomes.

That is why the Harvard researchers asked the US to impose air pollution regulations. The US President Donald Trump suspended enforcement of pollution laws on March 26 and allowed companies to break those during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Not just that, on July 7, 2020, The Guardian ran an investigative report: "Over 5,600 fossil fuel companies have taken at least $3bn in US COVID-19 aid". These companies included oil and gas drillers and coal mine operators, as per the data released by the Small Business Administration (SBA) under the US government.

The report further said, "The $3 billion is probably far less than the companies actually received. The SBA did not disclose the specific amounts of loans and instead listed ranges. On the high end, fossil fuel companies could have received up to $6.7billion."

Higher air pollution leads to higher SARS and H1N1 mortality

The Harvard study pointed out past studies on the H1N1 pandemic: "Studies found particulate matter exposure to be associated with mortality during the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009. Recent studies have even used historic data to show a relationship between air pollution from coal-burning and mortality in the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic."

In 2003, during the time of the SARS outbreak in China, a US-China study, 'Air pollution and case fatality of SARS in the People's Republic of China: An Ecologic Study', found the areas with high and moderate long-term air pollution index (API) had higher SARS fatality rates at 126% and 71%, respectively, compared to areas with low API.

The index measures the concentration of particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, and ground-level ozone. In India, it is named the air quality index (AQI).

Why are studies on the impact of air pollution on H1N1 and SARS episodes relevant to COVID-19?

The WHO says, the H1N1 virus that caused the 2009 pandemic originated from animal (swine) influenza virus that causes respiratory illness and is closely related to the COVID-19 virus. The SARS virus is called SARS-CoV and the COVID-19 virus SARS-CoV-2. Both viruses are suspected to have come from bats. SARS here stands for "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome".

Polluted northern Italy saw higher death rate from COVID-19

Another study on COVID-19 in Italy in March this year, 'Can atmospheric pollution be considered a co-factor in extremely high level of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy?', looked at the air pollution and COVID-19 deaths. Results published on March 24, 2020, found that the death rate reported in northern Italy was 12%, compared to 4.5% in the rest of Italy.

Northern Italy is one of Europe's most polluted areas.

The study explained how air pollution makes people vulnerable to COVID-19: "In conclusion, it is well known that pollution impairs the first line of defense of upper airways, namely cilia, thus a subject living in an area with high levels of pollutants is more prone to developing chronic respiratory conditions and suitable for any infective agent. Moreover, as we previously pointed out, a prolonged exposure to air pollution leads to a chronic inflammatory stimulus, even in young and healthy subjects."

Air pollution spreads COVID-19 through air

Air pollution not only makes humans more vulnerable to COVID-19 but also helps in spreading the virus and other microbial elements causing diseases through the air.

A 2004 study in China found that the large community outbreak of SARS, a coronavirus closely related to the one causing COVID-19, was because of airborne transmission.

That is, the polluting particulate matter in the air (PM2.5 and PM10) carried and spread the SARS virus.

There are more such studies.

One of those collected airborne PM2.5 and PM10 in Beijing over a period of 6 months in 2012 and 2013, including those from several historically severe smog events. It showed airborne particulate matter "accommodates rich and dynamic microbial communities, including a range of microbial elements (including bacteria and viruses) that are associated with potential health consequences".

On July 6 this year, 239 scientists from 32 countries wrote a letter, 'It is Time to Address Airborne Transmission of COVID-19', to the WHO saying that increasing evidence shows the coronavirus is airborne.

They wrote: "There is significant potential for inhalation exposure to viruses in microscopic respiratory droplets (micro-droplets) at short to medium distances (up to several meters, or room scale), and we are advocating for the use of preventive measures to mitigate this route of airborne transmission."

That is because the WHO says: "According to current evidence, the COVID-19 virus is primarily transmitted between people through respiratory droplets (droplet particles of >5-10 micro-metre in diameter) and contact routes. In an analysis of 75,465 COVID-19 cases in China, airborne transmission was not reported."

Respiratory droplets are more than 5-10 micro-metre in size. PM2.5 and PM10 are particulate matters of size 2.5 micro-metre or less and 10 micro-metre or less, respectively.

This is why these scientists asked the WHO to change its strategy to tackle COVID-19.

Deforestation spreading disease from animals to humans

There is another aspect to the environmental impact on COVID-19: transmission of diseases from animals to humans, called zoonotic diseases, as COVID-19 is suspected to be.

On July 6, 2020, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) released a report. prepared by multiple universities, research institutions and multilateral agencies saying that zoonotic diseases are increasing and will continue to do so unless corrective measures are taken to improve ecosystems, prevent destruction of wildlife habitats and reduce climate change.

It says 60% of known infectious diseases in humans and 75% of all emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic, and that there have been at least six major outbreaks of novel coronaviruses in the last 100 years, all of which imposed high costs across several continents.

Ebola (bats), MERS (probably bats), SARS (bats), Zika (primates) virus and bird flu (wild waterfowl) all came to humans from animals. The SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 has "probably" come from bats. The only other time the WHO had declared a pandemic was in 2009 when H1N1 flue, found to have originated in pigs, spread.

The UNEP report says deforestation and fragmentation of ecosystems and wildlife habitats increase human-wildlife contact and conflict, leading to the spread of zoonotic diseases.

A WHO paper says most emerging infectious diseases, and almost all recent pandemics, originate in wildlife, and there is evidence that increasing human pressure on the natural environment may drive disease emergence. It, therefore, calls for greater protection of biodiversity and natural environment to reduce the risk of future outbreaks of other new diseases.

Climate change aiding COVID-19 spread

The UNEP report of July 6, 2020, also pointed at how climate change (global warming) is adding to the spread of COVID-19 and other zoonotic diseases.

It says, "Many zoonoses (zoonotic diseases) are climate-sensitive and a number of them will thrive in a warmer, wetter, more disaster-prone world foreseen in future scenarios", adding that there is some speculation that the COVID-2 virus (SARS-CoV-2) may survive better in cooler, drier conditions when outside the body.

The executive director of UNEP, Inger Andersen, writes in the foreword of the report: "The drivers of pandemics are often also the drivers of climate change and biodiversity loss - two long-term challenges that have not gone away during the pandemic."

In the meanwhile, the news of bubonic plague break out in China has hit the headlines.

The UNEP report mentions that originally the bubonic plague came from animal to human but had subsequently transmitted mainly from human to human. It goes on to add: "The true zoonotic bubonic plague or pest (Black Death caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis) of the mid-fourteenth century killed millions in Eurasia and North Africa, wiping out a third of Europe's population".

Now here is some good news.

Before that, here is a brief backgrounder. "Climate change skeptics" or "climate change denialism" that was fostered in the US that later spread to rest of the world, undermine the impact of global warming and climate change and their devastating impact on lives and economies.

This is the handiwork of polluting industries seeking to evade and avoid paying for the huge social and environmental costs their operations impose. (For more read 'Deconstructing Neoliberalism II: How neoliberal ideas can wreak havoc on economies ')

As a result the "polluter pays" principle has been turned on its head. While polluting industries profiteer, social and environmental costs are borne by people, communities, and governments using taxpayers' money (for healthcare and other costs). The US government even bails them out with taxpayers' money as The Guardian's investigative report mentioned earlier reveals.

Environmental pollution leads to illness, incapacitates, reduces the ability of millions to earn their livelihood, and causes millions of deaths. Air pollution alone causes 7 million deaths globally every year, a study published in the medical journal Lancet in July 2019 shows. (For more read 'Unravelling GDP growth II: Why GDP measures output, not people's well-being ' for more).

Deforestation for mining of coal and other minerals and industrial activities leads to loss of livelihood of millions of tribals and other communities that depend on it.

COVID-19 crashes global carbon emissions

The good news is that the COVID-19 induced shutdown of polluting industries and activities (oil, gas and coal operations, vehicular traffic, etc.) have drastically reduced energy demand and carbon dioxide emissions that cause global warming.

Various studies estimate the reduction variously.

The Global Carbon Project (GCP), a global body of scientists set up in 2001, projects the fall in carbon dioxide emissions in the range of (-) 4 to (-) 7%, from the mean level of 2019.

The title of the study, 'Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement', makes it clear that it is a temporary change.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), a multinational body set up in 1974, the decline would be by (-) 8% from the 2019 level.

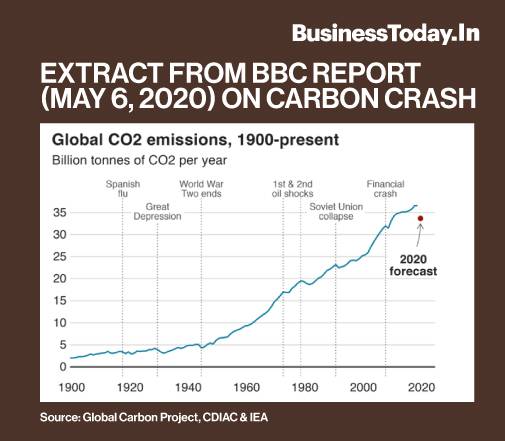

The BBC combined these data with that of the Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Centre (CDIAC) of the US Department of Energy (DOE) to map carbon dioxide emissions (in billion tons) since 1990.

The map is reproduced below.

The map is all the more interesting because it traces the impact of several major events in the past 120 years, starting with the Spanish flue of 1918 to 2019 Great Depression, World War I & II, oil shocks of the 1970s, 2007-08 Great Recession to the COVID-19 shutdown. It says the current one is the "biggest carbon crash" of all.

For India, the Global Carbon Project (GCP) data shows how carbon dioxide emissions (median value) have fallen from January 1 to June 11, 2020.

A 2018 UN panel on climate change warned that if carbon emissions are not reduced to keep global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level by 2030, many of the catastrophic events foreseen at 2 degrees Celsius rise would be unleashed with catastrophic consequences.

For that to happen by 2030, carbon dioxide emissions would have to fall by about 45% from the 2010 level, which was about 32 billion tons per day.