While government claims on tax compliance and GST collections paint a healthier picture of the economy, tax-to-GDP has fallen for three consecutive years and tax collections across the board in the first half of FY21 are nowhere close to FY20, indicating that trouble is far from over

Prasanna Mohanty | November 26, 2020 | Updated 15:35 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | November 26, 2020 | Updated 15:35 IST

Two significant news regarding tax collections came this month to assure Indians that the economy is headed for recovery: (i) demonetisation has improved tax-to-GDP ratio and tax compliance and (ii) GST collection crossed Rs 1 lakh crore-mark in October 2020.

The first one came on November 8, 2020, through a series of tweets by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, which was also released by the Press Information Bureau (PIB), and Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman. The claims accompanied a series of graphs showing all-round improvement without, however, revealing the underlying assumptions and statistics.

The PIB statement and the accompanying tweet of the Prime Minister made several claims about the demonetisation of 2016: (a) "tax/GDP ratio drastically improved" (b) "made India a lesser cash-based economy" (c) "helped reduce black money, increase tax compliance", gave a "boost to transparency" and concluded that the demonetisation (d) has been "greatly beneficial towards national progress".

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 47: Do India's fiscal numbers suggest a quick turn-around?

Had the official databases of the Controller General of Accounts (CGA) and RBI been checked, such claims would not have been made.

Tax-to-GDP ratio is slipping for three years

The following graph maps tax-to-GDP ratio by using the CGA data on gross tax collection and the RBI's GDP numbers at market price since FY05.

Tax-to-GDP ratio reflects tax compliance and also the central government's ability to finance its expenditures and hence, is critical to determine the health of the economy.

The last three fiscals' tax-to-GDP ratios were confirmed by the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) in June 2020 and widely covered by the media which confirmed that the ratio had indeed plunged to 9.88% in FY20, from 10.97% in FY19 and 11.22% in FY18 due to poor health of the economy.

Notice how the tax-to-GDP ratios take a plunge immediately after the demonetisation in FY17 and the GST in FY18. Like demonetisation, GST was also touted as a move which would improve tax-to-GDP ratios with the Niti Aayog's estimates predicting a jump from 17% in FY16 to 22% in FY23 (central and state taxes taken together) in its "Strategy for New India@75", released in November 2018.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 45: What is AatmaNirbhar Bharat and where will it take India?

The demonetisation and GST were the twin shocks that derailed the Indian economy. Demonetisation sucked out 86% of high-value cash in circulation in an instant on November 8, 2016 (demonetised at four-hour notice). Cash was rationed and people queued up daily outside banks for about six months to run daily expenses. More than 100 people died in these queues, millions lost jobs and other livelihood sources and it devastated the informal economy but these were never tracked or studied by the central government.

Before the people and economy could recover, there came GST at a mid-night session of Parliament of June 30-July 1, 2017, billed as "the second freedom movement" only to be postponed for two months the very next morning. (For more, read "Rebooting Economy 46: Who is designing India's growth path? ")

India is far more cash-based economy now, not less

The claim that demonetisation made India a less cash-based economy is contrary to official data.

The following graph maps the RBI's weekly currency-in-circulation (CiC) data from November 4, 2016 - 4 days before the demonetisation - to November 6, 2020.

On November 4, 2016, CiC stood at Rs 17.98 lakh crore which climbed up progressively to Rs 27.3 lakh crore on November 6, 2020 - a rise by 51.7%.

A "cashless" economy became the new objective of demonetisation once the central government realised its three stated goal posts - eliminate black money, terror funding and counterfeit notes - werenon sequitur.

Now that India is progressively becoming a far more cash-based economy, black money in circulation should also be going up - going by the fundamental logic of demonetisation. That, however, wasn't the case then nor now (real estate, gold , and financial instruments involve black money).

In 2012, the finance ministry brought out a white paper on black money ("Measures to Tackle Black Money in India and Abroad"). It listed the methods and most prone sectors generating black money in which "cash and use of counterfeit currency" (target of demonetisation) came at No. 6.

The first five were: (i) suppression of receipts, inflation of expenditure by businesses (ii) land and real estate transactions (iii) corruption by government officials (iv) financial market transactions and (v) bullion and jewellery transactions. After "cash and counterfeit currency" were three more: (vii) trade-based money laundering (viii) non-profit organisations (NPOs) and (ix) participatory notes.

The world was so horrified by demonetisation that Gita Gopinath, chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned other countries against following this and explained to a television channel that no macro-economist would recommend demonetisation to any developing or advanced economy.

She later published a paper in 2018 (co-authored by economists from Harvard University and RBI, among others) showing India's GDP shrunk by 2 percentage points that quarter due to the cash shortage (Q4 of FY17).

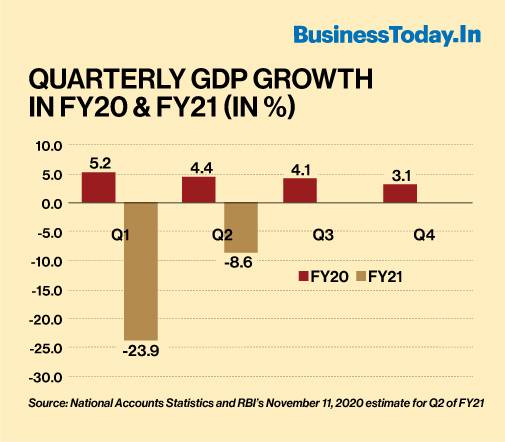

Former Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian pointed out in 2018 that this"massive, draconian, monetary shock" plunged GDP for the next 7 quarters - from an average growth of 8% in pre-demonetisation quarters to 6.8% in subsequent seven quarters. Since the GDP data has been fudged multiple times, these changes can't be seen in the GDP data now. (To know how this happened, read "Rebooting Economy XXV: How a series of economic misadventures derailed India's growth story ")

The RBI's Occasional Papers ("Modelling and Forecasting Currency Demand in India: A Heterodox Approach"), published on July 16, 2020, says the post-demonetisation years (FY18, FY19 and FY20) saw an "extraordinary jump" in CiC.

It said only thrice India had witnessed more than 17% surge in CiC for three or four consecutive years until then in the past 50 years. The relevant table is reproduced below.

Ironically, the post-demonetisation CiC surge happened when nominal GDP grew at less than 10% growth, while other three occasions had seen 14.7% to 16.6% growth - indicating it wasn't growth (leading to inflation) that caused it, but it happened "largely on account of remonetisation of the economy after the withdrawal of high-value banknotes (demonetisation) on November 8, 2016".

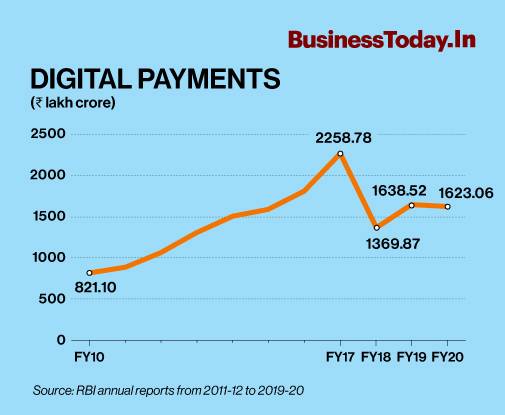

Digital payment falling post-demonetisation

The demonetisation's shifted goalpost (cashless economy) pushed digital payments without citing evidence or explaining the rationale. Whims and fancies reigned high in the policy and planning arena then.

It was supposed to check black money generating transactions and bring transparency. But the contrary has happened - India's digital payment fell drastically post-demonetisation - as the following graph shows.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 43: States exhaust MGNREGS fund, leave Rs 1,386 crore in unpaid wages

The graph plots "total digital payments" since FY10 from the RBI's annual reports (FY12 to FY20). "Total digital payments" include five payment systems/methods: RTGS, credit transfers, debit transfers, card payments, and prepaid payment instruments.

Total digital payments were fast improving until demonetisation derailed those. From Rs 2,258.78 lakh crore in FY17, total digital payments fell to Rs 1,369.87 lakh crore in FY17, recovered to Rs 1,638.5 lakh crore in FY19, and then fell to Rs 1,623.1 lakh crore in FY20.

It is more likely to fall further in FY21.

Has tax compliance improved?

The PIB's November 8, 2020 statement and tweets made therein claimed improvement in tax compliance (i) "self-assessment tax of more than Rs 13,000 crore was paid by targeted non-filers" (ii) 3.04 lakh persons who deposited cash of Rs 10 lakh or more but had not filed IT returns were "identified" and (iii) 2.9 lakh such identified non-filers responded and paid a self-assessment tax of Rs 6,531 crore.

None of this requires demonetisation.

Firstly, these are routine exercises carried out by Income Tax officials.

The officials have been identifying millions of non-filers and "dropped filers" (those who stop filing returns) through the age-old Non-filers Monitoring System (NMS) that tracksannual information returns (AIRs), centralised information branch (CIB) data, and TDS/TCS statements. (For more read "Taxing the untaxed III: Is govt oblivious to leakages in direct tax collection? ")

That the NMS was fully operational much before the demonetisation is evident in the third report of the Tax Administration Reform Commission (TARC) released in 2014.

The third TARC report said the NMS had identified2.2 millionnon-filers with potential tax liabilities in 2014 - up from0.2 millionin 2013. The relevant part is reproduced below.

The real problem is the efficacy of the NMS - what happens next. There is no data or information to show what happened in those millions of cases. Going by the falling tax-to-GDP ratio, it is evident that the NMS hasn't worked. (For more read "Rebooting Economy XXVII: Fiscal mismanagement threatens India's economic recovery ")

As for improvement in self-assessment tax, the then Finance Minister Arun Jaitley had nailed the futility of it in his 2018 budget speech. He said the presumptive income scheme (PIS), which allows taxpayers to choose a pre-determined tax slab on their own and pay tax accordingly without having to maintain formal tax records.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 42: How will changes to land laws in Jammu and Kashmir help, and whom?

Jaitley further said: "Under this scheme, 41% more returns were filed during this year which shows that many more persons are joining the tax net under simplified scheme. However, the turnover shown is still not encouraging".

That is not surprising. Tax officials have known it all along. Entrepreneurs and traders take advantage of this scheme to switch to lower tax slabs.

On September 19, 2020, Minister of State for Finance Anurag Thakur confirmed to the Lok Sabha how very few, only about 1% of Indians, pay tax.

In a written reply to a question, Thakur said: "Yes, approximately, for Financial Year 2018-19 till Feb.2020, 5.78 Crore Returns of Income were filed by individual taxpayers out of which1.46 Crore individual taxpayers filed Returns declaring income above Rs. 5 Lakh." (Finance Act of 2019 provides that individual taxpayers with income of up to Rs 5 lakh are not required to pay any income tax from Assessment Year 2020-21 onwards.)

No such data is available in the public domain to map the trend. Furthermore, whatever tax data are released, have not been updated after FY19.

Drastic fall in GST and other tax collections in first half of FY21

The second good news on tax front came on November 1, 2020.

The finance ministry released a statement through the PIB saying that the gross GST collection for October 2020 stood at Rs 1,05,155 crore - 10% higher than the corresponding month in FY20. Of this, Central GST accounted for Rs 19,193 crore, State GST Rs 25,411 crore, Integrated GST Rs 52, 540 and Cess Rs 8,011 crore.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 41: India's growing poverty and hunger nobody talks about

Now, such statements are issued only when the gross GST collection touches the Rs 1 lakh crore mark, not otherwise. Hence, there is no way of mapping the trend. The last occasions when such statements were issued, were: January and February of 2020 and November and December of 2019.

All those were part of FY20, none from FY21. This means, in FY21, the gross GST touched the 1 lakh crore mark for the first time in Q3 (October 2020).

The CGA provides some of these data for the first half (H1) of FY21, mapped below for comparison with FY20.

On every single count (corporate tax, income tax, various GST components, and gross tax collections), the FY21 numbers have slipped from FY20, except for IGST.

Taken together, the claims on the beneficial effects of demonetisation and higher GST collections, made in November 2020, present a rather misleading picture of the state of the economy.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 40: Why Punjab farmers burn stubble?