Not just in health emergencies, even in normal times, India needs a public healthcare system that can ensure that "catastrophic" healthcare expenditure does not routinely drive six crore Indians into poverty every year

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: April 17, 2020 | 01:09 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: April 17, 2020 | 01:09 IST

India has one of the world's highest out-of-pocket (OOP), 65% of total healthcare expenditure, due to poor public expenditure on healthcare

While India grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic, it may come as a big shock to many that the Indian government is very much aware that (a) healthcare entails "catastrophic expenditure" and that (b) it "pushes nearly six crore (60 million) Indians into poverty each year".

These assertions come from India's flagship healthcare programme Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) describing normal times, not health emergencies.

It should then come as a far bigger shock that the Indian government launched the "world's largest health insurance/assurance scheme", which is how the PM-JAY officially describes it, based on a model that has not only not prevented "catastrophic expenditure" in its home soil, it rather added to it.

Everyone who should know already knew this too.

This is because the PM-JAY is modelled on the failed Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) of 2008. The RSBY provided insurance cover for up to Rs 30,000 towards hospitalisation for BPL families. The PM-JAY of 2018 provides hospitalisation cover of up to Rs 5 lakh to the bottom 40% of the population through an insurance scheme. It is entirely funded by taxpayers' money with the centre and states sharing their burden at 60:40.

Several things are wrong with this system.

(i) PM-JAY: Addresses the wrong end of problem

For one, the "catastrophic expenditure" on healthcare is not so much because of high hospitalisation expenditure but a far costlier outpatient or OPD care. This too is widely known but bears repetition.

Here are two credible studies for illustration.

One is a 2014 study based on the NSSO's consumer expenditure surveys of 1999-2000, 2004-05 and 2011-12. A group of national and international health experts analysed the survey data and concluded that out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure (a) on hospitalisation (inpatient care) accounted for, an average of, 1.3-2.36% of total household expenditures in rural areas and 1.31-1.86% in urban areas. (b) but the same for outpatient care (OPD) accounted for 4.74-5.37% in rural areas and 3.6-3.89% in urban areas.

This means, on average, the OPD expenditure is more than double the cost of hospitalisation (inpatient). The graph below takes the averages for rural and urban areas across the three survey periods.

India has one of the world's highest OOP, 65% of total healthcare expenditure, due to poor public expenditure on healthcare.

Since then, the NSSO's 75th round of consumer expenditure survey on health for 2017-18 was released in November 2019 but until its unit-level data is analysed by academics, the percentages of household expenditure on OPD and hospitalisation would not be known. The NSSO reports don't provide such information.

However, Dr Sakthivel Selvaraj of the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), who was a part of the above study, says the situation is unlikely to have changed since nothing dramatic happened in the intervening period.

The PM-JAY was launched in September 2018 by when the NSSO's 2017-18 survey, which was carried out between July 2017 and June 2018, was over.

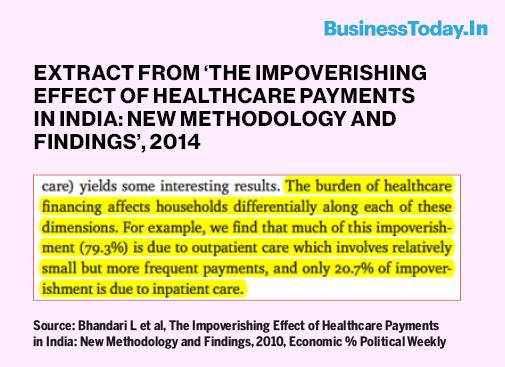

The other study, published in the Economic & Political Weekly arrived at similar conclusions by using the NSSO's healthcare survey of 2004 data (Morbidity, Health Care and the Condition of the Aged). It quantified catastrophic "burden" of healthcare expenditure.

It said the outpatient (OPD) care burden on impoverishment was 79.3% as against only 20.7% due to inpatient care (hospitalisation).

The study further said, "Around 1.3% of total households (1.3% in rural areas and 1.2% in urban areas) fell below poverty line (BPL) as a result of the expenditure on inpatient care, while 4.9% of households (5.3% in rural areas and 3.8% in urban areas) fell BPL as a result of outpatient care. That non-hospital expenditure has greater impoverishing effect than expenditure on hospitalisation which is also reported in other countries."

So, what knowledge, experience or insight led to designing the world's largest healthcare programme around just hospitalisation?

(ii) RSBY: A failed model

The PM-JAY is an expanded version of the RSBY of 2008 and has now been merged with it.

Several studies have found glaring failures of the RSBY.

One 2018 study by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) concluded that "there is no evidence that it caused a reduction in out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure" and that the dominating presence of for-profit private healthcare providers "failed to address the issue of access and financial risk protection".

Another 2018 study by TISS-OP Jindal Global University said not only did it not eliminate the OOP, but the insured patients going to private providers also ended up paying, on average, Rs 17,741 from their pocket.

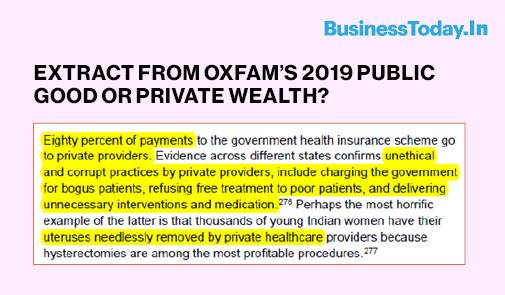

A third study, of 2019 by the Oxfam International said the powerful private health corporations escalated the cost of premiums three-and-half times in some states and threatened to withdraw services if governments did not comply.

They indulged in unethical and corrupt practices most notable being the needless removal of uteruses (hysterectomy) of thousands of young women (like tribal women of Telangana) as such procedures are among the most profitable.

Also Read:Coronavirus Lockdown III: Is India's public healthcare system prepared to fight the COVID-19 menace?

It said 80% of all insurance payments went to private providers.

All this makes it clear that the healthcare scheme fully funded by taxpayers' money was channelised into private hands, instead of building public healthcare.

(iii) PM-JAY: Mimicking RSBY behaviour

Jan Sawsthya Abhiyan (JSA), a non-government healthcare watchdog working across the country, finds disturbing similarities between the RSBY and PM-JAY.

Here are three such examples.

One, 2018-19 annual report of the PM-JAY scheme shows that patients continue to pay from their pockets for healthcare even when it is a cashless programme, fully paid by the government and aimed at eliminating OOP that drives 60 million Indians into poverty every year.

A segment marked "grievance redressal" says 93% of complaints are about "money collected". What is "money collected" has not been explained and quite predictably, what steps have been taken to redress it find no mention. How much such money has been collected too finds no mention.

But those familiar with the ground realities know what it is.

Sulakshana Nandi, public health researcher and JSA's national coordinator, says since healthcare providers under the PM-JAY are not supposed to ask for any money from patients, complaints of "money collected" means that patients are being asked to pay money.

Clearly, this money is over and above the "claims" that healthcare providers make and directly paid for by the central and state governments (at 60:40).

Nandi explains, "The reason people incur OOP expenses is because hospitals are taking additional money from them illegally, on some pretext or other. That is the reason the OOP continues, from the RSBY days to now the PM-JAY."

The second pattern relates to high number of hysterectomy operations being carried out by private healthcare.

Patterns of utilisation for Hysterectomy: An analysis of early trends from Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY), another document of the National Health Authority (NHA), says "more than two-thirds (68.7%) of all claims for hysterectomy were in the private sector under PM-JAY". The total number of claims in the first year of PM-JAY was 21,896.

This calls for a probe to ensure that vulnerable women, especially tribal women, are not burdened with a procedure (like under the RSBY) they might not need, which might be crippling or life-threatening for them, just for making profit.

The third pattern is that most of the taxpayers' money is again going to private healthcare.

Raising the Bar: Analysis of PM-JAY High-Value Chains, another NHA document, shows (i) 66% of all money claims (ii) 76% of high-value claims (above Rs 30,000) and (iii) 81% of very high-value claim (above Rs 1 lakh) are going to private healthcare.

Three questions arise from these patterns.

- Who would build a quality healthcare which is affordable to India's vast majority of low-income people if the public money is ploughed into private hands?

- How would the healthcare expenditure stop being catastrophic or cease to push 60 million Indians into poverty every year ever?

- "How long can the Indian economy sustain paying for vastly expensive private healthcare without going bankrupt?

PM-JAY: End of the road for public healthcare?

Business Today has detailed how the entire focus of the PM-JAY is to build and promote private healthcare with public money and other resources.

In January 2019, Health Ministry asked the state governments to provide land and 40% viability gap funding (VGF) to private healthcare under the PM-JAY. In January 2020, government think tank Niti Aayog revived another failed and abandoned development model, Public-Private Participation (PPP), to ask the state governments to handover district public hospitals to private players.

In the February 2020 budget speech, the Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman pitched for the VGF to states "fully" cooperating in handing over the public district hospitals to private healthcare providers.

This is shocking behaviour, especially in view of the more recent official data.

Private healthcare cost a bomb

The NSSO's 2017-18 consumer survey (health) report, released in November 2019, shows hospitalisation expenditure, which is what PM-JAY provides for, six to eight times higher in private healthcare than public healthcare.

The graph below presents the average cost of hospitalisation in rural and urban areas, for both public and private healthcare, which is self-explanatory.

A break-up of hospitalisation expenses show that every single component of healthcare cost is more in private care.

What these graphs and the experience with the RSBY demonstrate is that (i) Indian state bears a higher burden by "purchasing" (which is what the National Health Policy of 2017 calls it) private healthcare (ii) private healthcare cost would keep rising and (iii) bottom 40% of the population would remain at the mercy of private healthcare forever if public money is not used to build public healthcare.

Is private healthcare more efficient?

Here is an eye-opener for those who think private healthcare is intrinsically and necessarily more efficient than public healthcare.

Comparative Performance of Private and Public Healthcare Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review, a study carried out by several top-grade medical institutions in the world (the US and UK) and published in 2012, concluded the following:

Is insurance-based model (PM-JAY) the right choice?

Business Today reached out to two eminent and globally well-regarded public health experts for their views on the insurance-based healthcare model--PM-JAY, especially at the time of health emergency.

Dr. T Sundararaman, former director of National Health Systems Resource Centre, GOI (2007-14), the apex technical support institute for the National Healthcare Mission (NHM) says, "Insurance-based model assumes a lot of secondary and tertiary care is best purchased from private providers through market-like arrangement. However, when it comes to public health emergency, market ceases to function and one requires pre-eminent role of the government in providing even advanced tertiary care."

He adds that "if all our district hospitals had ICUs and were using ventilators then purchase of additional ventilators would have been adequate. But even the skill of supporting system for providing ICU care has to be put in place which can't be done overnight. Lack of expansion of public services has meant that they have been designed to deliver minimum package of services. But a pandemic like this is a maximal event."

"The private sector healthcare, even though empanelled, can't be prevented from denying healthcare to the needy or even from charging exorbitant rate. There have been reports of many private providers cutting back or even closing down. In fact, what seems to work now is placing private hospital or part of it under public authority in India and abroad, a sort of transient nationalisation," he states.

Dr Sakthivel Selvaraj of the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) says, "in terms of access to hospitalisation services government-funded insurance model may improve it but may not provide financial risk protection for several reasons. One is that two-thirds of out-of-pocket expenses are on account of OPD care within which medicines cost the most and two, the entire service under the insurance-based model is hospitalisation. So, insurance cover may not reduce financial burden of OOP."

He further states, "we have seen this in the last 15 years. Despite RSBY and PM-JAY, OOP expenses have not been reduced. Paying for private healthcare from public money is highly inefficient (private healthcare cost is many times that of public healthcare) while strengthening public sector with public money is more efficient."

Here is what an article published in The Lancet in August 2019 says about it.

It says India's publicly funded health insurance has neither led to equity nor provided protection to the vulnerable, rather reinforced health inequities by ploughing taxpayers' money to for-profit private care.

Going forward

What it means to rely on private healthcare at the time of COVID-19 is well-known. Here is the latest addition. On April 9, 2020, the Supreme Court asked private labs to provide free testing for COVID-19. What was the response?

Leading private labs immediately demanded to know who would bear the cost. Another one suspended testing right away until further clarity (on payment). A prominent entrepreneur who happens to be a prominent public intellectual now joined in saying that this SC order would adversely impact COVID-19 testing in India and private labs can't simply be asked to run their businesses on credit.

It may be recalled that when the Indian government sought private help in COVID-19 tests, it immediately fixed an upper limit for costs at Rs 4,500 to prevent private healthcare providers from exploiting patients.

If the Indian government learns the right lessons from the experience with its health policy, not only the concerns of catastrophic healthcare expenditure pushing 60 million Indians into poverty every year can be stopped, but there is a big 'if'.

No comments:

Post a Comment