Getting the basics right holds the key. This would involve first acknowledging that a large population has lost incomes, savings and jobs and second, consumption drives the economic growth which had already been weakened even before the pandemic hit

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: April 24, 2020 | 00:00 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: April 24, 2020 | 00:00 IST

Demand is generated through consumption which calls for cash in the hands of a majority of people, not a few

While policymakers are busy figuring out how to exit the lockdown and kick-start the economy, here are a few quick policy tweaks and improvement in governance that can go a long way in setting the tone.

Step 1: Food supply and cash transfers to vulnerable

The first priority is to ensure that people don't starve or are deprived of basic necessities for survival due to job losses and a complete lockdown in economic activities. Starvation deaths have begun and long queues and long trekking for food in Delhi, Chandigarh, Patna, Badaun and elsewhere nearly a month after the lockdown began show gross failure of governance.

Hungry and enfeebled workers don't kick-start economy.

The impact is particularly harsh on a vast majority of people, the landless, small and marginal farmers, urban migrant workers, petty shopkeepers, barbers, tailors, traders etc. constituting about 93% of the total workforce of India engaged in the informal economy. Apart from loss of income, they would surely have run out of savings by the time the lockdown is lifted.

Notwithstanding the Supreme Court's reluctance to step in for the migrant workers (it reportedly wondered why they need wages if meals are being given), cash in their hands is essential for survival. They need cash to feed dependents back home, buy medicines (including for COVID-19 treatment), pay room or house rents and also for many daily essentials. Ensuring a dignified life to people is a constitutional obligation of both the Supreme Court and the central and state governments.

Cash transfers to bottom 40% population: Rs 62,820 crore

Poor demand won't kick-start economy either.

The Keynes prescription for the Great Depression of 1929 that aggregate demand--total household, businesses and government spending--is the most important driving force of an economy, holds true even now.

Demand is generated through consumption which calls for cash in the hands of a majority of people, not a few. Demand had weakened even before the COVID-19 hit. If demand for non-food items is not revived, there is little reason for industries and services to open their shops.

Fortunately, food availability is not a concern (FCI godowns had 58.5 million ton of rice and wheat in March 2020 and rabi harvesting would add further cushion it), its access is.

Fortunately too, the PM-JAY or Aysuhman Bharat scheme has already prepared the ground since it was launched in September 2018, covering the bottom 40% of India's population, or 10.47 crore (104.7 million) families. They can now be quickly reached through direct cash transfers.

How much money is needed to assist them is a matter of debate. Assuming each family is given Rs 1,000 per month (same amount that Bihar has transferred to migrants stuck outside), it would cost Rs 10,470 crore. For six months (or Rs 6,000), the cost would be Rs 62,820 crore.

This could be a starting point. Far more families would have been hit by the lockdown. Piyush Goyal, the minister for railways and commerce, was right when he said, "The poor have the first right on the resources of the nation", while presenting the 2019 interim budget.

Can such sums be mobilised? Yes, but more of that later.

Step 2: Devolution of financial resources to states

State governments are at the frontline battling COVID-19.

The central government needs to assist them as much as possible. Since a lot of attention is being paid to tight fiscal situation, here are some easy ways to find the required funds.

Pending GST dues for FY20: Rs 69,006 crore

The first step the central government should take is to release the Goods and Services Tax (GST) dues to states.

On April 8, 2020, the central government released Rs 14,100 crore of pending dues for October-November 2019. The total dues for the two months were Rs 34,503 crore.

The dues for the next four months (December 2019 to March 2020) are pending too. This works out to be Rs 69,006 crore, taking Rs 34,503 as the bimonthly benchmark.

Allowing CSR donations to CM Relief Funds

In a step that defies logic and remains unexplained yet, the central government has allowed corporate entities to donate to the newly set up PM CARES fund to be treated as CSR spending while disallowed the same for CM Relief Funds.

This chokes a legitimate source of fund for states. The sooner it goes the better. Besides, it is also counter-intuitive to set up the PM CARES fund when the PM's National Relief Fund (PMNRF) exists (since 1950s) for the very same purpose.

PM CARES fund: Rs 6,500 crore

In the first week of April, newspaper reports said the PM CARES Fund received more than Rs 6,500 crore in donations. The fund is likely to grow fast, especially after the Jharkhand High Court asked a former MP and five others to pay Rs 35,000 each to this fund as a bail condition on April 16, 2020.

More donations mean more disposal fund to fight COVID-19.

Health emergency funds: Rs 15,000 crore

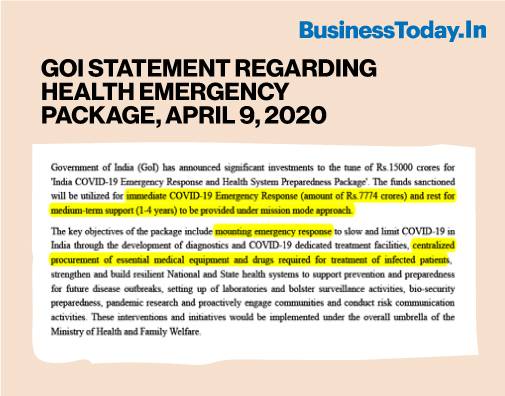

The central government recently announced an emergency health response package of Rs 15,000 crore. The details show that only Rs 7,700 crore is meant for the current fiscal and the rest (Rs 7,300 crore) for four years. Moreover, all "essential medical equipment and drugs" would be procured centrally.

This means states would get very little health emergency fund, if at all. Going by the central government's record so far, it makes more sense to hand over the money to state governments. In any case, why should India wait for four more years by which time COVID-19 may have disappeared after taking its toll?

Relaxing FRBM norms to allow higher borrowing by states

The Keynesian prescription of deficit financing without causing inflation is valid for the current situation. India has been going through both (a) demand depression and (b) high unemployment even before COVID-19 hit.

Therefore, the central government would do well to concede the demands of Kerala, Odisha and other states and relax the Fiscal Responsibility Business Management (FRBM) norms to borrow more.

Pending MGNREGS arrears and cut in allocations: Rs 16,570 crore

On March 27, 2020, the central government paid Rs 4,431 crore out of its total pending arrears of Rs 11,499 crore for the rural job guarantee scheme (MGNREGS) for FY20. This still leaves Rs 7,068 crore pending.

The budget allocation for FY21 has been cut down by Rs 9,502 crore--from Rs 71,002 crore in revised estimates for FY20 to Rs 61,500 crore in FY21.

Taken together, a further sum of Rs 16,570 crore should be front-loaded immediately for payment of unemployment allowance which the law provides (section 7(1) of the MGNREG Act of 2005) but never honoured. More so since the lockdown has cut down MGNREGS jobs to 1% of normal in April.

The other step the government should take is to raise the average days of work from a historical 40-45 days to 150, which is provided for emergencies like drought.

Pending PM-KISAN arrears: Rs 68,487 crore

The relief package of Rs 1.7 lakh crore announced on March 26 promised to "front-load" the first instalment (Rs 2,000) of PM-KISAN for FY21. Nothing can be further from the truth.

Last updated on April 14, 2020, the official website shows that the second instalment of FY20 was in progress. The number of farmers for which fund transfer order (FTO) had been issued stood at 87,411,223, up from 84,986,517 on April 6, 2020. An image of the progress, taken at 3 pm on April 20, 2020, is reproduced below.

The images show that the targeted beneficiaries are 144,999,999 but the first instalment for FY20 has been paid only to 92,562,816, a shortfall of 5.25 crore (52.5 million).

The third instalment for FY20 has not started yet, let alone frontloading the first one for FY21.

Assuming full payment to the intended beneficiaries, this would mean a payment of Rs 68,487 crore (Rs 10,487 crore of the pending first instalment beneficiaries and Rs 29,000 crore each of them in the third instalment of FY20 and the first instalment of FY21).

Under the scheme, the government transfers Rs 6,000 annually in three instalments to all farmers (cultivators).

Also Read:Coronavirus Lockdown III: Is India's public healthcare system prepared to fight the COVID-19 menace?

Extending PM-KISAN to landless: Rs 86,580 crore

The PM-KISAN assistance is not given to the most deserving and poorest of the poor--landless agricultural labourers who constitute 55% of the total agricultural workforce or 144.3 million, as per the Census 2011.

A cash transfer of Rs 6,000 a year to them would cost Rs 86,580 crore.

Preventing misallocations of PMJDY: Rs 1,000 crore

Last week, the state-owned Doordarshan News broadcast had tweeted a series of videos showing women thanking Prime Minister Narendra Modi for transferring Rs 500 to their accounts under the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) as part of the relief package.

The PMJDY was launched in 2014 for the unbanked poor to open zero-balance accounts for them for their financial inclusion. Going by the images of beneficiaries and their homes, it is difficult to believe that the money is indeed reaching those who did not have bank accounts until 2014.

If even 10% of such allocations is saved, this would mean a saving of Rs 1,000 crore (10% of 20 crore women beneficiaries given Rs 500 each).

Step 3: Unlocking unutilised funds: Rs 2,71,834 crore

There are many funds lying unutilised.

Unused Building and other Construction Workers Welfare (BoCW) Cess: On March 24, Labour and Employment Minister Santosh Gangwar issued an advisory to all states to transfer Rs 52,000 crore accumulated under the Building and Other Construction Workers' Welfare Cess Act of 1966 to construction workers. Official sources indicate that no progress has been made on this front so far due to administrative reasons.

Unclaimed PF: A sum of Rs 40,865 crore has been lying as unclaimed in Employees' Provident Fund (EPF) accounts since April 2017, according to a reply to the Rajya Sabha. With accumulated interest, this amount would have grown bigger now.

Unutilised CSF and GRE with RBI: On January 31, 2020, the RBI had a balance of Rs 1,28,098 crore in its Consolidated Sinking Fund (CSF) and Rs 7,346 crore in Guarantee Redemption Fund (GRE).

The state government maintains these funds with the RBI "as buffers for repayment of their liabilities" and they "can avail of Special Drawing Facility (SDF) from the Reserve Bank against the collateral of the funds in CSF and GRF" at 1 basic point below the repo rate.

Since these are state government funds, maintained for future exigencies, the entire amount can be made available to them in the current exigencies of COVID-19 and lockdown by making regulatory changes. This is what Bihar's Finance Minister Sushil Kumar Modi is hoping for, describing these funds as "lying unutilised".

That would mean unlocking Rs 1,35,444 crore.

World Bank emergency fund of $1 billion: In the meanwhile, the World Bank has granted $1 billion emergency fund to India for strengthening its infrastructure to contain COVID-19. This would mean availability of Rs 7,600 crore (at exchange rate of Rs 76).

Unutilised Mineral Development Fund: The Mineral Development Fund was set up in 2015 for the welfare of mining-affected communities. It has grown to Rs 35,925 crore.

Step 4: Assistance to self-employed, MSMEs and others

The above narration makes it clear that income support to the vulnerable segments would cost Rs 1.66 lakh crore: (a) cash support of Rs 6,000 to the bottom 40% of population or 104.7 million families (b) Rs 6,000 to 144.3 million landless and (c) Rs 16,570 crore of unemployment allowance to the MGNREGS job card holders.

Against this, pending dues, unlocking unutilised funds, PM CARES fund etc. would generate Rs 4.25 lakh crore: (i) Rs 69,006 crore of pending GST dues (ii) Rs 15,000 crore of health emergency fund (iii) Rs 68,487 crore of pending PM-KISAN payment (iv) Rs 1,000 crore of saving from misallocation of PMJDY (v) Rs 2,71,834 crore of unutilised funds

The rest of Rs 2.59 lakh crore can be used in the next step: assisting (i) underprivileged self-employed engaged in the informal economy (manufacturing and services) to restart their enterprises and (ii) MSMEs, hospitality, transport and other industries hit hard to open shops after the lockdown is lifted.

No comments:

Post a Comment