While India is firmly focused on AatmaNirbhar Bharat for a V-shaped recovery, its key fiscal numbers show the economy is slipping with falling capital expenditure, muted consumption and higher precautionary savings

Prasanna Mohanty | November 20, 2020 | Updated 12:08 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | November 20, 2020 | Updated 12:08 IST

India has been claiming a V-shaped recovery from the economic crisis by quoting high-frequency indicators that don't capture the informal sector constituting 45% of the GDP and without fully explaining what exactly such a recovery means.

Does it mean the economy will bounce back to the pre-pandemic level of growth?

If so, the latest fiscal numbers don't quite add up.

Before looking at these numbers, here is what the pre-pandemic growth level was.

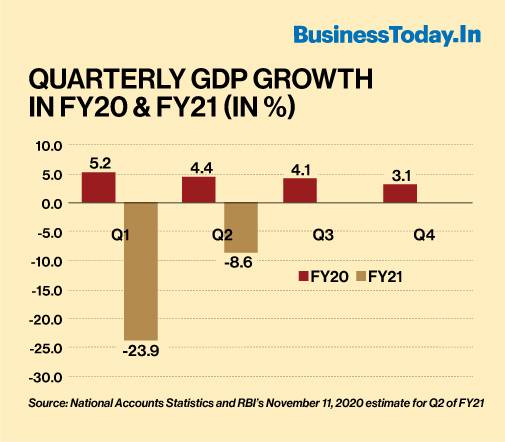

For the full fiscal of FY20 (lockdown began on March 25, a week before FY20 ended), the GDP grew at 4.2% - a sharp fall from 8.3% in FY17. The quarterly GDP growth numbers reflected a similar decline - from 5.2% in Q1 to 3.1% in Q4 of FY20.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 46: Who is designing India's growth path?

Post-lockdown, the first quarter (Q1) of FY21 saw the GDP nose-diving to minus 23.9% and the second quarter is likely to be minus 8.6%, according to the RBI's latest estimate although the official numbers would be declared later this month.

What do the latest fiscal numbers say about India regaining the FY20 growth level?

Here is a set of data on the central government's fiscal position in the first six months of FY21, released by the Controller General of Accounts (CGA).

What do FY21 fiscal numbers tell?

The CGA data shows the capital expenditure was much lower in July, August, and September 2020 (Q2) compared to the corresponding months of 2019. The gap reached Rs 21,701 crore by the end of September 2020 - a fall of 11.5%. Since capital expenditure drives growth, this would mean poor prospects for FY21 to match the FY20 growth level.

A similar trend is noticed in total expenditure, which slipped below the level of FY20 in August and September (two of three months of Q2) and the gap widened to Rs 9,209 crore (0.6%) by September 2020.

The fall in expenditure during the second quarter of FY21 is puzzling since unlocking began on June 1, a month before the second quarter started, and provided a better opportunity to raise it compared to the first quarter months.

Quite apparently, the central government prioritised containment of fiscal deficit over boosting growth.

It did achieve some success in September 2020 when the month-on-month fiscal deficit fell below that of 2019 - although the total fiscal deficit for the six-month period was higher by Rs 2.6 lakh crore.

India's fiscal conservatism, amply reflected in the liquidity heavy AatmaNirbhar Bharat packages, has attracted sharp criticism from several eminent economists because of demand recession that was noticed even in the pre-pandemic months.

Soon after the first quarter GDP number for FY21 was released (registering minus 23.9% growth), former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan wrote an article in September 2020 ("The Alarm in the GDP Numbers") likening the economy to a patient and said help (fiscal spending) was needed when the patient was still fighting the disease, else it might be too late and "self-defeating".

Last month, former Chief Economic Advisor (CEA) Arvind Subramanian wrote about India's fiscal conservatism warning it against "succumbing to intellectual mimicry of advanced countries on fiscal policy".

In an article co-authored with Shoumitro Chatterjee ("To embrace atmanirbharta is to choose to condemn Indian economy to mediocrity"), he argued: "India's interest rates are not at zero and are unlikely to be so because of persistent inflation. India's borrowing is still considered risky, reflected in ratings that are hovering perilously close to being classified as sub-par. The favourable interest rate-growth differential that supports expansionary policy in the advanced countries is absent in India. India may well have scope for expansionary fiscal policy in the short run but not as a medium run growth strategy."

Growth drivers muted

Why India's economy has tanked more than other major economies in its first quarter of FY21 is well known. As far back as May 1, 2019, the Monthly Economic Report of the finance ministry (for March 2019) had acknowledged the slowdown for the first time and said "the proximate factors" included "declining growth of private consumption, tepid increase in fixed investment, and muted exports".

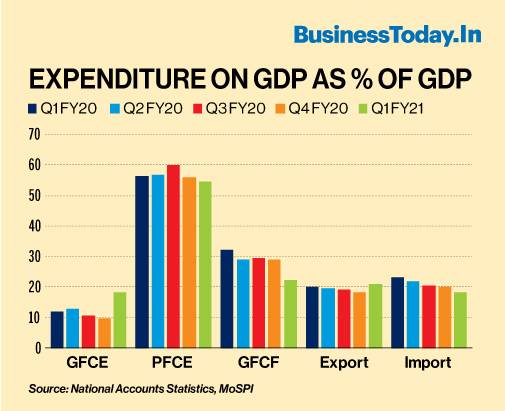

The following graph maps quarterly estimate of key growth drivers - government final consumption expenditure (GFCE), private final consumption expenditure (PFCE), gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), which includes both government and private investment, next export (export minus import) - from Q1 of FY20 to Q1 of FY21 to demonstrate how odds are stacked against high growth.

Except for government consumption (GFCE) and export other expenditures declined in Q1 of FY21.

The insistence on fiscal spending (government expenditure), as against fiscal conservatism, is because this can be mobilised quickly to deliver results in a shorter timespan while others need longer timeframes to get activated and deliver.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 43: States exhaust MGNREGS fund, leave Rs 1,386 crore in unpaid wages

The uptick in exports seen in the above graph is of little consequence since the net export remains negative for decades, reducing rather than adding to the GDP growth numbers.

The following graph from the RBI's November 2020 bulletin shows more recent trends. The bulletin points out that import has witnessed eight consecutive months of decline, which may have reduced the trade deficit but reflects lower domestic demand.

Households opting to save than consume

The bulletin carried more bad news.

It said the first quarter of FY21 saw a "significant increase" in household financial savings, indicating a pessimistic outlook on their future income.

It described this as "counter-seasonal", reflecting a reduction in discretionary spending and the associated "forced saving as well as a surge in precautionary saving".

It also pointed out that this trend was "consistent with" other available official statistics, like "decline in private final consumption expenditure" and "surplus position in the external current account".

Taken together, all these mean demand will remain sluggish, slowing down growth.

This is far from an ideal situation that would generate hope of a V-shaped recovery to match the FY20 numbers.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 42: How will changes to land laws in Jammu and Kashmir help, and whom?

Import substitution and walking out of RCEP

India's policy of import substitution embedded in the AatmaNirbhar Bharat Abhiyan and walking out on arguably the biggest trade deal, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), could prove counter-productive.

The RCEP involves 15 countries, including 10 ASEAN and two QUAD countries (Japan and Australia). Together, these countries account for 25% of global GDP, 30% of global trade, 26% FDI flow and 45% of global population. India walked out of it after nine years of negotiations.

External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar explained why: "In the name of openness, we have allowed subsidised products and unfair production advantages from abroad to prevail. And all the while, this was justified by the mantra of an open and globalised economy."

Here is a graph that shows how, indeed, trade has been unfair to India since 1971 - more so in recent.

Should India pull out of global trade and rely on AatmaNirbhar Bharat to deliver growth?

Even Arvind Panagaiya, one of the loudest cheerleaders of the government and first vice-chairman of Niti Aayog, disagreed. Subramanian and his co-author Shoumitro Chatterjee explained with facts and evidence why this was undesirable.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 41: India's growing poverty and hunger nobody talks about

In an article of October 2020 ("India's export opportunities could be significant even in a post-COVID world") they pointed out: "India's GDP growth of over 6 per cent after 1991 was associated with real export growth of about 11 per cent. Pre-1991, a 3.5 per cent growth rate, was associated with export growth of about 4.5 per cent. There is no known model of domestic demand/consumption-led growth, anywhere or at any time, that has delivered quick, sustained, and high (say 6 plus) rates of economic growth for developing countries."

They argued against import barriers saying: "First, foreign demand will always be bigger than domestic demand for any country. Second, there is also a fundamental asymmetry: If domestic producers are competitive internationally, they will be competitive domestically and domestic consumers and firms will also benefit. The reverse is not true: Being competitive only domestically is no guarantee of efficiency and low cost."

Sure, global trade has been unfair to many.

Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz and many other economists have exposed it, pointing out how global trade has caused widespread discontent not only in emerging and developing countries but also among millions of people in advanced countries (the US and Europe) due to multiple design flaws. These flaws helped developed countries more than developing ones and benefitted corporations at the cost of workers. They have sought to rewrite the rules but never suggested abandoning global trade or shutting one out.

There is another very significant reason why India can't afford to erect import barriers.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 40: Why Punjab farmers burn stubble?

Import is a significant driver of India's exports

Economists and trade experts are familiar with the phrase "import intensity of exports", which signifies the extent of imported inputs embodied in the goods being exported. In simpler words, it talks about import content in exported goods.

Delhi-based think tank Institute for Studies in Industrial Development (ISID) published a study in February 2020 titled "Import Intensity of India's Manufactured Export: An Industry Level Analysis", shedding light on it.

It said liberalisation of trade, post-1991 had led to rising imports, especially of raw materials and intermediate goods, which "contributed to the growing exports of India".

As for "import intensity" it found that for the "whole economy" it registered a dramatic rise from 10.5% in FY94 to 12.6% in FY99, 15.9% in FY04 and 32.5% in FY14 - presented in the following graph.

Clearly, the manufacturing sector benefitted the most. The import intensity for it grew from 29% in FY08 to 51% in FY14 (in a span of eight years). When different manufacturing segments were analysed, the study found petroleum products had 91.4% of import intensity in FY14.

The bottom line is that import restrictions will deliver a body blow to India's exports and jeopardise its future growth prospects.

Reviving inward-looking and failed experiments of pre-1991 era will only end up promoting inefficient and inferior local products and drag down growth to what economists call "Hindu" rate of growth. (For more read "Rebooting Economy 45: What is AatmaNirbhar Bharat and where will it take India? ")

Is India ready for the "Hindu" rate of growth?

No comments:

Post a Comment