Rebooting Economy 34: Temporary jobs hurt both workers and economy

Part II of this two-part article looks at more data on the growth of temporary or informal workers in India and how it poses a serious threat not just to the wellbeing of millions of its workers but to the growth prospects of the economy in the long run

Prasanna Mohanty | October 7, 2020 | Updated 11:44 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | October 7, 2020 | Updated 11:44 IST

The central government's big push to replace permanent and secured jobs with casual and contract jobs (temporary or informal) needs to be viewed with concern because while it facilitates maximisation of private profit, it also harms the wellbeing of millions of workers and poses a serious threat to productivity, skilling, economic growth and prosperity of India in the long run.

First, the good news.

Formal employment is growing but not significantly

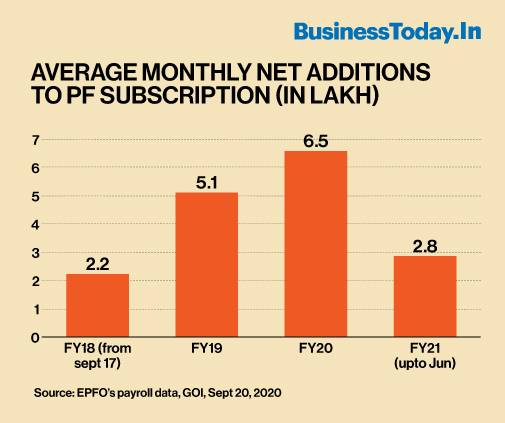

The Employees' Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) has been spreading cheers by reporting a rapid growth in PF subscriptions, an indication of formalisation of jobs and creation of new jobs in the economy.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 33: Where have the good old full-time decent jobs gone?

The net monthly additions to PF subscriptions since September 2018, when it began such reporting, have been worked out from its latest update released on September 20, 2020. The decline seen in FY21 is because of the lockdown propelled job losses.

A caveat, however, is in order.

Though Fixed Term Employment (FTE) was introduced in the Code on Social Security 2020 recently, the practice of short-term contract is an old one (two decades or more). Many such contracts do provide for PF subscriptions (not all) but only for the limited period of contract - up to a maximum of three years. It does not cover the entire working life of a worker (30 to 40 years or more).

There is no restriction on renewal of such a contract, but there is no legal provision to convert it into a permanent contract either. In practice, a short-fixed term contract is a permanently temporary job with no job guarantee even within the contract period. A contract worker can be fired at any time without fuss.

Further, the rise in PF subscriptions should be looked at from the perspective of the total workforce.

Prof. Ravi Srivastava of the Institute of Human Development (IHD) used the past four Periodic Labour Force Surveys' (PLFS) data and adjusted it with population projections for the respective years to work out how many workers in India are formal and how many are informal (in the entire economy) on the basis of written contracts. He treated those with written contracts as formal workers.

Here is what he found.

As the graph shows, workers with written contracts make up less than 8% of the total workforce. Those with any social security (one or more of PF, gratuity, healthcare, pension etc.) are just about 10% of the total workforce.

So, any addition to PF subscriptions is small when you look at the total workforce.

"Informal" workers in formal sectors have grown

Prof. Srivastava also mapped the share of informal workers in the formal sector, both in government and private, using the same PLFS data and using written contracts to determine formal workers. The findings are presented below.

As is clear, the share of informal workers has been growing in both formal government (public) sector and formal private sector. They have an overwhelming presence - 57% in public and 77% in private formal sectors in 2018-19.

The PLFS of 2018-19 saw a reversal in trend with a dip in the share of informal workers in formal private sector. This corroborates the rise in PF subscriptions.

Contract jobs hurt workers

For decades, India's "rigid" employment protection laws have been blamed for stunted growth of industries and employment in India. Popularised through the phrase "the missing middle", it is emphasised that India has a large number of tiny firms and a few very large ones but the middle-level ones are missing, depriving Indians from the benefits of industrialisation and job growth. Recent labour reforms are expected to clear the path.

While the labour law rigidity is not in dispute, the growth in contract jobs solely arising out of it is highly disputed and more often dismissed as insignificant. Academic studies show these rigidities "exist more on paper than in practice".

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 32: Wage code leaves millions of workers out in cold

A study on contract workers in manufacturing units, published in the journal Oxford Development Studies in June 2019, says, among other things: (i) "immediate cost advantages" tilt firms towards hiring contract labour and the labour law rigidity is "insignificant" in explaining the use of contract labour and (ii) there is no significant link between the proportion of unskilled workers and the probability of hiring contract labour (contract hiring is agnostic of skill levels in a firm).

It then goes on to add that "the effect of protective labour legislation on flexibility in the labour market (rigidity) is diminishing".

Another study of 2019 by the Delhi-based think tank ICRIER found the "rigidity" a mere excuse for something else.

It found: (i) contract work has grown in states which made their labour laws more flexible and "amenable to employers" (ii) contrary to expectations "it is the capital-intensive and not labour-intensive industries" which use contract workers more and (iii) "firms appear to be using contract workers to their strategic advantage against unionized directly hired workers to keep their bargaining power and wage demand in check".

The lead author of the study Prof. Radhicka Kapoor wrote elsewhere that it was no surprise that the real wages of directly hired workers has remained "almost stagnant over the last 15 years". Her study found the real wages of directly hired workers one-and-half times more than contract workers over the past decade.

Both studies point to lower labour costs and profit maximisation for hiring workers on contract.

There is more evidence of this.

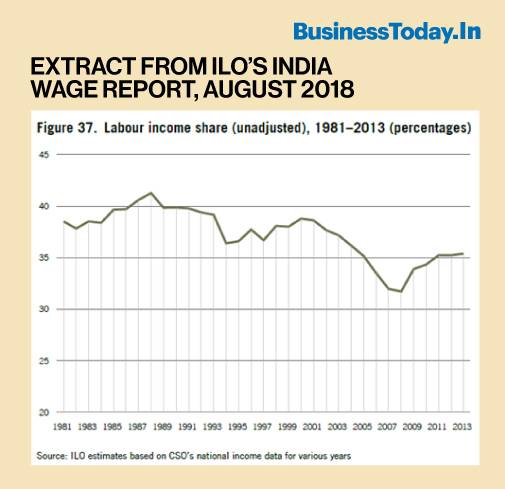

The ILO's 2018 India Wage Report says India experienced a decline in the share of labour income (wage) relative to labour productivity in the post-liberalised era. The average labour productivity increased more rapidly than real average wages - from 38.5% in 1981 to 35.4% in 2013.

This demonstrates that the gains in labour productivity went to employers.

The ILO report blamed "increasing flexibility in the labour market" for this decline in wage, adding: "Looking at the factors that affect wage share within an industry, it is argued that increasing flexibility in the labour market is the key factor contributing to this decline in wage share."

It pointed out that this flexibility has been achieved through "substitution of permanent employees with contract workers, increasing working hours, substitution of women for men as permanent workers, substitution of capital for labour, and substitution of technology for less skilled labour."

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 31: Will new labour codes protect more workers or less?

It warned that with the global rise in capital mobility and falling cost of capital, labour would be "further vulnerable and amenable to flexibility, control and discipline".

While limited in protecting workers' interest, India's new labour laws do not even provide for "equal pay for equal work" between temporary and permanent workers as mandated by the Supreme Court's 2016 judgement in the case of State of Punjab vs Jagjit Singh and others.

The Code on Social Security 2020 provides for equal pay between a Fixed Term Employee (FTE)-contract or temporary worker-and permanent employee of a firm, but not between FTEs themselves, who can be hired at different wages for the same or similar work. This is a normal practice in the private sector and depends on the bargaining power of individual workers.

There is no such protection for a vast majority of contract workers without a written contract. The PLFS of 2018-19 says 69.5% of regular wages/salaried in the non-farm sector have no written contract.

The Code on Wages 2019 removes pay discrimination between men and women but is silent on pay discrimination against ethnic minorities and lower castes. The ILO's 2018 India Wage Report found such pay discriminations (against women, ethnic minorities and lower caste groups) "a significant source of wage inequality" in India.

Contract jobs hurt economy too

Nobody argues that increase in contract jobs helps productivity or economic growth. It only helps private businesses cut labour costs, get away with little protection for workers and maximise profits.

The ILO's 2018 India Wage Report shows that temporary jobs bring low pay and wage inequalities and says these "remain aserious challengeto India'spath to achieving decent working conditions and inclusive growth".

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXX: Rural India in far deeper crisis than what govt data claims

The 2019 ICRIER study cited earlier studied labour productivity in organised manufacturing sector and found it was significantly higher for directly hired workers than those on contract, both in capital and labour intensive industries. Yet, it said, firms were hiring contract workers.

It also concluded that since contract workers can be easily shed and they work under "deplorable conditions" with little or no job security and fewer benefits in terms of health, safety, welfare and social security compared to directly hired workers, the "sustainability of employment growth driven by growth of contract workers is questionable".

Lower productivity would have long-term consequences for the economy. Besides, employers have no incentive to skill contract workers even if work is of "perennial" nature for which contract workers are banned under the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act of 1970 but permitted under the new labour codes, which also permit contract jobs even in "core activities" in certain circumstances. (For more read "Rebooting Economy 31: Will new labour codes protect more workers or less? ")

How do companies which require skilled labour to sustain high production and productivity levels manage to hire them on contract?

Here is an insight from the ILO 2016 report Labour Practices in India. It said: "For this purpose, most companies seem to have come toinformal agreements with contractors not to shift workers without their permission. In this manner the companies are able to secure the benefits of havinglow-wage but skilled workers."

Why India promotes temporary work even in government sector?

This is not difficult to explain.

Ever since India adopted the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act of 2003 to "ensure inter-generational equity in fiscal management and long-term macro-economic stability" fiscal austerity became the order of the day.

Also Read: Economy XXIX: Exposing farmers to unregulated market is more likely to harm them

This law limits India's fiscal deficit at 3% of the GDP and general government (Central plus state governments) debt at 60% of the GDP (for central government it is 40%). This is in keeping with the mandate of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which had bailed out India from its foreign exchange crisis, which led to the 1991 economic liberalisation.

These limits are, however, allowed to be relaxed in certain conditions, like the current crisis.

Since India's fiscal deficits have exceeded the limit for several years, the central government is severely constrained when it comes to fiscal spending, which is also reflected in its tight-fist when liberal spending is called for to kick-start the economy. In this endeavour, "revenue expenditure" (called "non-plan" expenditures until 2016 but this classification became irrelevant once the five-year plans and the Planning Commission were dismantled in August 2014) is the obvious target.

Few would argue against cutting down revenue expenditure, as against "capital expenditure" because the latter is considered a far more powerful driver of economic growth. Revenue expenditure mostly involves spending on wages/salaries, pensions etc. Hence, by keeping posts vacant and hiring workers on casual and contract basis helps.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVIII: Is India poised for agriculture-led economic turnaround?

Another development helped the central government in promoting contract workers in its domain.

In 2001, the Supreme Court "over-ruled" its earlier judgement of 1996 that had made it a statutory obligation for an employer to absorb a contractor worker where the contract system was abolished by the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970.

It said an employer can't be asked to absorb contract workers on a permanent basis, although it provided that they be considered first when an employer hires permanent employees and given preferential treatment.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVII: Fiscal mismanagement threatens India's economic recovery

With that protection gone, there is no compulsion for anyone to turn a contract into a permanent job.

The question, however, remains: Should the government jeopardise the wellbeing of its 400-500 million workforce, their families and ignore the long-term damage that contract work can inflict on the economic growth for short-term private gains?

Also Read:Rebooting Economy XXVIII: Is India poised for agriculture-led economic turnaround?

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVI: Derailment of economy is not 'Act of God', it is 'Art of Misdirection'

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXV: How a series of economic misadventures derailed India's growth story

No comments:

Post a Comment