Unprecedented demand for work under the rural job guarantee scheme sees 90 million individuals finding support and 19 million more waiting their turn, but if the fund crunch continues there may not be much to look forward to

Prasanna Mohanty | November 4, 2020 | Updated 12:28 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | November 4, 2020 | Updated 12:28 IST

While India battles a massive job loss scenario, the extent of which is not known because the central government has abdicated its responsibility to track it and take corrective measures, the state of the only effective job scheme that forms the lifeline for rural India, MGNREGS, has already lost steam.

This is bad news for rural India and the economy. It needs immediate attention as the country struggles to recover from the pandemic-induced crisis for a setback to the MGNREGS would adversely hit rural demand and delay the recovery.

It should not be forgotten that rural India contributes 46.9% to the GDP (national income) and 70.9% to the employment - as per the last such estimate carried out while rebasing of GDP to 2011-12. (For more read "Rebooting Economy XXX: Rural India in far deeper crisis than what govt data claims ")

A scrutiny of the MGNREGS database reveals many shocking details.

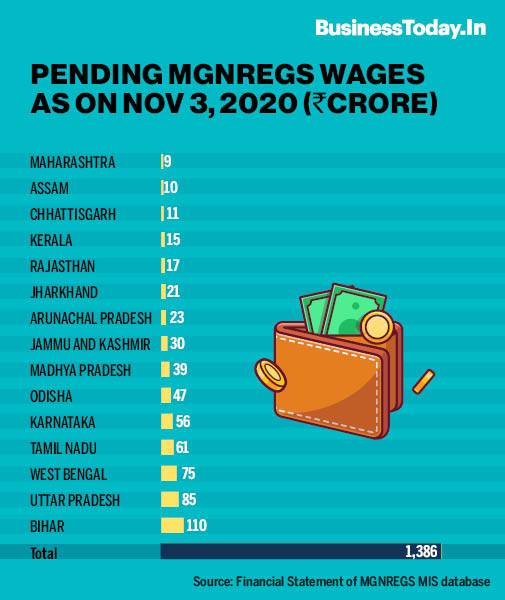

Many states exhaust funds; report Rs 2,000 crore shortfall, Rs 1,386 crore in unpaid wages

As on November 3, 2020, many big states have exhausted their MGNREGS funds and the gap between the total funds available and total expenditure on wages, materials and administration of the scheme has risen toRs 2,136 crore.

Four states, Telangana, Karnataka, Bihar and Andhra Pradesh, have recorded a gap of more than Rs 500 crore each.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 42: How will changes to land laws in Jammu and Kashmir help, and whom?

The following graph captures the financial status of some of the big states, based on the MGNREGS database.

While it is understandable that Kerala and Gujarat would have surplus funds at this time of the year because these are low-MGNREGS demand states, more so during the harvesting season, what should be worrying is the huge surplus with West Bengal, Jharkhand, Assam, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan - home to a large number of poor needing the MGNREGS lifeline.

The poor overall financial status also means that wages of millions who have already worked remain unpaid. The official data ("Financial Statement") shows, as on November 3, 2020, Rs 1,386 crore in wages remained unpaid.

This is 65% of the total shortfall in the MGNREGS fund with states.

The lack of funds is particularly distressing given that India is struggling to recover after a massive drop in the first quarter GDP growth (by minus 23.9%). India's growth prospect for the entire fiscal also remains grim (minus 10.3% and minus 9.5% as per the IMF and RBI estimates, respectively).

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 41: India's growing poverty and hunger nobody talks about

Given the fact that much of the economic crisis is on account of the untimely, unthinking and unplanned national lockdown (social and economic) announced on the night of March 24 with a four-hour notice, the central government owes it to the people and states to provide immediate support.

So far, the Centre has released Rs 70,997 crore (as on November 3, 2020), out of Rs 101,500 crore earmarked for FY21 (budget allocation of Rs 61,500 crore and additional relief of Rs 40,000 crore). Out of this, Rs 4,431 crore was meant for the pending dues of FY20.

Unless the central government releases the remaining Rs 26,072 crore (Rs 101,500 minus Rs 4,431 minus Rs 70,997 crore), a large number of states are unlikely to sanction new work or pay pending wages any time soon.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 40: Why Punjab farmers burn stubble?

9.5 million households, 19 million individuals waiting for work

That the demand for manual work under the scheme has skyrocketed is evident from the number of households and individuals demanding or getting work. Records show that in September-October 2020 the demand for work went up to 48.7 million, from 27.2 million in the corresponding months of FY20, for households and to 55.2 million from 33.7 million for individuals.

The work given under the scheme has also seen a corresponding increase. The months of September-October 2020 saw the number of households getting work go up to 36.3 million from 23 million in the corresponding period of FY20 for households and to 447.4 million from 285 million for individuals.

Simultaneously, the unmet demand has shot up too.

As on November 3, 2020, a total of 9.5 million households and 19 million individuals were waiting for work. In percentage terms, these numbers work out to be 13% for households and 17% for individuals seeking work.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 39: Why nobody questions industries polluting Delhi air the most?

The following graph maps the worst performing states where the unmet demand has gone up very high. The cases of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Odisha are particularly worrying given that these backward states have a large number of poor.

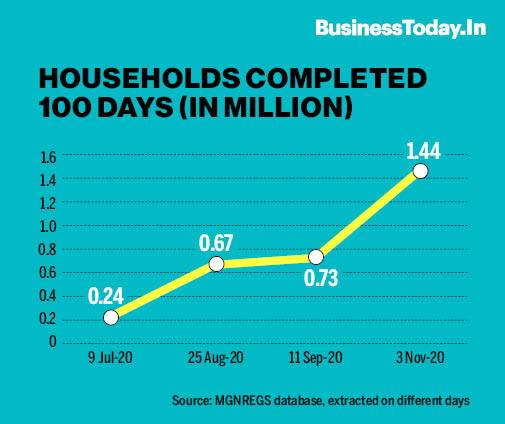

Analysis of the official data extracted at different points of time during the pandemic shows that after an initial high the unmet demand went down in August and September but has risen sharply in November.

The MGNREGS is a demand-driven programme under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act of 2005, which gives a statutory guarantee to provide work on demand. If no work is given for 15 days, all those demanding work are entitled to unemployment allowance. This provision remains on paper, unenforced even during the current crisis.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 38: What makes stock markets and billionaires immune to coronavirus pandemic?

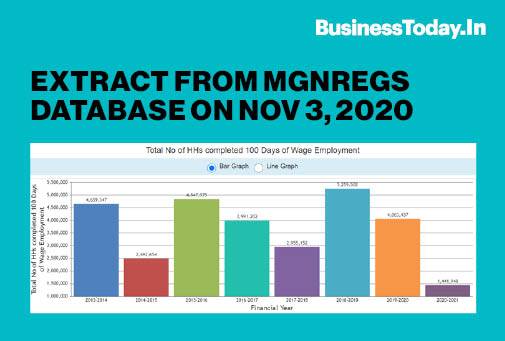

Days of work provided are far lower than at any time in the past

It is also shocking to note that despite the current crisis and high demand for work, the average number of days of work given under the scheme is nowhere close to earlier years.

In fact, at 38.81 days, the average days of work per household in FY21 are at the lowest since 2014.

So is the case with households completing 100 days of work.

The good news, however, is that during the pandemic, the number of those completing 100 days of work is going up.

63 million households, 90 million individuals found work under MGNREGS

The significance of the scheme, which provides manual work, would be clear from the number of beneficiaries.

The official data shows, as on November 3, 2020, 63 million households and 90 million individuals have worked under the scheme during the current fiscal year.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 37: Do high-frequency data suggest V-shaped recovery?

The numbers for earlier years are no less gigantic. In the past few years, households benefiting from it have ranged 51.2-54.8 million and individuals ranged 76.7-78.9 million.

As the above graph shows, the numbers are steadily rising, indicating lack of better paying jobs.

The MGNREGS is a very low-paying work, less than even the minimum wages of states. The central government's rate, after a raise of Rs 20 announced in April 2020 as economic relief for massive job losses, went up from a mere Rs 182 to Rs 202.

Need to raise MGNREGS allocation several times higher

That the allocations for the scheme need to go up substantially to the current level is not in doubt. It remains a mystery why this did not happen in the past.

Right from the beginning of it in 2005, economists and experts argued for far greater allocation given the rural distress and wide-spread poverty. Rinku Murgai of the World Bank and Martin Ravallion of the Georgetown University had argued then that it should be around 1.7% of the GDP.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 36: Job creation is nobody's business in India

In their January 2005 paper "Employment Guarantee in Rural India: What Would It Cost and How Much Would It Reduce Poverty?" they reasoned: "At the current statutory wage rate, the scheme may helpreduce rural poverty to 23 per cent(30 per cent year-round), at a cost of1.7 per cent of GDP."

The highest ever fund of Rs 101,500 crore earmarked for FY21 is just 0.7% of the GDP of FY20 (first revised estimate of Rs 145.66 lakh crore at constant price).

The current economic crisis and lack of proper policy or strategy on employment generation make it even more important that the MGNREGS gets the maximum fiscal support from the central government.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 35: Is fixed term employment a boon or bane for India's workforce?

No comments:

Post a Comment