The private corporate sector simply does not need to invest more because lack of demand has forced it to cut production and capacity utilisation for several years now. Besides, growth in employment is happening elsewhere (not in manufacturing) where the relation between investment and employment growth is tenuous.

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: October 1, 2019 | 18:10 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: October 1, 2019 | 18:10 IST

It is time to get more realistic about the structural changes taking place in the Indian economy through more studies and more reliable data and moderate expectations.

On September 20, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a corporate tax cut for domestic firms and new domestic manufacturing companies - from 30% to 22% for the former and from 25% to 15% for the latter. "Tax concessions will bring investments in Make in India (manufacturing), boost employment and economic activity, leading to more revenue" she declared.

But will it? Here is a reality check.

Investment boost: A myth

Analysing saving and investment patterns in the economy, the RBI in its report of March 31, 2019, said that private corporate sector's savings have consistently been going up for many years - from 9.5% of the GDP in FY12 to 11.6% in FY18 - while its investments (Gross Capital Formation) have been falling - from 13.3% to 12.1% - during the same period.

It concludes: "In recent years, the private corporate sector's saving-investment gap has almost closed and most of its investment is financed through its own saving, indicating a falling appetite for fresh investment.

Also Read: Decoding Slowdown: Dip in household savings, investment an indicator of structural economic slowdown

The RBI does not explain why the private corporate sector has lost its appetite for fresh investment but its own database does.

The database shows there is no incentive or demand for investment because the consumption demand is on a prolonged decline, which gets reflected in poor capacity utilisation (CU) and production of manufacturing goods and services.

Capacity utilisation (CU) measures the extent of utilisation of existing capacity. The data shows this has fallen and is largely confined to a lower band of 70-75% since FY13. The last time it touched the 80% mark was way back in FY10 and FY11.

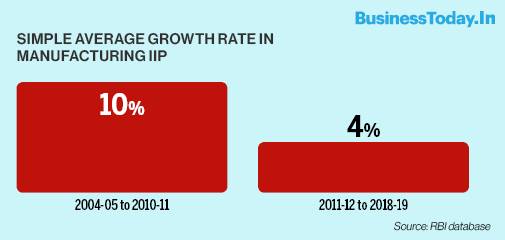

Index of Industrial Production (IIP) measures production in the areas of mining and quarrying, manufacturing and electricity. Growth in the manufacturing IIP (which has 77.63% weightage in the 2011-12 series) has also slowed down to about 4%, on an average, between FY12 and FY19.

This rate is not well below the GDP growth rate for all these years but also well below that of its own growth during the previous six years of FY05-FY11 (2004-05 base) - when it averaged 10%.

Why would anyone invest in manufacturing then?

The surplus money (from corporate tax cut) is more likely to be spent elsewhere - conspicuous consumption, speculation or something else.

The US experience shows how.

Also Read:Decoding Slowdown: Govt apathy and low investment continue to plague the agriculture sector

US experience of corporate tax cuts: Impact on investment uncertain

The US had cut corporate tax in 2017 (from 35% to 21%) on similar arguments, but unlike India, it had also cut payroll and individual income taxes as well.

On May 22, 2019, the US Congress released a study on its impact and concluded, among other things, by saying, "Although investment grew significantly, the growth patterns for different types of assets do not appear to be consistent with the direction and size of the supply-side incentive effects one would expect from the tax changes."

Labour economist Prof KR Shyam Sundar of the XLRI, Jamshedpur, explains what this means, "This simply means that the impact of corporate tax cut on investment is not certain and even if it has a positive effect on investment, the magnitude of that effect would depend on several other macroeconomic variables."

Interestingly, the cut in corporate and payroll taxes led to a loss of revenue by $40 billion and $7 billion, respectively, while that in individual income tax improved revenue collection by $45 billion. Not just that, the exercise led to an increase in consumption by 0.4% in the GDP "due to private consumption".

There was "no indication of a surge in wages", as was promised. The gain, instead, went into "record-breaking amount of stock buybacks, with $1 trillion announced by the end of 2018".

Nobel laureate Paul Krugman had earlier commented that "the tax cut seems to have produced some biggish financial activity on the part of corporations, but it's all basically accounting manoeuvres signifying nothing". He had also said that the corporate tax cut "had few real consequences for the economy".

Impact on job creation: Little or uncertain

No fresh investment would mean no employment either. But there is another aspect to investment and employment which has attracted little attention.

Prof Satyaki Roy of the Institute for Studies in Industrial Development (ISID) studied co-relation between the two for sectors which witnessed relatively higher employment growth between 1980 and 2004 (Structural Change in Employment in India since 1980s: How Lewisian Is It?). He found "no causality".

His study found that relatively higher growth in employment had happened in sectors other than manufacturing - construction; trade, hotels and restaurants; transport, storage and communication and financial services - and this growth had not happened due to higher investment. On the contrary, the share in investment (GFCF) with respect to employment for these sectors had sharply declined.

He offers three insights to explain something that goes against the conventional economic wisdom: (a) growth in employment in these sectors was because a large number of people were pushed out of agriculture because of declining income (b) this led to dramatic rise in unorganised workers in those sectors (more than doubled) and that (c) manufacturing and services sector like financial services had become more capital intensive and higher investment in these sectors would not raise employment proportionately.

A similar exercise carried out for the period between 2000 and 2018, using the ILO data for employment - which is used by the RBI (Report of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit, Sept 2019) as well as the Economic Survey- and the National Accounts Statistics for investment (GFCF). The finding is starkly similar.

But before that, here is what the ILO data on employment reveals: just like Prof Roy's study, growth in employment has happened less in manufacturing and more in other sectors - construction, financial services, transport and real estate.

As for the correlation between investment (GFCF) and employment in these high employment growth sectors, the following four graphs would make it clear that establishing a causality, even if one were to take the time lag factor (investment takes time to show up in higher employment), is tenuous.

While this phenomenon calls for further study to know what exactly is happening, Prof Roy says the implications are clear though: The surplus generated by the corporate tax cut is unlikely to be invested in manufacturing because of poor consumption demand in the economy and less than enthusiastic outlook for consumption expenditure that the RBI consumer confidence surveys show.

It is time to get more realistic about the structural changes taking place in the Indian economy through more studies and more reliable data and moderate expectations.

No comments:

Post a Comment