Decoding Slowdown: Studies show that Indian farmers have been short-changed by Rs 45 lakh crore of income during 2000-2016 due to complex market regulations and restrictive trade policies and that credit flows to agriculture is being used for non-agricultural purposes.

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: September 27, 2019 | 22:14 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: September 27, 2019 | 22:14 IST

Decoding Slowdown: This is ironic since agriculture remains the biggest source of livelihood in India and it is the slump in consumer demand, particularly in rural areas dependent largely on agriculture, which is the latest drag on India's growth story.

When it comes to reviving economic growth, agriculture is often ignored. A good example is the flurry of recent policy announcements - cut in corporate tax, bank mergers, recapitalisation of banks, cut in the GST, higher depreciation on vehicles etc. There is very little for agriculture, at least directly, in these announcements.

This is ironic since agriculture remains the biggest source of livelihood in India and it is the slump in consumer demand, particularly in rural areas dependent largely on agriculture, which is the latest drag on India's growth story.

Also Read: Decoding Slowdown: Dip in household savings, investment an indicator of structural economic slowdown

High dependence, low income

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the UN says that about 70% of India's rural households "still depend primarily on the agriculture sector for their livelihood." According to the Economic Survey of 2017-18, this sector accounted for 49% of India's total workforce but earned just 16% (or less than 1/6th) of the total income (GDP).

More recently, an RBI report quoted the International Labour Organisation (ILO) to say that the agriculture's share in total employment came down to 44% in 2018 (financial year), while its own estimates pointed out a 14.4% share in the national income for FY19.

What all these mean is that while agriculture continues to provide the maximum livelihood, its share in the national income continues to fall - from 22.6% in FY05 to 14.4% in FY19.

Source: RBI database (Components of Gross Value Added at Basic Price)

It is in this context that a low growth rate in agriculture is a cause of serious concern.

A comparative analysis shows the simple average growth rate of the agriculture GVA has been exactly half that of the overall GVA (of the economy) during FY06 and FY19.

Source: RBI database: Sectoral Growth of GVA at 2011-12 Prices

Denying farmers their income

Why does agriculture remain a low-income activity?

A 2018 OECD-ICRIER study, Review of Agricultural Policies in India provides a good answer: denial of income to farmers.

It says India's complex market regulations and restrictive trade policies combine to reduce gross farm revenues, in spite of a host of subsidies (fertilizers, power, irrigation etc.).

It measured this by using the producer support estimate (PSE) - an indicator of the annual monetary value of gross transfers from consumers and taxpayers to agricultural producers, measured at the farm gate level, arising from policy measures that support agriculture.

It found the PSE for India to be minus (-) 14% of gross farm receipts, on an average, for the study period - 2000 to 2016.

Prof Ashok Gulati of the ICRIER who co-led the study translated this to loss of income for the Indian farmers - Rs 2.65 lakh crore per annum, at 2017-18 prices or Rs 45 lakh crore, at 2017-18 prices, cumulatively for 17 years. He describes this as "nothing short of plundering of farmers' income".

The implications are very clear, the restrictive mechanisms need to go.

While the study offers a host of suggestions, Prof Gulati emphasises on two: (a) dismantling of institutional structures like the Essential Commodities Act and Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs), both of which are restrictive and deny better price realisation and (b) switching from price policy approach (such as input subsidies, interest subventions etc. including crop insurances) to direct income support for farmers by transferring the entire cost of it.

Falling private investment

One of the reasons for low growth is low investment. Starting with the National Agriculture Policy of 2000, efforts have been made to improve investment, particularly private investment.

But the official data shows that between FY12 and FY17 - the period for which comparative data are available - public investment remained more or less static at 0.3-0.4% of the GDP ( 2011-12 base, market price) while private investment fell from 2.7% to 1.8% - dragging the overall investment from 3.1% of the GDP to 2.2%.

Source: Agriculture Statistics 2017 (2011-12 Base, Market Price)

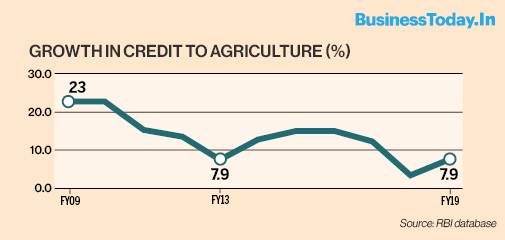

This is evident in the fall of growth in credit outflow since FY09.

Source: RBI database

Falling long term credits

The fall in overall credit is marked by lower credits outflows for investment.

The RBI's Report of 'Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit', released in September 2019, shows that the share of short term loans is soaring because of the interest subvention scheme started in FY07.

Source: RBI's Report of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit, Sept 2019

The interest subvention was meant to boost short term crop loans (production credit) but it has led to the fall in long term loans (investment credit).

There is more to it.

Diversion of credit for non-agricultural use

The RBI's internal working group report also found that some states are getting agri-credit far higher than their entire agri-GDP, indicating diversion of credit for non-agricultural use.

These are: Kerala (over 180% of agri-GDP), Tamil Nadu (170-180%), Telangana and Punjab (over 100%).

Then, some states are also getting significantly higher credit than their input costs - Andhra Pradesh (7.5 times), Kerala (6 times), Goa (5 times), Telangana, Tamil Nadu and Uttarkhand (4 times) - raising questions about its use.

Prof Gulati explains that this is because of high arbitrage (gap) in the interest rates for agriculture and other sectors. Farmers get a concessional interest rate of 7% for short term crop loans, 2% interest subvention and 3% prompt repayment incentive making the effective rate of interest to be 4% - while that for other sectors is 10% or more.

So as long as this gap remains, diversion of agri-credit would continue, he warns.

Policy response: Piecemeal and half-hearted

In recent years, the main thrusts of responding to agrarian distress have been a higher minimum support price (MSP), higher allocation for the rural employment scheme (MGNREGS) and an annual income transfer of Rs 6,000 to farmers (PM-Kisan scheme).

A higher MSP had led to a crash in prices in agricultural markets across the country in 2018, defeating the very purpose. The MGNREGS continues to suffer from two major problems: (a) wage rates are below the minimum wages of corresponding states and (b) the central budgetary allocations are lower than the actual expenditure for the past few years.

The low wage is a concern because it constitutes a major proportion of income for nearly half of rural households - 34% of agricultural households and 54% of non-agricultural households - as per the NABARD's All India Rural Financial Inclusion Survey of 2016-17.

As for the PM-Kisan scheme, it leaves out the poorest of the poor in rural India - agricultural labourers - which constitute 55% of the total agricultural workforce, as against 45% of farmers (cultivators).

No comments:

Post a Comment