Landless, marginal, and small farmers together constitute 93.7% of the total agricultural workforce in India. Can sustainable agricultural growth and farmers' well-being be achieved without land reforms?

Prasanna Mohanty | December 14, 2020 | Updated 14:02 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | December 14, 2020 | Updated 14:02 IST

While farmers' protest has occupied the political centre stage, India has forgotten the other part of the agricultural workforce: landless agriculture workers who also double-up as tenant farmers and sharecroppers and are officially recognised as "poorest of the poor".

Their contribution to agricultural output is immense given the widespread absentee (farm) landlordism. One estimate suggests that they contribute up to 40% of the total output. No government policy, least of all the three new farm laws and the PM-Kisan, counts them or provides any assistance.

They are the invisible farmers of India.

Invisible farmers: 55% total agricultural workforce is landless

The number of landless farmers in India has grown steadily since the 1951 Census to overtake that of farmers (cultivators) by 2011, accounting for 55% of the total agriculture workforce. Their number stood at 144.3 million, as against 118.8 million farmers (cultivators) in 2011 - growing 5.3 times since 1951.

Is this a sign of India's economic growth?

They are also not part of the government's flagship "doubling farmers' income" mission.

In fact, the Ashok Dalwai Committee (volume XIII), set up in 2017 to suggest measures for doubling farmers' income, went out of its way (not its mandate, it said) to flag this point, stating how the National Commission on Farmers (NCF) of 2007 had "considered both landowning and landless agriculture workers as farmers" and pleaded that this should be accepted and they be given all benefits meant for farmers. It listed these benefits as seed kits, fertilisers, pesticides, farm machinery, micro-irrigation, land development assistance etc. which are denied to them (given only to those who can prove land ownership).

The committee also highlighted the old laws, policies, and practices which it said had "driven positive change" but are now considered an "impediment".

The committee referred to the old Land Revenue Acts of state governments, which it said had helped the landless, as well as tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and lessees, to "gain ownership and unhindered access to land, thereby incentivising them to invest in agriculture, adopt new technologies and farm management practices and produce more".

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 50: Economic reforms for whom and for what?

It counted "pro-people land reforms", adoptions of high-yield varieties, procurement of farm produce at MSP, and others that "constituted a positive policy framework" that ushered in the Green Revolution in the country and lamented that "the very laws that had earlier driven a positive change... are in some ways now seen to be becoming an impediment to sustaining the pace of that progress".

The committee's suggestions were ignored and landless farmers don't find a place in the three new farm laws.

Most state governments also ignored landless farmers.

The only radical new approach to agriculture in recent years is the income support scheme, first started with Telangana's Rythu Bandu scheme in which farmers get Rs 10,000 per acre per year, but landless or tenant farmers get nothing. Several other states followed this model, like West Bengal and Jharkhand; Odisha alone made a departure by providing Rs12,500 to landless families, while giving a lower amount, Rs 10,000, to small and marginal farmers.

The central government borrowed this idea by launching the PM-Kisan scheme just ahead of the 2019 general elections. Under this scheme, all farmers, small, marginal, and big, get Rs 6,000 a year, but not landless farmers or tenants and sharecroppers.

86% of all farmers are small and marginal

The Dalwai Committee also recommended that small and marginal farmers, constituting 86% of all farmers, be given special treatment because their financial constraints and other issues (low literacy/ skilling, etc.) made it tough for them to adapt to the climatic change-related challenges.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 49: Who needs corporates to run banks and how will it help Indian economy?

Talking about contract farming, it said small and marginal farmers should be allowed to participate "while protecting their interests, including land rights in particular", although it pointed out that the global experience showed contract farming "has not been able to easily attract small and marginal farmers".

Though small (less than 2 hectares) and marginal (less than 1 hectare) farmers constitute 86% of all farmers at the national level, in several states, they are more than 90% - as would be clear from the following graph.

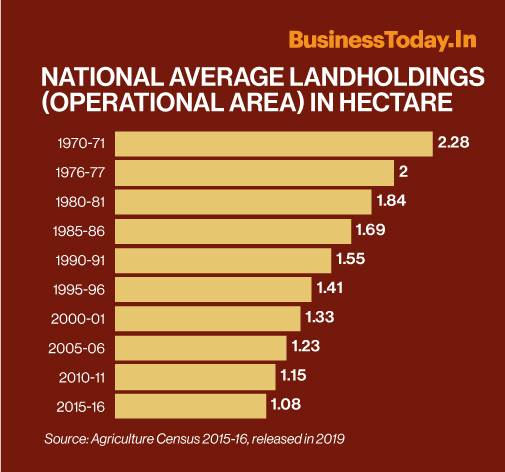

The average landholdings (operational) are also small.

At the national level, farm holdings have gone down drastically - as the following graph from the last Agriculture Census of 2015-16 shows.

Taken together, landless farmers (55% of the total agriculture workforce of 263.1 million), small and marginal farmers (86% of all farmers) constitute 93.7% of India's total agriculture workforce.

They can be ignored at a very high cost to India's economy.

Why and how agricultural landholdings were lost?

It took years for Indian policymakers to realise that agricultural landholdings were slipping badly.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 48: Do tax numbers show a healthier economy?

Faced with a tough battle against the Maoists in the tribal belt of central India, the rural development ministry sat up and produced a report, "State Agrarian Relations and Unfinished Task of Land Reforms", in 2009.

The report said not all blame could be placed on the 1991 liberalisation. Other factors contributed too: "...non-agricultural demands placed on land on account of industrialisation, infrastructural development, urbanisation and migration of the urban rich in the rural areas have certainly contributed to the process".

How much land was lost thus?

The report quoted eminent sociologist Walter Fernandes' old estimate that 60 million people had been dispossessed of their land during 1947-2004, involving 25 million hectares (about 40% of them were tribals). As for land loss by tribals, it said this was "the biggest grab of tribal lands after Columbus" in which the state was complicit (forcible land acquisition under the colonial law, Land Acquisition Act of 1894).

How many of those who lost their land resettled?

There is no estimate, but it is generally agreed that very few. This is what the 2013 land law wanted to rectify after a Parliamentary Standing Committee report of 2012, headed by BJP leader Sumitra Mahajan, told the Manmohan Singh government, "Since there is no question of the State acquisition of labour or capital, even at the margin, why should the State at all be involved in acquiring land, which is the most precious and scarce of the three factors for production, for private enterprises, PPP enterprises, or even public enterprises? When in developed countries like USA, Japan, Canada, etc. land is purchased by such enterprises rather than acquired by the State, why should India in the 21st Century persist with this anomalous practice?"

Why land matters to farmers needs no explanation.

Yet here is what the 2013 draft National Land Reform Policy (never debated or officially adopted) said: "Landlessness is a strong indicator of rural poverty in the country. Land is the most valuable, imperishable possession from which people derive their economic independence, social status, and a modest and permanent means of livelihood. But in addition to that, land also assures them of identity and dignity and creates conditions and opportunities for realising social equality. Assured possession and equitable distribution of land is a lasting source for peace and prosperity and will pave way for economic and social justice in India."

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 47: Do India's fiscal numbers suggest a quick turn-around?

These facts are acknowledged, but all official committees since then have skirted around it.

Niti Aayog produced a report to promote land leasing to overcome this issue in 2016 ("Report of the Expert Committee on Land Leasing" led by T Haque). The same year a model leasing law was circulated to states. The Dalwai Committee report endorsed it and talked about contract farming, farmer producer organisations (FPOs), land leasing, etc. to address landlessness.

Growing gap in rural-urban income

That India needs to go beyond just contract farming and private trading is obvious.

The following graph is from the Niti Aayog's 2017 report "Doubling Farmers' Income" which shows 22.5% of farm households live below the official poverty line at the national level but go as high as 45.3% in Jharkhand and 32% in Odisha.

Here is another indicator.

The gap in income between rural and urban population is growing over the decades.

The following graph is based on the official statement issued in 2018, giving estimates of per capita rural and urban income, which are estimated only at the time of GDP base-year revision.

The following graph presents per capita Net Domestic Product (NDP) for 1999-2000 and 2004-05 and Net Value Added (NVA) for 2011-12 for urban and rural areas.

Here is a global perspective on Indian agriculture.

This table is taken from a study, "Revisiting Domestic Support to Agriculture at the WTO: Ensuring a Level Playing Field", by the Indian Institute of Foreign Trade (IIFT), published in June 2020.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 46: Who is designing India's growth path?

It shows how India's agriculture not only sustains a very large population, but it also provides the maximum employment (more than 41%), and yet it is also a very low-income activity (14% of the GDP) - unlike anywhere else in the world.

For the record, except for West Bengal, Kerala, and Jammu & Kashmir, states "did not implement in the true spirit" the land reform measures of 1950s and 1960s, says the 2013 draft National Land Reforms Policy.

At a time when land reform is a "no-go" area, landless, small, and marginal farmers have an option: switch to non-farm sectors. But that has also turned out to be a "no-go".

The new growth paradigm (capital and technology-driven that creates fewer jobs), prolonged economic slowdown, and the lockdown-induced economic crisis have drastically reduced the scope.

India first witnessed job-less growth and then job-loss growth.

Two studies by the Azim Premji University (both analysing official data) - "The State of Working India, 2018", "India's Employment Crisis: Rising Education Levels and Falling Non-agricultural Job Growth, 2019" - amply demonstrated that.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 45: What is AatmaNirbhar Bharat and where will it take India?

Its 2018 study said: "In the 1970s and 1980s, when GDP growth was around 3-4 per cent, employment growth was around 2 per cent per annum. Since the 1990s, and particularly in the 2000s, GDP growth has accelerated to 7 per cent but employment growth has slowed to 1 per cent or even less."

The 2019 study said 9 million jobs were lost between 2011-12 and 2017-18.

Agricultural workers did move to non-agriculture sectors in large numbers in the past and found work in low-skilled industry, services, and construction sectors. But these sectors have received severe setbacks due to a prolonged economic slowdown that started well before the pandemic hit.

The last resort for landless, small, and marginal farmers could be to dig up ponds and lay mud-tracks, etc. that the low-paying (menial work), rural job guarantee scheme, MGNREGS, offers.

That too is not in good shape.

Here are three indicators of MGNREGS's functioning, as it stood in official records as of December 11, 2020.

- High unmet demand: 9.9 million for households and 20 million for individuals (13% and 17% of the demand, respectively).

- Below par days of work (average) provided:41.7 days in FY21(as on December 11, 2020) as against 48.4 days in FY20, 50.9 days in FY19, 45.7 days in FY18, and 46 days in FY17.

- High unpaid wages: Rs 1,510 crore.

It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that India needs land reform urgently to ensure people's well-being and sustainable economic growth.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 43: States exhaust MGNREGS fund, leave Rs 1,386 crore in unpaid wages

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 42: How will changes to land laws in Jammu and Kashmir help, and whom?

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 41: India's growing poverty and hunger nobody talks about

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 40: Why Punjab farmers burn stubble?

No comments:

Post a Comment