RBI panel's proposal to allow big corporates/industrial houses to own and run banks and NBFCs is contrary to RBI's own earlier stand, economic logic and historical evidence of multiple economic crises caused by reckless private financial sector players

Prasanna Mohanty | February 10, 2021 | Updated 19:44 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | February 10, 2021 | Updated 19:44 IST

A series of economic "reforms" have been unleashed since 2016 that defy economic logic - from the demonetisation of 2016 to the AatmaNirbhar Bharat of 2020. The latest one on the block is to let big corporate/industrial houses run banks. Interestingly, this is the only "reform" which hasn't dropped out of the blue at nightly live-telecasts; it is a mere proposal at present, but with far reaching consequences if pursued.

This proposal comes from the RBI's internal working group (IWG) report released on November 20, 2020 stating: "large corporate/industrial houses may be allowed as promoters of banks" and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs or shadow banks) owned by corporate houses "may be considered for conversion into banks".

It does not explain why it desires so, except making a general case for improving credit flows to make India a $5 trillion economy but without considering why India and developed economies like the US have studiously avoided such a course for decades.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 48: Do tax numbers show a healthier economy?

Why economists opposing big industries running banks?

All of India's top economists with wide national and international exposures strongly oppose this reform proposal.

Former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan and former Deputy Governor Viral Acharya, who should know better about banking, wrote an article "Do we really need Indian corporations in banking?" describing it as a "bombshell" and "best left on the shelf".

They offered two arguments against it: (i) industrial houses will get finances from banks they run with no questions asked (even though not their own money but public deposits), that the history of such banks (connected or related-party lending) "is invariably disastrous" and (ii) it will "exacerbate" concentration of economic and political power, making India susceptible to "authoritarian cronyism".

They flagged a third point though didn't list it: (iii) banks are rarely allowed to fail in India, as in the recent cases of Yes Bank and Lakshmi Vilas Bank, in which case public depositors and taxpayers will bear the burden of bailouts, NPA write-offs and remonetisation as and when these banks fail.

Seen from this perspective, the IWG's proposal is a win-win-win proposition for big businesses but lose-lose-lose for public depositors and taxpayers (loss of deposits, opportunity cost of not investing in better projects and cost of bail-out/remonetisation).

Two former chief economic advisers of India (CEAs) and a former finance secretary of India, Arvind Subramanian, Shankar Acharya and Vijay Kelkar, also opposed it.

They wrote ("A capital mistake") with a dire warning: "The conclusion is clear. Mixing industry and finance will set us on a road full of dangers - for growth, public finances and the future of the country itself. We sincerely urge policymakers not to take this path."

They listed three reasons: (a) over-finance of risky activities (due to connected-lending or related- party transactions banned by multiple Indian laws) (b) encourage inefficiency by delaying exit and (c) entrench their dominance.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 47: Do India's fiscal numbers suggest a quick turn-around?

Another former CEA and former World Bank chief economist Kaushik Basu warned that it is "almost invariably a step towards crony capitalism, where a few big corporations capture the business space in the country, slowly edging out the smaller players".

He pointed out: "There is a lot of evidence that connected lending was the biggest cause of the build-up of bad loans in 1997 in Asia, which resulted in the East Asian Crisis that began in Thailand and turned out to be one of the biggest financial crashes in the world."

Why now when banking system is in deep crisis?

Rajan and Acharya raised this question and offered two reasons.

Firstly, they wrote, "the government wants to expand the set of bidders when it finally turns to privatising some of our public sector banks", which they strongly oppose ("Indian Banks: A Time for Reform?") and secondly, "an industrial house holding a payment bank license wants to transform into bank" since one of the IWG recommendations is to shorten the time for such transformation from five to three years.

The first answer gives a clue to an equally big banking reform waiting in the wings: handing over ownership of public sector banks to private corporates/industrial houses. Indeed, the government has disclosed that it intends to give up ownership of more than half of public sector banks (PSBs).

That the banking system has been in severe crisis for several years is not unknown.

A number of banks and NBFCs have collapsed and/or are facing serious charges of financial mismanagement involving many corporate bigwigs of India since 2018: PMC Bank, Punjab National Bank, ICICI Bank, Yes Bank, Lakshmi Vilas Bank, IL&FS, HDIL, DHFL (last three being NBFCs) etc.

The crisis is mainly due to loan defaults (NPAs) by corporate entities and poor corporate governance that allow undue favours, diversion of loans to projects not meant for and money laundering. Some of the big corporate leaders like Vijay Mallya, Nirav Modi, Mehul Choksi, Jatin Mehta (Winsome Diamonds) and Sandesara brothers (Sterling Biotech) are accused of misdeeds and have fled the country without paying their debts.

The Credit Suisse's "India Corporate Health Tracker" of August 2019 showed that barring a few exceptions, all big private business houses are heavily indebted and "chronically stressed". It warned that another wave of NPA crisis is coming. (For more read "Rebooting Economy XIII: Why Indian corporates are debt-ridden ")

That was before the pandemic hit.

The pandemic brought moratorium on loan repayment, which big businesses lapped up even when capable of repaying. The RBI's half-yearly Financial Stability Report (FSR) of July 2020 said 70% of the moratorium offer was availed by corporates rated 'A' and above with comfortable debt-equity ratio (meaning they could pay but chose not to).

This RBI report warned that the Gross NPA ratio of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) was likely to worsen from 8.5% in March 2020 to 12.5-14.7% in March 2021 due to the pandemic-induced economic distress.

The IWG's main argument for allowing big corporates/industrial houses to run banks is that India's credit-to-GDP ratio is very low, just about 50% in 2019, while that of the US, Japan, China and South Korea was more than 150%.

At 50% of credit-to-GDP, the Indian banking system has slipped into deep financial distress. What would happen when the lending goes up to 100% or 150% that the RBI's IWG seeks?

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 46: Who is designing India's growth path?

Also, who will take additional liquidity to be generated?

Certainly not large industries as the RBI data reveal they have had very poor credit growth in the past few years. In FY20, the credit growth to large industries plunged to 0.6% and to industry as a whole (small, medium and large) a meagre 0.7%.

In case the IWG and RBI are constrained for funds, here is an efficient and abundant source of it.

India has a very vibrant and booming capital/stock market with more than enough liquidity the RBI can tap any time. Even as the Indian economy has slipped into a recession and performed worse than all major economies in the world, its stock markets have touched new highs.

On November 24, 2020, the BSE Sensex touched an all-time high of 44,523 (daily closing) - overtaking by a mile its pre-pandemic high of 42,063 of January 17, 2020. The same day, the Nifty50 crossed its pre-pandemic high of 12,362 recorded on January 14, 2020 by breaking a new record of 13,055 (daily closing).

Who is behind this reform proposal?

Why did the IWG make such a proposal amidst a banking crisis caused by corporate loan defaults, money laundering etc. and recession?

It gives an important clue.

It says: "All the experts except one were of the opinion that large corporate/industrial houses should not be allowed to promote a bank."

It spelt out their objections too:

1. Primarily because "prevailing corporate governance culture in corporate houses is not up to the international standard";

2. "It will be difficult to ring fence the non-financial activities of the promoters with that of the bank" and "stress in non-financial activity may spill over to the bank;

3. Corporate houses "may either provide undue credit to their own businesses or may favour lending to their close business associates";

4. "May influence lending by the bank, to finance the supply and distribution chains and customers of the group's non-financial businesses" and

5. "There are various ways of circumventing the regulations on connected lending and due to complex structures of entities, cross holding of capital, the disbursal/diversion of funds to group concerns is difficult to check".

Several questions arise from these: If all the experts it consulted, except one, opposed the proposal, why did IWG go for it? What new evidence has it got to over-turn the RBI's earlier stand (most recently in 2020 and 2016) and negate two Parliamentary Standing Committees of 2013 and 2014 which strongly opposed it? Who is driving the RBI from backrooms?

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 45: What is AatmaNirbhar Bharat and where will it take India?

First, here is some insight that Rajan and Acharya provided in their article.

They wrote that the IWG "may have had little power over" this recommendation and explained that this could be the reason for the IWG to suggest "significant amendments to the Banking Regulation Act of 1949" before allowing big corporate players to own and run banks. They went on to puncture this fatuous pre-condition by arguing that had legislation been the answer, corporates wouldn't have misused the banking system and the NPA crisis wouldn't have arisen in the first place.

Secondly, a couple of months back in August 2020, national dailies reported that the RBI had shot down the Niti Aayog's proposal to allow big corporates/industrial houses to set up and run banks.

This was not surprising since the central bank had junked such a suggestion in 2016 also while issuing "Guidelines for 'on tap' Licensing of Universal Banks in Private Sector". The document categorically stated that "large industrial houses are excluded as eligible entities", even while allowing them to invest up to 10% in banks.

This was a change in position for the RBI from its 2013 stand spelt out in the guidelines for banking licenses, which had allowed industrial houses to apply for banking licenses. What made it change its stance?

Two Parliamentary Standing Committees, one in 2013 and another in 2014, were scathing in their criticism of the RBI's 2013 move, pointing at facts and evidence to recommend that banking being "a highly leveraged business involving public money and public welfare" it will be more in the fitness of things to "keep industry and banking separate".

The 2014 committee reminded the RBI and the government that the presence of bank branches in rural areas is very low (17%) and most banks - 6 of 26 private banks and 16 of 26 public sector banks - had failed to comply with 40% priority lending norm.

It concluded: "The Committee, therefore, reiterate that the Government/RBI should ensure that no recurrence of the pre-nationalization situation happens, when the management of private banks deployed their funds to extend undue favour to their own industrial owners without regard to social priorities determined by Government."

What did it mean by "no recurrence of pre-nationalisation situation" and why did it warn about it?

Forgotten lessons of Bank Nationalisation of 1969

Why banks were nationalised, starting with 1969, is instructive.

Until 1969, Indian banking was entirely in private hands.

The RBI recorded that historical transition from private to public ownership (some private banks were allowed to operate even then) in the first chapter "The Defining Event" of Volume III (1967-1981) of its own history - "RBI History".

Here it goes.

The report said there were several political, economic and banking compulsions at the time. India faced political uncertainties following the deaths of the first two Prime Ministers, Nehru and Shastri, within a short span of two years. The 1962 war with China and the 1965 war with Pakistan, drought and famines caused immense economic stress: the treasury was empty and a balance of payment crisis hit, delaying the Third Five-year Plan by three years.

As for the banking reasons, it listed three: (a) lack of banking facilities for (i) agriculture (ii) small-scale industrial units and (iii) self-employed (b) bank expansion during 1951-1967 "un-served" rural and semi-urban areas as focus was firmly on urban areas and (c) private banks were "seen as being excessively concerned with profit alone" and "unwilling to diversify their loan portfolios".

Under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the Congress sought to remove such distortions by declaring in its 1967 election manifesto that "it was necessary to bring most of the 'banking institutions under social control to serve the cause of economic growth more effectively and to make credit available to the producers in all fields where it is needed'".

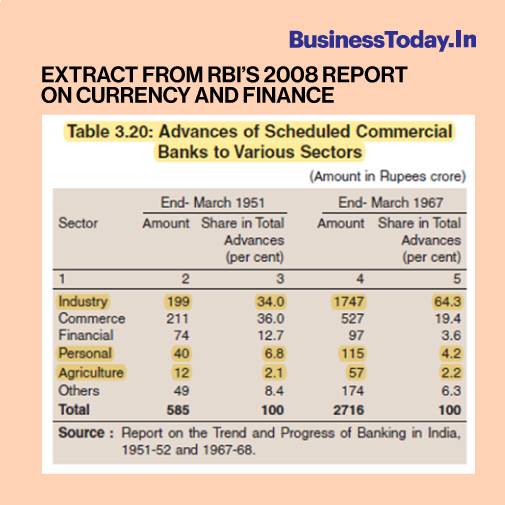

The following two graphs have been taken from the RBI's 2008 "Report on Currency and Finance" to reflect the ground realities of the time.

The first graph shows the share of credit flows to agriculture was a meagre 2.1% in FY51 and marginally improved to 2.2% in FY67; that to individuals ("personal") went down from 6.8% in FY51 to 4.2% in FY67. On the other hand, the share of credit to industry was a high 34% in FY51 and grew even higher to 64.3% in FY67.

As on March 27, 2020, the situation was different.

The share of credit flow to agriculture had increased to 12.6%, that for "personal" loans to 27.7% and industry's share stood at a healthy 31.5% (large industries accounted for 26.2% of the total) - according to the RBI database.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 43: States exhaust MGNREGS fund, leave Rs 1,386 crore in unpaid wages

This is a massive redistribution of credit, particularly to the unbanked population.

The next graph shows distribution of bank branches.

Rural branches were fewer - 13.3% in 1952 (end December), growing to 17.9% in 1967 (end December). Urban/metropolitan branches were 35.7% in 1952, growing to 38.9% in 1967. Semi-urban areas saw its dominance coming down from a high of 47.8% in 1952 to 43.3% in 1967.

At the end of June 2020, the RBI database showed the number of commercial bank branches stood at 33.3% in rural areas, 27.4% in semi-urban and 39.3% in urban/metropolitan areas.

That is a massive improvement too.

How did nationalised banks save India during 2007-08 crash?

The Great Recession of 2007-08 taught a big lesson to all economies: private and largely unregulated banking and other financial institutions (particularly NBFCs) pose a serious systemic risk. Complex, opaque and high-risk financial instruments that private banks, NBFCs and other financial entities brought in to maximise profits derailed the US economy, and the distress travelled across the world.

India emerged relatively unscathed because its banking system is dominated by government-owned banks with less opaque and risky instruments of maximising profits. The US paid a heavy price of bailing out its financial system. It nationalised two big shadow banks (NBFCs) in the housing mortgage markets, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. By then they had run up a combined debt of $5.4 trillion.

Ironically, Fannie Mae was a government-owned entity, set up in 1938 to fight the financial crunch in the wake of the 1929 Great Depression (sparked by private financial entities) and had a highly successful run for 30 years when it was handed over to the private sector in 1968. Freddie Mac was created by the US Congress too, but as a private entity to compete with Fannie Mae. Both put a burden of $5.4 trillion on the US taxpayers when these were nationalised in September 2008. (For more read Rebooting Economy XVI: How governments run shadow banking and risk financial stability)

The US government also bailed out several other private banks and financial institutions, namely Bank of America, Citigroup, AIG, Bear Stearns, at a huge cost to its taxpayers.

India did not have to do it then but it should be prepared before following the same path that led to multiple economic crises all over the world from 1929. Apart from the Great Recession of 2007-08, financial mismanagement by private banks, NBFCs and other financial entities led to the dot.com burst (2000-01), Asian financial crisis (late 1990s), Latin American crisis (1990s-2000s), Japan crisis (1990s-2000s) and many others. (For more read "Rebooting Economy XII: Is private sector inherently more efficient than public sector? ")

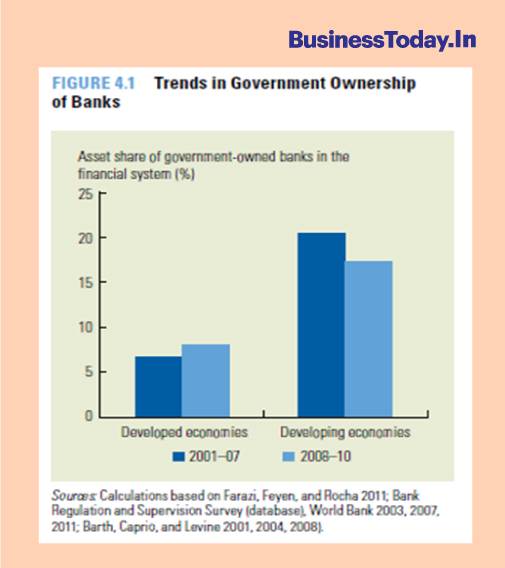

The Great Recession of 2007-08 brought some dramatic changes in banking systems in developed countries. They are now increasing government-ownership (asset share) in banking.

Here is a graph from the World Bank's 2013 report "Rethinking the Role of the State in Finance" showing the changes in government-ownership in banking pre- and post-2007-08 financial crisis.

Developed economies have increased government ownership in banks (asset share) but developing ones like India are diluting theirs, which indicates the latter countries are not learning any lesson.

This World Bank report clearly explained why and how government-ownership of banks are critical in "stabilising aggregate credit" and played key roles in limiting damages during the financial meltdown of 2007-08 in several countries, including India and China. (For more read "Rebooting Economy XVII: Why governments promote shadow banking ")

No wonder, many developed countries, including the US, keep banking and other industries separate. The US specifically prohibits big industrial houses with ownership and controlling stakes in non-banking business (manufacturing and others) from owning or controlling banks.

India will do itself great harm by diluting government-ownership that saved it from the 2007-08 global financial meltdown.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 42: How will changes to land laws in Jammu and Kashmir help, and whom?

Will "bail-in" reform be the next?

Allowing big corporates/industrial houses to own and run banks and handing over ownership from government to private are not the only two big-ticket banking reforms in the pipeline. A third one has been in cold storage since 2018, following a huge uproar, but the possibility of its comeback can't be written off (labour reforms were put off in 2017 to be brought back in 2019 and 2020 and passed in a hurry).

That pending bank reform is "bail-in" provision in the Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance (FRDI) Bill of 2017, which proposed (Clause 52) that in case a bank fails the depositors' money will be used to bail it out (as one of the resolution tools).

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 41: India's growing poverty and hunger nobody talks about

What it means is that the depositors of such a bank will pay with their deposits to revive failed banks. Until now, public depositors and taxpayers have been bailing out banks by way of NPA write-offs and remonetisation of banks. This is an additional incentive to big corporates/industrial houses to own and run banks with public deposits. Rather, the fourth "win" for them and the "fourth "loss" for depositors and taxpayers.

Insurance cover for bank deposits has been raised from Rs 1 lakh to Rs 5 lakh in the 2020 budget, which means in case a bank fails, the depositors are protected up to a maximum of Rs 5 lakh. The rest will be lost to "bail-in" for bailing out failed banks in case this reform is revived.

Why "authoritarian cronyism" is a threat?

While warning about "authoritarian cronyism", Rajan and Acharya omitted a few things.

The stage for such an eventuality was set with the introduction of opaque Electoral Bonds in 2017. It has opened a floodgate of unlimited and unaccounted money from anonymous corporates to donate to political parties.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 40: Why Punjab farmers burn stubble?

Additionally, Electoral Bonds are out of legal scrutiny and disclosure norms. The Representation of People Act of 1951 has been amended to keep corporate donations through Electoral Bonds out of the scrutiny of Election Commission of India (ECI) and The Companies Act of 2013 too has been amended to remove limits on such corporate donations and disclosing the name of the political party to which such donations are being made. No wonder the ruling party is getting most of Electoral Bond donations.

In September 2019, amidst the pre-pandemic economic slowdown, the government cut corporate tax by Rs 1.45 lakh crore, even while facing difficulty to honour GST compensation payment commitment. (For more read "Rebooting Economy XXIV: 7 critical GST flaws govt needs to address at the earliest "). Instead of using tax cuts to invest and generate jobs as the people were told, corporates went for "debt servicing, build-up of cash balances and other current assets rather than restarting the capex cycle", as the RBI's Annual Report, 2019-20, later revealed.

Enough has already been written about the fresh leash of life to crony capitalism in India in recent years (most lucrative projects landing with two industrial houses close to the government) to warrant elaboration.

Enough is also known (from history) about how a cocktail of crony capitalism and a regime with poor democratic instincts can overrun any society or country.

No comments:

Post a Comment