Indian agriculture is lagging in growth compared with the rest of the economy for decades. Here is why it is time to rewrite the policies to provide fresh impetus to agriculture growth.

- Prasanna Mohanty

- New Delhi

- December 17, 2020

- UPDATED: December 18, 2020 11:41 IST

The current stand-off with farmers and the frequent farmers' agitations in the past few years reflect an ad-hoc approach to policymaking for such a critical sector that provides jobs to more than 40% of India's total workforce and sustains nearly 70% of its rural population but generates very little income.

In FY20, agriculture's share of the country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (national income) was just 14.65 per cent - down from 22.6 per cent in FY05 (the years for which the 2011-12 GDP series provides data). The sector grew at an average annual rate of 3.6 per cent while that of the economy was 6.7 per cent during this period.

A closer look at the state of agriculture shows virtually every aspect of it -- from factors of production like land, labour and capital to marketing, trade and protections against crop loss - calls for a comprehensive review and reframing of policies.

First, here is what the agriculture statistics reveal.

India has more farm labourers than farmers

The 2011 Census showed, for the first time, landless agriculture labour outnumbered cultivators in the agricultural workforce - which consists of these two categories of workers. They constituted 55 per cent of the workforce and numbered 144.3 million, as against 45 per cent or 118.8 million of cultivators.

It is tough to drive or sustain growth in agriculture since farm labourers get no policy support or incentive to invest in farming.

All benefits like seed kit, fertilisers, pesticides, farm machinery, micro-irrigation, land development assistance etc. are meant only for those who can prove land ownership.

All cultivators are not necessarily farmers though. Absentee landlordism is rampant and landless farm labourers double up as tenant farmers, sharecroppers or leaseholders and do the actual farming.

Several government-appointed bodies, like the National Commission on Farmers (NCF) of 2007 and the Ashok Dalwai Committee of 2017, have recommended that they be treated as farmers and all benefits be extended to them but to no avail.

Agriculture landholding shrinking rapidly

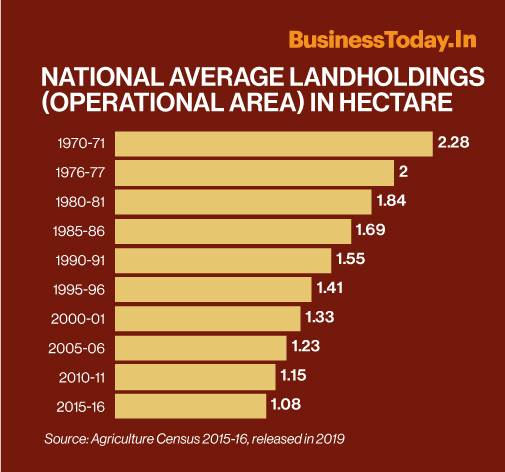

At the national level, the average size of agriculture land has shrunk from 2.28 hectare in 1970-71 to 1.08 hectare in 2015-16 - far lower than that of Australia (4,331 ha), Canada (315 ha), the US (180 ha) and the EU (16 ha).

The trend in the distribution of land is even more alarming - as the following graph show.

The number of marginal and small farmers (less than 1 ha and less than 2 ha, respectively) continue to remain very high (more than 85 per cent of all farmlands). There is a dramatic rise in the number of marginal farmers and equally dramatic fall in that of farmers with bigger landholdings (more than 2 ha).

Punjab and Haryana forming the "food baskets" of India are at the top. The average landholding in Punjab is 3.6 ha, while that of Haryana (number 3) is 2.2 ha. Rajasthan, the home of the Thar Desert, is second with 2.7 ha.

Various policy responses like promoting farmer producer organisations (FPOs) and contract farming through land-pooling have not achieved much for small and marginal farmers in the past few decades. The Dalwai Committee had even warned that global experience showed contract farming has not attracted small and marginal farmers.

Taken together, the landless, small and marginal farmers constitute 93.7 per cent of the total agricultural workforce. Without their welfare agriculture can't grow.

Investment in agriculture going down

Investment is the key to growth. Given the limited fiscal space, Indian governments have been promoting private investment. The Dalwai Committee had recommended in 2017 that for doubling farmers' income by 2022-23, an additional investment of Rs 6.39 lakh crore would be needed.

The statistics, however, show a different trend.

The gross capital formation (GCF) in agriculture as a percentage of the total GCF in the economy has fallen from 8.5 per cent in FY12 to 6.5 per cent in FY19. This is because the share of private investment has shrunk. Though public investment has gone up it is not sufficient to check the slide or keep the GCF at FY12 level.

Short-term crop loans growing, long-term investment loans falling

This is not the only worry. More of the capital deployment in the sector is for immediate needs of farming, rather than long-term investment for growth (land development, technologies, research etc.).

The RBI's "Report of the Internal Working Group to Review Agricultural Credit" released in September 2019 said the credit outflow to agriculture is more and more for immediate cropping needs. Long-term credit for investment is rapidly falling - as the graph reproduced from this report demonstrates.

This report found widespread diversion of agriculture credit (lower interest rate, interest subvention and rebates for timely payment) to non-agriculture. There are regional disparities too with central, eastern and north-eastern states getting a far lower share of institutional credit than north, western and southern states.

The RBI suggested changes in the Priority Sector Lending (PSL) guidelines to address some of the issues but that clearly is not adequate. The failure to attract private investment needs to be understood and scrutinised first to affect change.

Failure of market to give farmers a fair price

That the private market has failed farmers is well known and is at the centre of the current stand-off between the farmers and the government.

The statistics relating to government procurement of wheat and rice (two primary items procured) at the minimum support price (MSP)-based system that operates in state government-run APMC mandis show farmers prefer this to private markets.

The following graph shows the quantum of wheat and rice (milled paddy) procured in million tonne (MT) and the percentage of the total production of wheat and rice that is being procured. Both numbers are going up.

Had private markets been fair to farmers, they would not be holding frequent protests to seek higher MSP or a legally-binding guarantee of MSP in private trade, as they are demanding now.

Export of agriculture and allied products going nowhere

If markets have failed farmers, the government's tight regulations on trade and uncalled-for interferences (onion export was banned in September even when the price rise did not reach the level to trigger such a ban that one of the three new farm laws mandates) has imposed additional costs.

The following graph maps the growth in export of agriculture and allied products like rice, coffee, tea, tobacco, spices, oilseeds, fruits and vegetables, cereal preparations and miscellaneous processed items, meat, dairy and poultry products etc.

No growth is visible.

Farmers and farm areas under crop insurance likely to shrink further

There is yet another problem. Crop insurance schemes to protect farmers from crop losses are failing.

India introduced two new crop insurance policies in 2016 to expand the coverage of farmers and farm areas - Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) and Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) - which opened up space for private insurance companies in a big way.

The new schemes seemed to work well in the first year by expanding the coverage but soon state governments and farmers started pulling out for various reasons like delayed or denial of compensation and profiteering. In many cases, insurance companies have paid substantially less than the premium they received from farmers and governments. Farmers pay 1.5% to 5% of the sum assured and the rest is paid equally by the central and state governments.

Bihar was the first one to pull out to launch its own scheme. West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh have taken the same route.

In the graph above, the slide has been reversed for the Kharif season of 2019 (part of FY20 and marked 2019 K in the above graph) and yet there is a reason to expect a continued slide because in February 2020, the central government made crop insurance voluntary. Until now it was compulsory for all those who applied/received bank loans.

Dialogue and deliberations to fix policy issues

India's national agriculture policy is 20-years-old. It needs a revisit to fix many of what ails the sector now.

Democratic norms and processes like open public debate, dialogue with stakeholders and detailed Parliamentary scrutiny to ensure every aspect and implication of a public policy goes through meticulous examination before being adopted and implemented is crucial to fix those.