First published on Sept 21, 2020

Contrary to Centre's claims, a parallel private market for farm produce and negation of states' regulatory power are aimed at helping private businesses at the cost of farmers. The last thing distressed farmers need is exposure to unregulated market forces

Prasanna Mohanty | October 4, 2020 | Updated 16:17 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | October 4, 2020 | Updated 16:17 IST

On July 23, Prime Minister Narendra Modi invited US companies to invest in Indian agriculture (and healthcare) under the Indian flagship programme 'Atma Nirbhar Bharat' (self-reliant India), while addressing the USIBC India Ideas Summit. He listed the areas of opportunities-agriculture inputs and machinery, agriculture supply chain, food processing sector, fisheries and organic produce.

He also talked about India's recent reforms, apparently referring to three ordinances the Centre had issued on June 5, 2020, amidst the lockdown, without consulting the state governments or farmers and without a plan in place - the trademark style of governance the Centre has adopted in past six years.

The three agriculture-related legislations are The Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Ordinance, 2020; The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020 and Essential Commodities (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020.

The first two were passed by Rajya Sabha via voice vote on Sunday while Lok Sabha had passed all three earlier.

Also Read: Farm bills undermine 3 pillars of food security system -- MSP, public procurement, PDS: Chidambaram

Ironies of agriculture reforms

The ironies in the Centre's moves are too many and too obvious to miss.

The first is the Prime Minister's appeal to American companies to make India "Atma Nirbhar" or self-reliant in agriculture.

The second is the Centre's promise of "empowerment", "protection" and "promotion" of farmers (these words have been used in the ordinances), but farmers of at least three states, Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, have hit the streets to protest, saying these bills are designed to harm their interest and promote that of private businesses.

This is not the end of ironies.

'Freedom of choice' and 'empowerment' of private businesses, not farmers

The most contentious move is The Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020, introduced on September 14 to replace the corresponding ordinance. Its stated objective is to provide "freedom of choice" to farmers to sale "outside the physical premises of markets or deemed markets" so as to facilitate "remunerative prices" through "competitive alternative trading channels".

For this, Clause 6 of the bill says: "No market fee or cess or levy, by whatever name called, under any state APMC Act or any other State law, shall be levied on any farmers or trader or electronic trading and transaction platform for trade and commerce in scheduled farmers' produce in a trade area."

The implications of this clause are clear: (i) create aparallel private marketto about 2,500 state government-run APMC mandis operating in India since "scheduled farmers' produce" refers to farm produce traded in APMC mandis (one nation two markets, instead of "one nation one market" credo of the Centre) and (ii) usurp states' power (agriculture is a state subject) to deliver another blow to "cooperative federalism" soon after the GST fiasco (unresolved yet).

Here is yet another irony.

The Shanta Kumar committee set up by the current dispensation said "only 6 per cent of total farmers in the country have gained from selling wheat and paddydirectly to any procurement agency". That is, through state government-run APMC mandis, only 6% of Indian farmers sold their produce to government procurement agencies.

This report came in January 2015, but this is the latest official update on the subject and its source is the NSSO's 70thround of survey capturing 2012-13 data.

What it means is that 94% of farmers are already enjoying "freedom of choice" and trading with private companies and traders through APMC mandis or outside. If the rest 6% farmers so desire they can join the majority. Nothing stops them.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVIII: Is India poised for agriculture-led economic turnaround?

Why is the move then?

The answer is in Clause 6 quoted above: no market fee, cess or levy would be charged in the parallel private market, operating outside the regulated state-government-run APMC mandis.

This fee is charged to private companies and traders who buy agriculture produce at APMC mandis, not farmers. Removing it will directly benefit them. On the other hand, funds collected through this fee are used for maintaining and improving APMC facilities and helping farmers when needed. Thus, removing the fee will harm farmers.

There is another critical issue.

Who will set up the parallel private market? The bill is silent on this.

State governments wouldn't do (they run APMC mandis) and the Centre can't as it is a gigantic task and may take another 70 plus years. Apparently, it will be left to private companies and traders. Will farmers get a fair price for their produce in unregulated private mandis? Who and what will empower them?

The APMC system has many flaws, like commission agents or arhatiyas in Punjab and Haryana mandis who take a cut from farmers' earnings and exploit them in various ways (they also help with loans, seeds and other supports and guarantee buying their crops), which need to be eliminated but the bill does not do so.

Here is one more irony.

Instead of removing these commission agents, the bill defines 'trader' in such a way (a person who buys farmers' produce for self or on behalf of others for further trade and use) that it legitimises them and paves their entry into rest of the country's agriculture markets.

Another major shortcoming of the APMC system has been its failure to ensure fair and remunerative prices to farmers outside the procurement operations. Procurement is limited mainly to wheat and paddy (small amounts of soya bean, cotton etc. are also procured by some agencies at times) while the minimum support price (MSP) is announced for 23 crops every year.

Other farmers who sell their produce in APMC mandis outside the procurement operations don't get MSP prices because mandi prices are often lower. These are not addressed in the new reform measures either.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVII: Fiscal mismanagement threatens India's economic recovery

Farmers' income won't double through unregulated mandis

The very purpose of government-mandated MSP and procurement operations is to ensure farmers get a fair and remunerative price for their produce. Had open markets been fair to farmers, there would have been no need for this. Farmers wouldn't be hitting the streets almost every year to demand higher MSP to cover rising cost of production (input costs have risen sharply in recent decades).

The parallel private markets will have nothing to do with MSP operations. The MSP is not even mentioned in the bill or any other ordinance.

The other ordinance relates to contract farming - The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020 - and says farmers will negotiate "mutually agreed remunerative price" or the "guaranteed price".

For "any additional amount over and above the guaranteed price", it says, a reference can be made to "prevailing prices in specified APMC yard or electronic trading and transaction platform". This "prevailing price" is, more often than not, below the MSP prices.

Former agriculture secretary Siraj Hussain writes that even in contract farming farmers get substantially lower than market prices. Giving the example of poultry in India, where contract farming is a success (66% of production in contract farming) he writes that a study found non-contract farmers' net return was Rs 17.05 per bird (broiler) against a mere Rs 11.06 for contract farmers.

Though contract farmers are shielded from risks of diseases (care is provided by aggregators) and market fluctuations (prices are pre-fixed), he warns that "even in the US, contract farming of poultry has benefited producers more than the poultry farmers".

For crops for which MSP is announced, Hussain points out that organised players are "generally reluctant to sign agreements as they are not sure if the states will hold them accountable if the agreed price is below MSP".

So, the chances of farmers getting MSP or fair price in the parallel private market are very slim.

Here is a 2018 example of the extraordinary power of private companies and traders operating within state government-run APMC mandis.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVI: Derailment of economy is not 'Act of God', it is 'Art of Misdirection'

After the Centre raised minimum support price (MSP) that year following two years of farmers' agitations all over the country, the market prices for both rabi and kharif crops crashed. In October that year, prices of all kharif crops crashed across more than 1,700 APMC mandis simultaneously.

It would be naive to expect non-regulated parallel private market to give a fair price to farmers or help in doubling their income, as the Centre has been promising for years.

Usurping states' power and disabling states' oversight harmful for farmers

The new reforms usurp state governments' power to regulate agriculture produce markets.

In addition to Clause 6, Clause 3 of the Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020 removes states' role in inter-state and intra-state trade; Clause 12 empowers the Centre to issue any instruction to state government and its authorities regarding parallel private markets and Clause 14 overrides all state laws related to agriculture marketing.

The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020 allows farmers to have written agreements with private players for which the Centre will issue guidelines.

Clause 7(1) of this ordinance takes away state government's power saying that such a contract will be "exempt from the application of any State Act, by whatever name called". Clause 7(2) says restrictions on stock piling/hoarding under the Essential Commodities Act of 1955 will not apply to such contracts, thereby, disempowering states in case of hoarding and profiteering by private players.

Since the third ordinance, Essential Commodities (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020, mandates that stock limits (hoarding) will be regulated "only under extraordinary circumstances which may include war, famine, extraordinary price rise and natural calamity of grave nature", insertion of Clause 7(2) is redundant, but its presence shows there could be more to what meets the eye.

Further, the role of state and judiciary in dispute resolution has been diluted.

The contract farming ordinance bars jurisdiction of civil courts (Clause 19) to disputes. It provides for private resolution mechanism which can be scaled up to a sub-divisional magistrate and collector but the latters' resolution can't be challenged in civil courts.

Absence of penalty for violations of contract further weakens the farmers' interest in case a private player refuses to honour its commitment.

All this leaves farmers even more vulnerable to exploitation.

Such unthinking and unilateral measures by the Centre have created a panic among farmers that it may eventually dismantle MSP and procurement operations. Consumers also stare at the potential hoarding and profiteering as restrictions on stock piling have been eased.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXV: How a series of economic misadventures derailed India's growth story

Even US doesn't leave farmers at the mercy of market forces

Here is some food for thought.

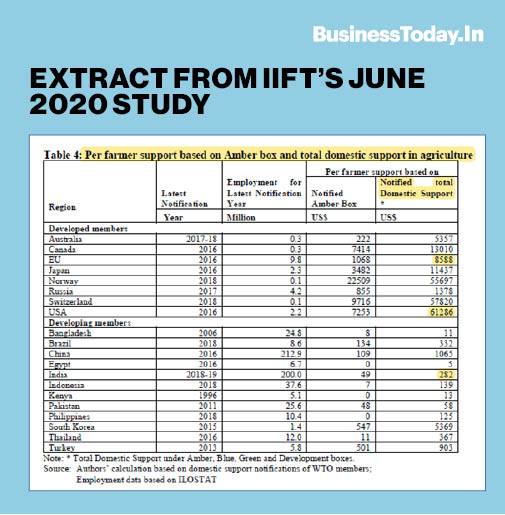

Dr. Sachin Kumar Sharma, Associate Professor of the Centre for WTO Studies, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade (IIFT), says: "The US, although a firm believer of free market, does not leave its farmers at the mercy of market forces. Rather, it provides huge support to farmers in the form of price support, direct payments and insurance subsidy programmes, among others. For instance, the level of per farmer support in the US is more than 200 times of what the Indian farmers receive."

Dr. Sharma is the principal author of a study, "Revisiting Domestic Support to Agriculture at the WTO: Ensuring a Level Playing Field", published by the IIFT in June 2020.

This study gives a comparative picture of subsidies given to farmers by the US, India and other countries (subsidy "per farmer"). The US spends $61,286 (or Rs 45 lakh at exchange rate of Rs 73) on each farmer a year, while India spends a paltry $282 (Rs 20,727) a year.

There is another table in this study, which shows the average landholdings of farmers in the US, India and other countries.

The average farm holding of the US farmers is 180 ha and that of Indian farmer 1.08 ha.

Even with such high government spending and high average landholding, the US farmers are distressed: their income is falling, indebtedness and bankruptcy rising and they are seeking more fiscal support due to the pandemic-induced economic disruptions.

Here is how their income level has moved, taken from a February 2020 (pre-pandemic) paper, "A Tale of Two Farm Incomes", published by the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) using the US government data.

Does it make any sense for the Indian government then to take away state governments' control over marketing of farm produce, expose farmers to unregulated private markets, create panic over the future of MSP and procurement operations and also expose consumers to the risk of black marketing and profiteering by private businesses?

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXIII: What stops India from taking care of its crisis-hit workers?

No comments:

Post a Comment