Rural economy is struggling with job and income losses, the true extent of which are not known since India isn't tracking or compensating; credit and liquidity risks to small businesses and crop loss due to excess rain

Prasanna Mohanty | September 25, 2020 | Updated 20:45 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | September 25, 2020 | Updated 20:45 IST

The rural economy may be in a far deeper crisis than what the Q1 of FY21 data indicates. Though the agriculture sector is the only one showing positive growth of 3.4% growth in GVA (all others being negative), there are other indicators which show a massive impact of the lockdown.

The central bank RBI's September 2020 bulletin (released on September 11) warns of a big risk to the microfinance sector, which majorly supports income generation and livelihood in rural areas.

High risks to small businesses in rural India

As for the risk to the microfinance sector, the RBI bulletin says: "COVID-19 event is perhaps the biggest tail risk event in a long time. Owing to the disruptions in supply chain and business operations, the likelihood of loss of livelihoods and consequent drop in household incomes is high."

Small traders, hawkers and daily wage labourers, who constitute a large chunk of microfinance borrowers (primarily self-help groups, a significant number of which are run by women), "were the worst hit by the lockdown in April 2020". This category of employment accounts for 32% of the total employment but "suffered 75 per cent of the hit in April 2020".

Also Read: Economy XXIX: Exposing farmers to unregulated market is more likely to harm them

The collection efficiency (loan recovery) of microfinance institutions (MFIs) fell sharply to 3% in April 2020, recovered to 21% in May and 58% in June but remains far lower than 83% recorded in March 2020 (lockdown started on March 25). A "significant proportion" of such borrowers have availed moratoriums on loan repayments.

The outstanding MFI loans stood at Rs 2.32 lakh crore on March 31, 2020 - up from Rs 1.79 lakh crore on March 31, 2019.

The graph below shows how microfinance collections have been impacted.

The RBI report further says the NBFC-MFIs "are particularly exposed to credit risks". These NBFC-MFIs specialise in providing collateral-free loans to low-income groups and are concentrated in rural areas (75% of loan portfolio) with a majority of loans to agriculture and allied activities (55.8%).

The RBI considered two stress scenarios for NBFC-MFIs - 40% and 80% drop in recovery - and found that the gap between inflows and outflows (outflows assumed constant in both scenarios) narrowed down in the first scenario (40% drop) but still remained positive across time periods (spanning 1 month to 1 year). But in the second scenario (80% drop), the cumulative gap up to 6 months and up to 1 year "turned negative", indicating "need for additional funding".

Growing NPAs in MUDRA loans

In the meanwhile, MUDRA loans are also in trouble.

These are (loans up to a maximum of Rs 10 lakh) also collateral-free and given to non-corporate small businesses, mainly MSMEs.

A news report quoting finance ministry data says that loans from PSBs alone have gone up from Rs 2.12 lakh crore in FY18 to Rs 3.05 lakh crore in FY19 and Rs 3.82 lakh crore in FY20).

At the same time, their non-performing assets (NPAs) have progressively risen - up from Rs 7,277 crore (3.42%) in FY18 to Rs 11,483 crore (3.75%) in FY19 and Rs 18,835.77 crore (4.92%) in FY20.

Although the rural component of these loans is not known, 51% of MSME units are located in rural areas. As a relief measure, on June 24, 2020, the Centre announced an interest subvention of 2% only to Shishu loans (up to Rs 50,000) for a year.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVIII: Is India poised for agriculture-led economic turnaround?

Growing NPAs in MUDRA loans would lead to more risk-averse behaviour from the lending institutions, thereby creating liquidity crunch.

Any trouble with MUDRA and other microfinance (MFIs) loans would seriously impact the rural economy, both farm and non-farm activities.

The NABARD's Rural Financial Inclusion Survey of 2016-17, released in August 2018, showed that even in agriculture households (constituting 47.5% of 211.6 million rural households), only 35% of the average monthly income (of Rs 8,931) came from cultivation and the rest from other activities. Among non-agricultural households, 54% of the average monthly income (Rs 7,269) came from wages, 32% from salaries and 12% from non-farm sector activities.

These income calculations excluded income from transfers and remittances.

Remittances from urban areas disrupted

Remittances from migrant workers boost the income of rural households, which dried up as millions lost their jobs overnight. The government's reply to the Lok Sabha revealed that 10.4 million migrants went home, mostly to rural areas.

Migrants send home Rs 2 lakh crore a year, a national daily quoting financial service companies reported. It further said that immediately after the lockdown, these companies recorded 80% drop in remittances in April 2020.

In September 2020, a joint study by the London School of Economics and Political Science, "City of dreams no more: The impact of Covid-19 on urban workers in India" found that (i) 52% of urban workers went without work or pay and received no financial assistance and (ii) on average, earnings fell by 48% in April and May, compared to pre-pandemic months of January and February with financial assistance available to less than 25% of the workforce.

The study does not talk of migrant workers or remittances but the likelihood of these urban workers remitting money to rural India can't be ruled out entirely.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVII: Fiscal mismanagement threatens India's economic recovery

How many migrant workers lost their jobs or died while walking home during the lockdown is not known. The government told Lok Sabha on September 14 that it did not track either.

A private initiative by citizens recorded 906 non-virus deaths during the lockdown (from exhaustion of walking home hundreds of miles, starvation, accidents etc.)

The net result of non-tracking of job loss and death by official agencies makes it difficult to know the true extent of rural distress.

Excess rain and spread of COVID-19 to rural areas

Two disturbing news have come in the meanwhile.

One, reports from states producing significant Kharif crops like Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Telangana, say that excess rain in August-end caused extensive damage. Sowing of Kharif may have gone up by 8.5% in area but excess rain can ruin the gains.

Two, the COVID-19 cases are rapidly growing in rural areas. From 24% in April, rural districts contributed 51% in July and 55% in August to new virus cases, says an SBI research paper, "Three Months After Unlock", released on September 3, 2020. (For more read "Rebooting Economy XXVIII: Is India poised for agriculture-led economic turnaround? ")

Given that rural healthcare facilities are worse than urban ones, the spread of the virus would take a heavier toll on livelihood activities and income in rural India than in urban India.

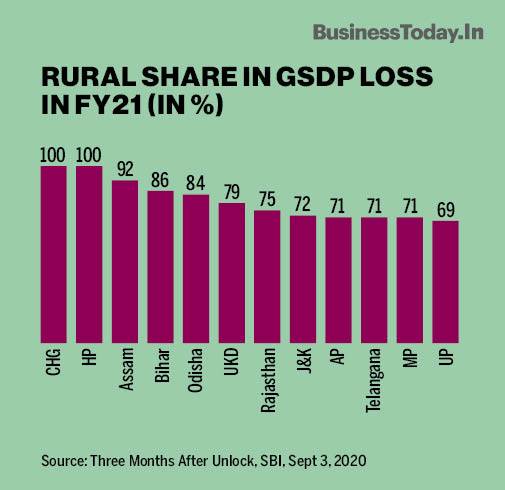

This SBI research also showed how Q1 of FY21 saw high rural loss, even though the overall agriculture GVA recorded a positive 3.4% growth. At least 12 states showed the rural share in GSDP loss between 69% and 100% - as reproduced below.

These states are major producers of rice, wheat, sugarcane, potato, chickpea, groundnut, maize, soya bean, coarse cereals and pulses, the report pointed out.

Rural economy contributes significantly to national output and employment

The threats to credit and liquidity crunch and those from excess rain and virus cases would seriously impact national output and employment.

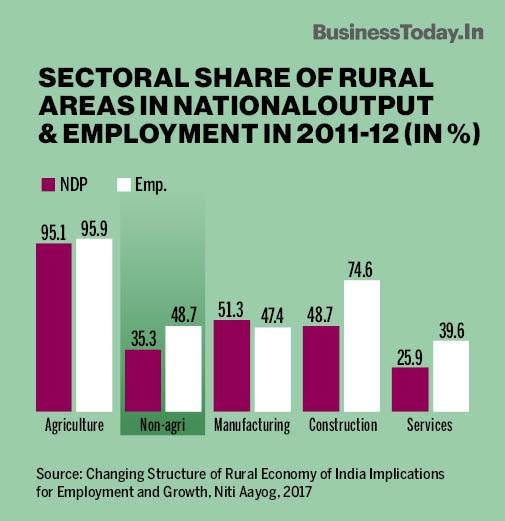

In 2011-12, the last year for which rural-urban contributions to output and employment are available, shows the rural economy's contribution to Net Domestic Product (NDP) was 46.9% and to employment 70.9%.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVI: Derailment of economy is not 'Act of God', it is 'Art of Misdirection'

Such rural-urban estimates are made only at the time of calculating GDP base-year. Rural area's shares in all six base-year estimates are mapped below to show how significant its role is.

In 2011-12, rural area's share to NDP and employment in different economic activities are also mapped below to provide a more granular picture. Non-agri activities shown in the graph include manufacturing, construction and services that follow.

What the above two graphs indicate is that any setback to the rural economy will cause a proportionate setback to national output and total employment, which would be quite substantial, and hence, India needs to pay more attention and estimate the true extent of rural distress due to the virus and economic disruptions.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXV: How a series of economic misadventures derailed India's growth story

No comments:

Post a Comment