Most governments across the world incentivise debts to drive business even when it leads to over-borrowing, economic instability, tax evasion and adversely impacts investment in public goods. In contrast, equity-driven business has none of these ill-effects, produces better economic outcomes too

Prasanna Mohanty | August 6, 2020 | Updated 18:42 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | August 6, 2020 | Updated 18:42 IST

That debt-driven growth model is deeply flawed and comes at a high cost to well-being of people (public goods) has been well recognised, especially after the US housing bubble fuelled by cheap debt burst that led to global recession in 2007-2008.

Yet, most governments around the world persist with the debt bias in two ways: (i) taxing the returns on equity (dividend) but exempting the returns on debt (interest) and (ii) keeping interest rates low to push debt.

Equity and debt (loan) being the two ways of mobilising capital, when equity is dis-incentivised, businesses opt for debt. There is considerable literature on the dangers of debt-driven business. It leads to over-borrowing, thereby increasing the probability of economic instability and crisis; reduces tax base; diverts public money from being invested in public goods (to raise standards of living); incentivises tax evasion and facilitates private gains with public money.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XIII: Why Indian corporates are debt-ridden

The debt bias has seeped so deep into business thinking that few realise it was a distortion introduced 102 years ago (in 1918) by the US Congress without explanation, which was then copied worldwide.

Let's begin the story backward from 2020.

Business case for debt-driven entrepreneurship

There is a good business case for debt-driven businesses.

Most tax laws allow tax-free debt. This is by allowing interest paid on debts (loans) deductible before profit is calculated, and treating interest paid as a cost to business.

Since businesses need capital, tax-free debt provides a cheaper source, lowers cost of production and improves competitiveness. On the other hand, dividend is not tax deductible (dividend is paid after tax is paid) because it is treated as income to business. Dividend is a division of income.

Most governments also sweeten debt by reducing interest rates.

Some governments, like the US, have kept interest rate near zero (0.25%) for years, even after the experience of 2000-01 dot-com bubble and 2007-08 housing bubble which, when burst, led to millions of job losses, wiped out pension savings of a few more millions and demise of big financial institutions, some of which were bailed out with public money.

Many countries, like India, give tax concessions, regulatory and administrative incentives (called "ease of doing business") to attract FDI. To encourage domestic businesses, India and the US have cut corporate tax and lowered interest rates to borrow more. India's banking regulator RBI cut repo rate from 6% in April 2018 to 3.5% in May 2020 and CRR to 3% in FY21.

Besides, India offers two additional advantages on borrowing.

First, debt default, even if wilful, is written off routinely as NPA without too many questions. The RBI protects defaulters by not naming them or revealing NPAs being write-offs since 2019 and erasing earlier data from its database. (For more read 'Rebooting Economy IX: Why is private sector dependent on public money in times of crisis? ').

Second, it diluted the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) of 2018, as former RBI Governor Urjit Patel revealed recently, opening the door for more loan abuse.

Further, India is contemplating one-time restructuring of stressed debts, the failure of which led to the IBC in the first place and/or extending moratorium on debt repayment beyond August 31, even after the RBI warned on July 24 that bad loans (GNPAs) of the Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs) could go up from 8.5% in FY20 to 14.7% in FY21.

India's largest public sector bank SBI issued a warning on August 3, stating that extension of moratorium would "do more harm than good". It gave two examples.

First, 70% of the total moratorium was availed by corporations rated 'A 'and above - those who can easily repay with "comfortable debt-equity ratio". Second, consumer loans declined by Rs 53,023 crore in the current fiscal but "consumer leverage in lieu of exposure to stock market" increased by Rs 469 crore that "could be a potential source of financial instability".

High cost of debt bias and debt-driven business

The negative effect of debt bias and debt-driven business model is well recognised.

Economist Joseph Stiglitz wrote in his paper of 2017, "Alternatives to Debt-driven Growth: Continuing in China's 40 year of Reform", that low-interest and tax-free debt regime lead to "market irrationalities that typically then appear in the pricing of risk: a search for yield drives down risk premia, and there is systematically excessive risk-taking".

A 2011 paper of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), "Tax Biases to Debt Finance: Assessing the Problem, Finding Solutions", asserted: "Legal, administrative, and economic considerations offer no compelling ground to systematically favor debt over equity finance."

It said the evidence showed debt bias "creates significant inequities, complexities, and economic distortions" by leading to inefficiently high debt-to-equity ratios in corporations; discrimination against innovative growth firms; impeding stronger economic growth; threat to public revenues due to tax evasion/avoidance and erosion in tax base. The cost to public welfare, though long recognised, could be far larger than previously thought because of the 2007-08 experience, it added.

It further said businesses respond to the incentives of debt bias more over time (i) leading to over-borrowing and too much risk taking by financial firms (ii) builds up excessive debts in banking system and (iii) increases chances of defaults and financial crisis and magnifies the depth of crisis, especially due to systemic effects of bank failure.

It highlighted three legal flaws causing debt bias: (a) debt holders have legal right to pre-fixed returns, irrespective of financial position but equity holders receive variable returns, based on performance of firms (b) debt holders have a prior claim to the firm's assets in case of insolvency, equity receive only "residual" claims after debt is repaid (c) suppliers of debt have no control rights over the firm, suppliers of equity do.

There are other downsides.

Tax-free debt comes at a very high cost to economies.

In 2015, The Economist pointed out that before the global recession hit in 2007, "tax foregone" on debt or "debt subsidy" cost the US 5% of its GDP or $725 billion and Europe 3% of its GDP or $510 billion.

In 2015, after the US had reduced interest rates "close to zero", tax subsidy still cost it more than 2% of GDP - an amount it spends on "all its policies to help the poor".

Another of its articles at the time called debt subsidy provided all over the world a "senseless subsidy" and "bad idea".

How much does it cost India? There is no data or known estimates.

There are other costs to debt bias too.

How debt bias incentivises tax evasion

The Tax Justice Network (TJN), an international network doing pioneering work to prevent tax evasion, explains mechanisms adopted by multinational companies (MNCs), private equity firms (PEs) and individuals exploit debt bias for tax evasion.

About MNCs, it says: An MNC first sets up a finance company in tax haven, which then lends money (internal debt) to other company/companies owned by the same MNC. Interest is paid to the tax haven-based company, thus moving money from higher tax countries to lower or no tax jurisdictions.

This practice is the order of the day. Global efforts to battle it since 2012 have failed to produce meaningful results.

The OECD-G20's BEPS initiative to check tax evasion started in 2012 and India's own General Anti Avoidance Rules (GAAR) was framed in 2012. Both are cosmetic exercises and have produced no results so far. India is yet to operationalise GAAR, extending the date of enforcement yearly. The next date is April 1, 2021. (For ore read 'Taxing the untaxed VIII: How India and multilateral bodies are fighting tax avoidance )

In case of external debt, TJN explained the mechanism: A company is first bought using borrowed money by a tax-haven based company. The debt is then transferred to the company bought, burdening it and lowering its value. After the debt is paid and normal level of profit returns (often accompanied with drastic cut in services, staff and wages) this company becomes more valuable, its shares are sold off to a tax haven holding company created for the purpose, which makes capital gains tax free. Or the company is sold off at a profit.

This is how private equity (PE) firms operate. When the plans fail, as it did in case of the UK's care homes, the UK government had to bail out the care facilities (for the old and infirm) with public money. (For more read 'Rebooting Economy XII: Is private sector inherently more efficient than public sector? ')

Advantages of incentivising equity and equity-driven business

The tax bias against dividend ensures that even if the dividend market is fully developed, businesses seek debt for capital. (In India, dividend was earlier taxable for both enterprises and equity holders (shareholders) but after the 2020 budget it is taxable only for equity holders, not businesses.)

There is no dispute that equity-driven business is a better business.

Stiglitz wrote in his 2017 paper: "Equity has a marked advantage over debt. When the fortunes of the company turn out to be less than expected, perhaps because of a cyclical downturn, perhaps because of unanticipated changes in market conditions, there doesn't have to be a costly debt restructuring."

He did caution though: "But with equity, the profits are supposed to be shared equitably among all the shareholders, and managers and the original owners often have the means of shifting profits towards themselves. But if enough firms do this (profit shifting to owners), there will be no confidence in the equity markets. Confidence in the equity market can only be assured through good norms."

Arguing the case for equity over debt, the IMF's 2011 paper said: "... introducing a deduction for corporate equity has better prospects... Apart from eliminating debt bias, such an allowance would bring other important economic benefits, such as increased investment, higher wages, and higher economic growth."

It pointed out that countries like Belgium, Brazil and Latvia successfully introduced variants of the allowance for corporate equity, suggesting that it was "not only conceptually desirable and practically feasible".

Has debt-driven business model delivered?

After 1970s' neoliberal (radical right) push by the World Bank and IMF, another dimension was added to tax laws: drastic cut in corporate tax. In India, for example, it is lower than individual income tax post-2019 tax cut.

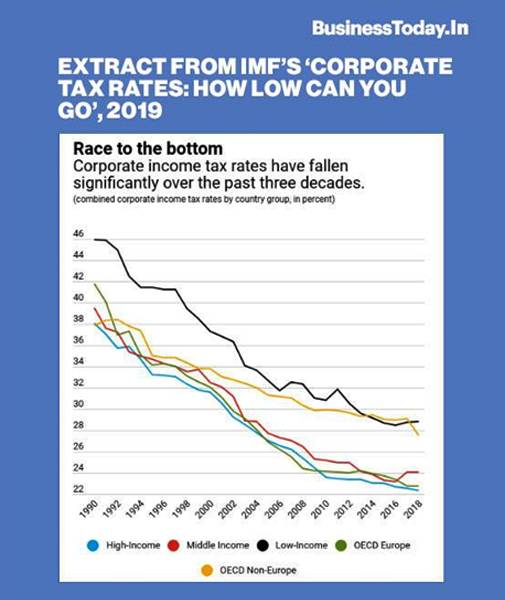

Such has been the drop in corporate tax that a 2019 internal paper of the IMF warned developing countries against its serious consequences: lowering government resources to boost growth and reduce poverty, undermining the fairness of tax system and encouraging tax avoidance and tax abuse.

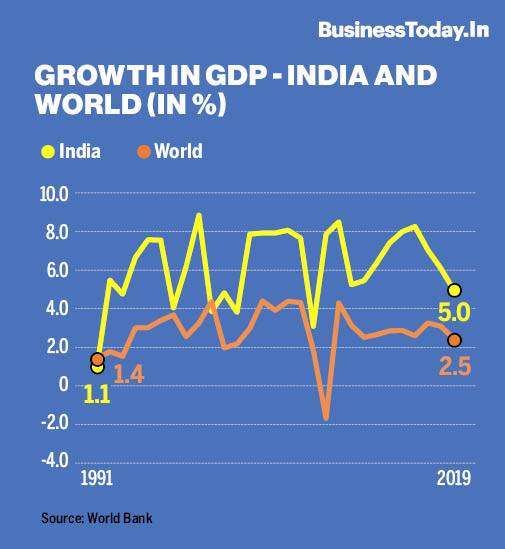

The following graph, taken from this IMF paper shows the drop in corporate tax and the next one shows the GDP growth globally and in India during the corresponding years.

Has worldwide corporate tax cut produced high growth it is premised on?

The US and India cut corporate tax in 2017 and 2019, respectively, by repeating the bizarre neoliberal economic concepts: tax cuts to rich benefits the non-rich.

In 2019, the US Congress discovered that the corporate tax cut led to stock markets, setting a new record in stock buybacks at $1 trillion. India never tried to find out, but its stock markets are booming even when the COVID-19 cases repeatedly crossed 50,000-mark per day, taking the total cases to over 19.6 lakh (as on August 6) and the economy continues to remain depressed.

On the other hand, economic history shows that during the golden age of capitalism between 1950s and 1970s, corporate tax rates were extremely high, unthinkable by today's standards. The average top corporate tax rate was 70-80% in the US and 99.25-80% in the UK. (For ore read 'Deconstructing Neoliberalism III: Why neoliberalism calls for a rethink ')

Alternatives to debt-driven business model

By now it is clear that equity-driven business is a better one.

While advocating it, Stiglitz suggested two measures in his 2017 paper: greater reliance on (a) taxation of public sector (to bring equity by taxing the rich) and (b) equity-driven model for private sector.

The IMF's 2011 paper called for complete dismantling of tax-free debt regime to ensure equal treatment of debt (loans) and equity. This would have several advantages: broaden tax base (debt is no more tax free), allow lowering of tax rates (attracting FDI); shift "tax burden away from economic rents towards marginal investment". However, when all countries pursue the same policy, the benefits will disappear.

It also forwarded an argument for going beyond neutrality to penalise debt financing for adverse spill-over effects (systemic failure and contagion effects). In this, an allowance on equity is meant to obtain neutrality first and then a higher tax debt to discourage sectors where externalities are most relevant: financial sector.

It concluded: "These two pillars (penalising debt and incentivising equity) together are also attractive from budgetary and political perspectives since they combine a lower tax burden for firms that invest in new assets with a higher tax burden for firms that feature excessive levels of debt. The budgetary cost of the reform can thus remain limited and the tax burden shifted from desirable to harmful behavior."

Now is the time to answer another important question: How did debt turn tax-free?

Why and how debt became completely tax free

Here is what happened 102 years ago, in 1918.

A Duke University professor Alvin C Warren, Jr narrated this story in his paper, "The Corporate Interest Deduction: A Policy Evaluation", published in the Yale Law Journal in 1974.

He wrote: "The unlimited deduction for corporate interest payments originated in 1918 as a temporary measure designed to equalise the effects of the World War I excess profits tax. Before 1918, only limited offsets against corporate income were granted for interest payments, apparently because Congress feared that corporations would try to avoid taxation by substituting bonds for stock."

He went on to add: "When the excess profits tax was repealed in 1921, the full interest deduction was retained as part of, the corporate income tax, without any explanation by Congress in the legislative history."

"Excess profits tax" was imposed after World War I to generate additional resources for reconstruction of war ravaged Europe that spread to other parts of the world. The logic being: some traders and businesses (like food and ammunitions) profiteered and recorded windfall gains due to war-time situation (scarcity, inflation, restrictions on movement of goods) without really bringing value additions and thus branded "unearned".

The concept originated in Denmark and Sweden in 1915 and by 2017 had spread to 13 countries "like the Spanish influenza" as another American economist Carl C. Plehn wrote in his 1920 paper "War Profits and Excess Profits Taxes".

When the US allowed "unlimited deduction" of interest on debts in 1918, it was justified on the ground that war time "excess profits" were earned on "invested capital", but "borrowed money" (debt) did not come in the definition of "invested capital". So, the US Congress reasoned that it was "only fair" that interest on corporate indebtedness be fully deductible.

Warren's paper tells that tax discrimination of debt and equity is an old concept, as old as the accounting concepts of what are cost and income to a business. Interest on debt has always been clubbed with wages, rent and supplies as a cost, while dividend has always been a "division of profit" or income, not an expense.

The logic endures and so does the distortion.

No comments:

Post a Comment