Profit-driven enterprises are ill-suited to protect the health and life of a vast majority of people, as the US and Indian governments experience, but do precious little, thereby failing in their primary duty

Prasanna Mohanty | July 27, 2020 | Updated 21:30 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | July 27, 2020 | Updated 21:30 IST

India's private healthcare accounts for 70% of national healthcare needs and yet when the pandemic hit, almost all of private healthcare facilities shut down

The COVID-19 should serve as a wake-up call for all those who advocate private sector's superiority over public sector.

The United States (US) is a good example to begin with.

COVID-19 exposes US's private sector-driven healthcare

Ever since the coronavirus pandemic hit, there has been a flood of reports, studies, and analysis saying why and how the US healthcare system largely driven by private providers (hospitals and health insurance) has failed spectacularly to protect the health and life of its citizens.

The best argument against its private healthcare system is the continued surge in the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths when other developed countries have contained it. The US has repeatedly breached the 70,000-mark in new cases per day in recent days, and India crossed 49,000 new cases on Monday (July 27).

Also Read: Rebooting Economy IX: Why is private sector dependent on public money in times of crisis?

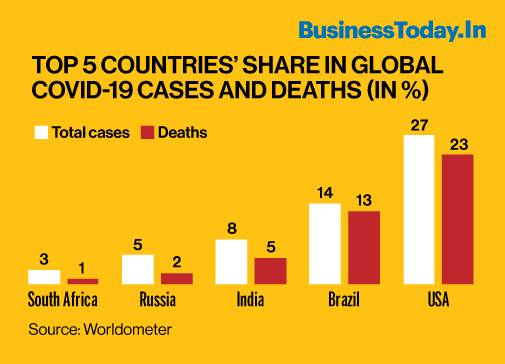

The US maintains its lead in both the number of cases and deaths month after month. As on July 23, the US accounted for 27% of total cases and 23% of total deaths. India is third in rank with a share of 8% and 5%, respectively. The total number of cases in both countries has crossed 4.3 million and 1.4 million as of date, respectively.

This surge is not entirely due to the inefficiencies of private healthcare for sure. The failure of political leadership is equally to blame but there is no disputing that a better healthcare system would have made a significant difference through access (inclusion) and affordability to quality healthcare.

The Commonwealth Fund's latest study published on January 30, 2020, says that the US spends the most on healthcare - 16.9% of its GDP or $3.5 trillion in 2018, which is nearly twice the OECD average - but is one of the worst when it comes to results.

It says, among the OECD peers, the US has the lowest life expectancy and highest suicide rates; it has among the highest number of hospitalisations from preventable causes and rate of avoidable deaths and its out-pocket spending second highest, next to Switzerland.

The US-based Brookings Institute's March 10, 2020 paper says the US healthcare is "largely consists of private providers and private insurance" and in 2018, the government insurance or direct provisioning (for poor and old) accounted only for 34% of citizens.

A joint study of Harvard, Cambridge, and London School of Economics, published in 2018, found 10% of the US citizens without any health insurance cover - the highest among high-income countries. It had the highest number of people, 55.3%, under private insurance.

The US is the only big developed country which doesn't have a universal healthcare system, its healthcare and insurance cost is prohibitively costly even for the young and since its private insurance is linked to employment, millions who lost their jobs to the lockdown are without protection.

Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz puts the blame on the US's higher cost with poorer outcomes to its profit-driven system in his 2019 book 'People, Power and Profits'.

India follows the US model of healthcare

The US experience should concern India, as it has been chasing the same model since 1991's liberalisation, cutting down public spending on health and promoting private care. India's public spending is one of the lowest in the world - a paltry 0.98% to 1.28% of its GDP during FY10-FY18 - lower than even the low-income countries (India is a low-medium country).

India's out-of-pocket expenditure is sky-high. At 62% in 2017 (the last year for which comparative data is available), it was 3.4 times the global average of 18% that year, driving 63 million Indians into poverty every year due to "catastrophic" health expenditure, according to official documents. (For more read 'Rebooting Economy VIII: COVID-19 pandemic could push millions of Indians into poverty and hunger ')

A comparative trend in out-of-pocket expenditure as percentage of total expenditure for India, China, US, and world average is mapped in the following graph.

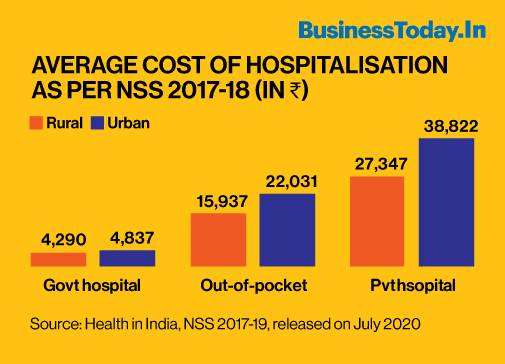

The following graph captures the latest official data of the National Sample Survey (NSS) of 2017-18, released in July 2020, showing how the average cost of hospitalisation in private sector is 6 to 8 times higher than government hospitals and out-of-pocket expenditure constitutes more than half of private hospitalisation cost.

India is perhaps the only country in the world where even public healthcare entails "catastrophic" out-of-pocket expenditure. The 2015 draft National Health Policy said "almost all hospitalisation even in public hospitals leads to catastrophic health expenditures" and that "there is no financial protection for the vast majority of healthcare needs.

Even the fully-paid government-run health insurance scheme Ayushman Bharat (PM-JAY) entails out-of-pocket expenditure. (For more read 'Coronavirus Lockdown VI: How India's insurance-led private healthcare cripples its ability to fight COVID-19')

The Ayushman Bharat scheme was launched in 2018 to provide free healthcare to bottom 40% of the population. In January 2020, the Indian Medical Association, the apex body of medical professionals in India, issued a public statement which said: "Ayushman Bharat, the flagship of the current government, is a non-starter and operates more in government hospitals where treatment is already free. 15% of the money paid to hospitals, including government hospitals. is siphoned off by insurance companies..."

Dominant private sector on the fringe during crisis

India's private healthcare accounts for 70% of national healthcare needs and yet when the pandemic hit, almost all of private healthcare facilities shut down. Most of them remain shut even now. Those which have joined the fight have been forced under the emergency powers of the National Disaster Management Act of 2005, which provides for "compensation" for such work.

States like Maharashtra and Bihar have to repeatedly threaten private healthcare to provide non-COVID-19 treatment and yet there is little progress, forcing medical experts and civil society to issue almost daily appeals. (For more read 'Coronavirus Lockdown XI: Why India's health policy needs a course correction ')

The national crisis hasn't stopped private healthcare from profiteering either. Earlier this month, Karnataka's health minister threatened a private hospital for giving an estimate of Rs 9 lakh to treat breathlessness. This is for illustration purpose, for such cases abound.

Concerned citizens have approached the Supreme Court (SC) but that hasn't helped so far. In April, it did direct private path labs to test COVID-19 cases for free but quickly retracted. On that occasion, solicitor general Tushar Mehta and former attorney general Mukul Rohtagi had assured the apex court that the government was doing all that was needed to care for the vulnerable.

On July 14, the top court heard another petition seeking a cap on COVID-19 treatment cost in private hospitals because of frequent complaints of "exorbitant" costs. The court is reported to have said that their exorbitant costs "must not dissuade patients" and asked petitioners and representatives of private hospital associations to meet health ministry officials to resolve the issue of hospitalisation cost."

Two facts are relevant here.

One, solicitor general Tushar Mehta told the court that the government had already put a cost fixation mechanism in place which varied from state to state. This is true.

For example, on June 19, following complaints of fleecing by private hospitals in Delhi, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) slashed charges by one-third. The new rates ranged from Rs 8,000 (isolation bed) to Rs 18,000 (ICUs with ventilator) per day. On June 6, Tamil Nadu had already capped per day general ward cost at Rs 7,500 and ICU cost at Rs 15,000 for private hospitals.

It is unlikely the Supreme Court was unaware of this.

It is also unlikely that the court didn't know about the NSS's 2017-18 consumption expenditure survey, which revealed that 'real' monthly household consumption (MPCE) had fallen for the first time in four decades from Rs 1,501 in 2011-12 to Rs 1,446 in 2017-18. The report wasn't officially released for its critical findings but it did hit the headlines across media through a 'leaked' report.

The question that arises here is: If the average monthly household expenditure (MPCE) - a proxy for monthly average income level of households in India since India does not measure household incomes - is Rs 1,446, how many Indians can afford a daily healthcare cost of Rs 7,500 to Rs 18,000 - 5 to 12 times their monthly income?

The amount of Rs 1,446 may be for 2017-18 but there is no credible evidence to say this has gone up in subsequent years. Secondly, loss of jobs and income has hit astronomical levels due to the prolonged lockdown, impoverishing millions of Indians. Thirdly, India's GDP growth has fallen from 8.1% in Q4 of FY18 to 3.2% in Q4 of FY20.

A global study suggests the lockdown could impoverish 352 million to 528 million Indians. The government is not even tracking job and income losses at this hour due to health and economic crises.

Should then "exorbitant cost" of private healthcare not provoke the Supreme Court to put breaks?

Pharmaceutical companies, patents and organised crime

There is another serious aspect to private sector in healthcare.

Private pharmaceutical companies are particularly notorious for profiteering from human misery. There is plenty of literature and historical evidence for this. Here are some lesser-known facts and information.

On May 27, Washington Post carried a news piece headlined "Taxpayers paid to develop remdesivir but will have no say when Gilead sets the price". Remdesivir is an antiviral drug which has emerged as a potential candidate for COVID-19 treatment and is being tested for efficacy. It has been found to reduce hospitalisation period by a few days. Gilead Sciences is the pharmaceutical company that makes it.

The report explained that several years ago when Remdesivir was being developed as an antiviral drug "three federal health agencies" provided "tens of millions of dollars of government research support" to it.

It further pointed out: "Despite the heavy subsidies, federal agencies have not asserted patent rights to Gilead's drug (Remdesivir), potentially a blockbuster therapy worth billions of dollars. That means Gilead will have few constraints other than political pressure when it sets a price in coming weeks. Critics are urging the Trump administration to take a more aggressive approach."

The report quoted Lloyd Doggett (D-Tex.), chairman of the House Ways and Means health subcommittee saying: "Without direct public investment and tax subsidies, this drug would apparently have remained in the scrapheap of unsuccessful drugs."

Gilead acknowledges it, but says "the original compound was discovered" by it and hence its proprietorial claim (to fix the price).

Here are a few other examples from Stiglitz's book, 'People, Power and Profits' for more light.

Taking about "stealth theft" by pharmaceutical companies in supplying drugs to the US government, Stiglitz writes: "The pharmaceutical companies put a little provision in the law providing the elderly with drugs under Medicare: the government, the largest buyer of drugs in the world, was not allowed to bargain on price. This and other provisions were put in at the behest of the drug companies to generate higher prices and profits."

He goes on to add: "It worked. Medicare drugs cost far more than those provided, say, by other government programs, like Medicaid for the poor or those for veterans. For the same brand-name drugs, Medicare pays 73 percent more. The result is that every year, taxpayers' fork over tens of billions of additional dollars to the drug companies."

Stiglitz narrates how big pharma companies use patent and other laws to keep cheap generic drugs out of market, often with the US government help, to make higher profits at the cost of consumers and government.

One method is to introduce a "time-release version" of an existing drug before its patent expires to extend the patent protection and prevent its generic versions to emerge. The "time-release version" (drug released in small amount over a time period) is not a new drug but by way of legal provisions called "data exclusivity" the relevant data on the original drug is restricted to prevent generic versions.

He cites some specific instances. For instance, Turing Pharmaceuticals increased the price of Daraprim, an out-of-patent drug, in 2015 from $13.5 a tablet to $750 a tablet. Another major company Valeant, the only FDI-approved manufacturer of the out-of-patent drug Syprine, a life-saving drug for a rare liver condition, "which sells for a dollar in some countries" so that a year's supply cost $300,000 by using its market power in 2015.

How allowing generic drugs helps can be revealing. Here is a case of India.

In 2012, Hyderabad-based Natco Pharma got "compulsory license" to make a generic version of anti-cancer drug Nexavar sold by Germany's manufacturer Bayer bringing down a month's cost of the drug from Rs 2,84,428 to Rs 8,800.

That could happen because (i) Bayer did not start producing the drug in India within three years of getting a licence as was required under the Indian Patents Act of 1970 but continued to import it and (ii) the WTO allows such a move on humanitarian grounds.

India's reverse journey: from self-sufficient to import-dependent

India's negligence of public sector pharmaceutical companies has turned it from self-sufficiency to important-dependent. India imports two-thirds of its active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) and formulations from China (the trade war has disrupted it now).

Two key public sector companies, Indian Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Ltd (IDPL) and Hindustan Antibiotics Ltd (HAL), have turned sick due to prolonged negligence. Last year the central government decided to close down IDPL and its subsidiary Rajasthan Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Ltd (RDPL) and sell off HAL and Bengal Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals Ltd (BCPL).

Such negligence by the government and profit-driven operation of private sector has led to the disappearance of cheap and antibiotic wonder drug penicillin from India.

HAL was set up in 1950s to produce penicillin commercially. When, in late 2019, the Indian government wanted to produce it again, the HAL expressed its inability. While penicillin is a key element of treatment in the UK's healthcare system, it can't be found in India. No private sector pharma company is interested in producing cheap drugs, their usefulness notwithstanding.

India largely depends on China for the supply of Penicillin G to use it as a raw material for manufacturing antibiotics. (For more read 'Coronavirus Lockdown VII: What India can learn from COVID-19 hit nations ').

No comments:

Post a Comment