Latest job loss survey and national accounts statistics point to the need for strengthening PDS supply and cash transfers to reach more people, assisting self-employed/micro-enterprises, additional allocation for MGNREGS and a job scheme for urban areas

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: June 3, 2020 | 16:33 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: June 3, 2020 | 16:33 IST

Of the 276.2 million people who have lost their jobs, 103.7 million reside in urban areas while 128.5 million dwell in rural areas

By now it is clear that no government agency is tracking the massive job loss that the COVID-19 pandemic-induced lockdown has caused. On June 1, a union minister admitted it in so many words. This is the first hurdle to designing the right response. However, many non-government agencies, including the Mumbai-based Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) and the Bangalore-based Azim Premji University, are tracking job loss (as well as the impact of relief measures) which can be used for redesigning the responses.

Magnitude of livelihood crisis: Job loss and reverse migration

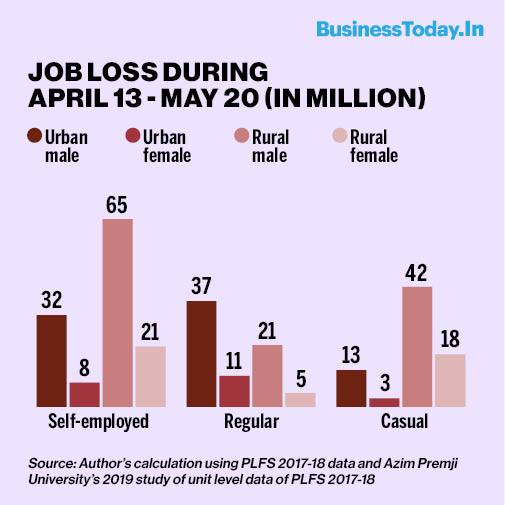

The Azim Premji University's survey provides a detailed account of job loss across all three categories of workers - self-employed, regular and casual - in urban and rural areas as well as for male and female workers.

Its findings, based on the survey carried out during April 13-May 20, 2020 across 12 states, show a high percentage of job loss across the spectrum - as reproduced below.

The percentage of job loss translates into a total loss of 276.2 million jobs.

This estimate is arrived at by taking into consideration two factors: (i) total workforce at 465.1 million for 2017-18, as estimated by Azim Premji University's 2019 study that analysed the unit level data provided by the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) of 2017-18 and (ii) using the same proportion of male and female workers, in urban and rural areas and across all three categories of workers as the PLFS of 2017-18 findings suggest.

The actual numbers could be different, but no official data is available beyond 2017-18.

Of the 276.2 million people who have lost their jobs, 103.7 million reside in urban areas while 128.5 million dwell in rural areas (mapped below).

The number of actual affected people would be more because a large number of migrants going home are taking their families along. Most of them are going to Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh, some of the most backward states with limited financial resources.

Additional stress for the slowing economy

Every reverse migration puts additional burden on the rural economy. Firstly, there would be no remittances from urban areas to support the rural economy. Some estimates suggest 80% plunge in domestic remittances by the first week of April. Secondly, there is a massive job loss in the rural areas also, reducing the pie further.

Urban areas are now without a significant chunk of workers. Even if they return and economic activities begin immediately, the fear of the virus, social distancing norms in factories, offices, and housing would prevent their re-hiring en masse. Re-hiring would be staggered.

But more importantly, there may not be enough room or economic activities for re-hiring them for many months. Here is why.

Going back to pre-pandemic GDP growth rate may take long

The latest national accounts statistics released on May 29, 2020, shows that the GDP growth in the last quarter of FY20 (January to March) slumped to 3.1% - the lowest in 44 quarters (11 years since 3.09% in FY09).

The real state of the economy in the first quarter of FY21 would be far worse (would be known in August).

The quarterly data released for FY19 and FY20 shows agriculture recording far better growth, touching 5.9% in Q4 of FY20, which is higher than the rest but here is a catch. Its share in total GVA for Q4 of FY20 is 15.6%, while it supports 43.21% of the total workforce of India, as per the ILO data for 2019 (that would closely match with FY20).

Evidently, the income generated from agriculture is too low to adequately support the additional influx even with higher growth.

The growth in manufacturing has been negative for three quarters and in construction for two. The numbers could be far worse in the current fiscal, seriously limiting their capacity to absorb workers. In Q4 of FY20, the manufacturing's share of GVA is 17.8% while its share of workers is 11.4%; the share of construction in GVA is 7.9% while its share of workers is 12.3% (using ILO estimates for 2019 for workers' share).

Also read: Coronavirus Lockdown XVI: Why India should be wary of excessive push for liquidity or credit

The current fiscal (FY21) is likely to witness negative GDP growth, as the RBI governor said on May 22. Economist Pronab Sen warns that if the stimulus is not sufficient (fiscal spending of 10% of the GDP), the negative growth may spread to the next fiscal (FY22), dragging India into a depression.

All this would mean the level of economic activity may not be good enough for a year or more to accommodate all those who have lost jobs and livelihoods (the self-employed, for example). The overall growth rate has to reach at least the pre-COVID-19 level for that.

That is why India needs to recalibrate its strategies towards workers and their families.

Recalibrating response to human suffering

The Azim Premji University's survey also maps how the lockdown and subsequent job and livelihood losses have impacted households.

Also Read: Coronavirus Lockdown XV: Not just stimulus 2.0, getting fiscal mathematics right is critical too

It says 83% of urban and 73% of rural households are consuming less food than before, which is expected in such circumstances. It also says that 64% urban and 35% of rural households don't have enough money to buy a week's worth of essentials. This should be a cause of worry.

As for the relief measures, 84.8% of the rural and 65% of urban households received ration; 41% of vulnerable households in rural areas and 23.8% in urban areas received Jan Dhan Account transfers; 26% of rural households received the PM-KISAN transfers and 58% and 36% of households in rural and urban areas, respectively, received at least one cash transfer.

The task is, therefore, to reach out to the left out vulnerable households with more food supply through the public distribution system (PDS) and more cash transfers.

Idle construction workers' fund, inadequate MGNREGS allocation

Though the March relief package allowed Rs 52,000 crore lying idle in the construction workers' welfare fund to be transferred to them, there is no indication of any progress.

This is primarily because the fund has been largely sitting idle for decades.

This fund resulted from two central laws of 1966 - The Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act of 1996 and The Building and Other Construction Workers' Welfare Cess Act of 1996.

In 2018, the Supreme Court took note of official apathy in not passing on the benefits and entitlements to construction workers, pointing out that millions of construction workers had not been identified and their whereabouts not known. It also pointed to a Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report which had red-flagged the same.

Since then, two new labour codes have been introduced in the Parliament - Occupational Safety, Health and Working Condition Code (OSFWC) of 2019 and Code on Social Security (CSS) of 2019 - proposing to repeal these laws. Thus, the utilisation of the fund is suspect.

Another key tool for relief is the rural job guarantee scheme, MGNREGS. An additional allocation of Rs 40,000 crore has been made in the Rs 21 lakh crore relief package, taking the total allocation for FY21 to Rs 100,568 crore. However, Rs 11,000 crore of this is pending dues for FY20, reducing the availability to Rs 89,568 crore.

Prof. Reetika Khera of the IIM-Ahmedabad, who has been studying the MGNREGS works, estimates that Rs 2.8 lakh crore would be needed to provide 100 days of work to the existing 140 million job card holding households- much more than the current allocation.

Accommodating additional demand for work from the migrants and those who lost their jobs in rural areas would require additional allocation.

Job scheme in urban areas and assistance for self-employed

For years economists have been seeking a MGNREGS-like job guarantee scheme for urban areas because of high unemployment. The current situation highlights the need for this even more.

This will not only benefit those who have lost jobs and stayed back, but also those who return to seek jobs but would have to wait for many months before the economic activities pick up to re-hire them.

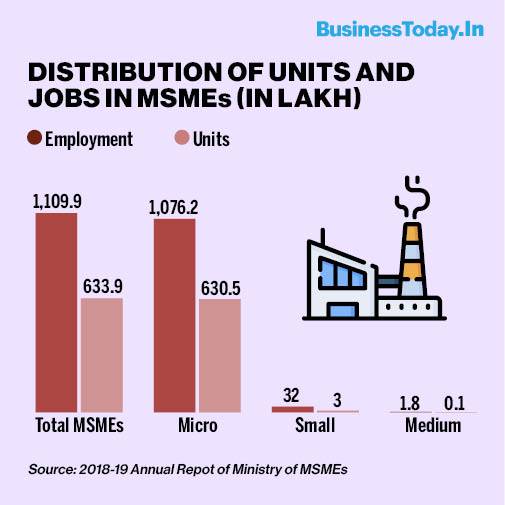

The self-employed workers constitute 52.2% of India's total workforce and have been badly hit due to the lockdown too. They are the ones who run micro-enterprises, that constitute 99.46% of units and provide 97% of employment in the MSME sector - according to the ministry of MSME's 2018-19 annual report.

These micro enterprises are more or less evenly spread in rural and urban areas and on an average, employ less than 2 workers, meaning that many are a one-man show.

All credit facilities for the MSME sector announced so far (Rs 3 lakh crore emergency working capital or Rs 20,000 crore subordinate debt) are more likely to bypass the micro-units. Even the Fund of Funds, set up for equity infusion of Rs 50,000 crore (but only with a corpus of Rs 10,000 crore), is meant for expansion in size and capacity of MSMEs and encouraging their listing in stock markets.

This too is unlikely to offer much help to micro-enterprises under a threat to survive.

It is for all these reasons that India's response needs to be redesigned so that a large part of its population rides over the multiple crises facing them.

No comments:

Post a Comment