RBI data shows excess liquidity is lying idle, parked in its own reverse repo account, and burdening it with higher interest payouts. This could be tapped and channelised for additional fiscal spending to stimulate growth through government bonds

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: June 3, 2020 | 15:11 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: June 3, 2020 | 15:11 IST

The RBI has cut repo rate from 5.15% to 4% and the reverse repo rate from 4.9% on 3.35% during January to May 2020

The last time the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) spelt out its monetary policy on May 22, it reduced the repo rate (at which commercial banks borrow money from it) and the reverse repo rate (it pays to commercial banks), reiterating its "pro-active" liquidity management policy to "augment system-level liquidity" even while admitting that "credit growth remains muted" and that "high-frequency indicators point to a collapse in demand beginning March 2020 across both urban and rural segments".

The RBI has been on a liquidity infusion spree for quite some time. It has brought the cash reserve ratio (CRR), freeing up more money in commercial banks for lending, repeatedly cutting the repo rate and using instruments like Long-Term Repo Operations, Targeted Long Term Repo Operations, Targeted Long Term Repo Operations 2.0, etc. to generate more liquidity.

But what is happening to the excess liquidity being generated?

Where is this liquidity infusion going?

Here is what the RBI's high-frequency data shows.

The following graph uses the RBI's money market operation data (from January 1 to May 28, 2020) to map deposits in its reverse repo account - where commercial banks park their money for a day or more when they don't or can't lend.

It shows a dramatic rise in deposits from a few thousand crore of rupee in January and February to more than Rs 8 lakh crore in May.

The repo rate has been cut from 5.15% to 4% and the reverse repo rate from 4.9% on 3.35% during this period (January to May 2020). In March it had cut the CRR to 3% for a period of one year, from 4%.

Cuts in the reverse repo rate is to discourage banks from parking their money with the RBI and lend it, instead, to productive or real sectors where they would earn higher interest, but it has made little difference.

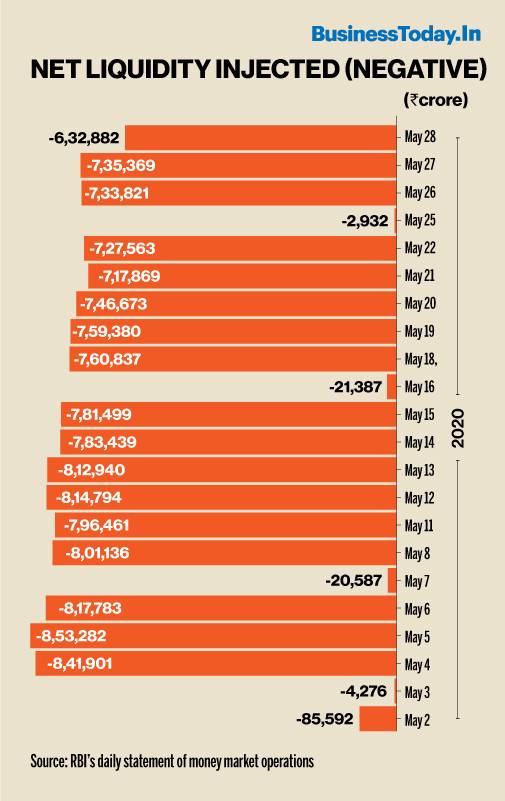

Net liquidity injection is negative

The following graph uses the RBI's daily bulletin on money market operations for the month of May 2020. These statements have a specific row marked "Net liquidity injected from today's operations".

As the graph shows, the net liquidity injection into the economy is negative, and hugely so. This corresponds to the reverse repo deposits (fixed). The net liquidity injection crossed the (-) Rs 8 lakh crore mark several times in the month.

Poor demand for credit in the economy

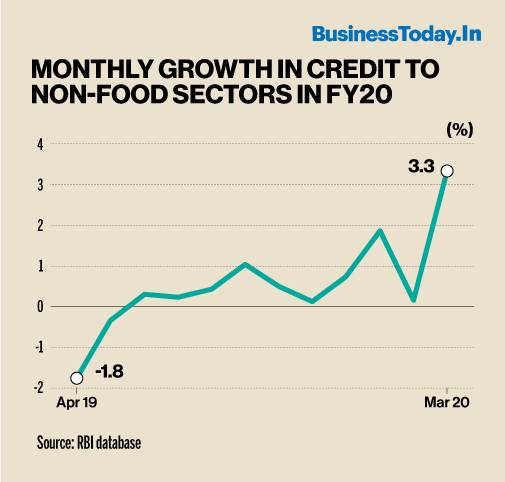

There is another indicator of the movement of liquidity: growth in credit outflow.

The next graph maps growth in credit outflow to the non-food sectors (all sectors except for food grain procurement), like agriculture, small, medium and large industries, services and personal loans for housing, education, consumer durables, vehicles etc.

The annual growth rate of credit to the non-food sector shows a significant fall to 6.7% in FY20 - which is a 58-year low. The decline has been steady for several years.

The monthly credit growth for FY20 has remained less than 4%.

A few things are clear from the above four graphs.

One, with greater liquidity, more and more money is sitting idle in the RBI's reverse repo account where it is not needed.

Two, the reverse repo rate may have been lowered, but the quantum jump in deposits is creating a higher interest liability for the RBI.

Also read: Coronavirus Lockdown XVI: Why India should be wary of excessive push for liquidity or credit

Three, higher liquidity is not going where it is needed, that is the productive or real sectors of the economy which produce goods and services, because banks are averse to lending due to stressed assets and lack of demand.

Is India in a liquidity trap?

The RBI's data demonstrates how its best efforts to generate more liquidity in the system have not translated into higher credit outflow or investment in the past few years.

That is because there is more to investment than just interest rates. While the industry already has excess capacity (both production and capacity utilisation had been reduced even before the pandemic hit), the lowering of interest or higher infusion of liquidity is of no use until demand revives and the economy starts growing again.

The Credit Suisse's May 26 report, 'India Financial Sector', says despite growing liquidity, banks have turned even more risk-averse and in the past 12 months, more than 90% of their incremental lending has been to >A-rated corporates. (Many of the banks are in the process of mergers announced earlier.) The report further says, NBFCs have held back after the collapse of the IL&FS in 2018; small private banks are pulling back and ECBs and bond markets are shut, leading to a major constraint on the financial system's lending.

On May 22, the RBI governor declared that the GDP growth in FY21 is likely to be negative. This would mean the economy would not be restored to its pre-pandemic growth level in FY21 and hence, the chances of growth in credit or investment picking up are very low for a year or more.

Prof Arun Kumar of Delhi's Institute of Social Sciences says, "We are in a liquidity trap, which means cutting interest rate will not lead to increase in investment".

India needs to rethink how to stimulate growth beyond just liquidity infusions.

What options India has to stimulate growth?

It is important to repeat that the lockdown has caused a massive loss of jobs and other livelihood options for people causing a demand depression. Leading economists have been arguing for quite some time that India needs to do primarily two things: (i) provide cash support to those who have lost jobs and other livelihood options and (ii) spend more keeping fiscal deficit concerns aside for the moment. Both would help in generating demand.

In May the central government increased gross market borrowing by Rs 4.2 lakh crore for FY21, taking the total to Rs 12 lakh crore, but this is aimed at filling the fall in revenue, rather than extra fiscal spending, and would raise the fiscal deficit from 3.5% to 5.5%. The fiscal spending component in the Rs 21 lakh crore package is only about 1% of the GDP. Additionally, the states have been allowed to borrow more - from 3% of GSDP to 5%.

Also Read: Coronavirus Lockdown XV: Not just stimulus 2.0, getting fiscal mathematics right is critical too

Will this be enough?

Business Today spoke with two economists with decades of experience in running India's economic affairs - Dr. C Rangarajan and Pronab Sen. Both think the current level of additional fiscal spending is not enough given the dire strait of the economy. They think spending 5% of the GDP (Rs 10 lakh crore) would be more appropriate with one difference. Rangarajan favours a staggered approach while Sen is for immediate action.

Rangarajan points to fiscal constraints in mobilising additional resources. He says the fiscal deficit is already touching 12% or more (centre and states taken together) while household savings (financial savings available for investment) are low (dipped to 6.5% of the GDP in FY19) and therefore, the RBI would have to monetise the current level of deficit. His suggestion: the government should spend all that is available to it now and think of additional spending later when growth picks up.

Sen warns that without additional fiscal spending now would mean the GDP growth would be negative in this fiscal (FY21) as well as in the next (FY22), dragging India into a depression.

He says the negative growth of this fiscal year would have a multiplier effect and exports are likely to be hit hard as the global economy slips into a recession, jeopardising growth in FY22.

But where would the money for additional spending come from?

Here, Sen says, the excess liquidity generated by the RBI would help.

The government could issue bonds to tap this liquidity and finance its spending.

Should the yield on bonds (currently around 6%) go beyond the comfort zone (7.5%, in his reckoning), the government could monetise the rest by going to the RBI.

Seen from this perspective, the excess liquidity sitting idle now could be put to productive use and stimulate growth.

No comments:

Post a Comment