While some developed economies have adopted anti-tax avoidance GAAR and digital tax on sales of multinationals, India has been deferring operationalisation of GAAR since 2012 and is also handicapped by lack of adequate studies and data

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: March 13, 2020 | 14:46 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: March 13, 2020 | 14:46 IST

Repeated postponement of the GAAR is not the only stumbling block. Unreliable and inadequate data is also a major constraint

In December 2019, the UK-based transparency campaign group Fair Tax Mark caused a global ripple by alleging that the big six US tech firms - Amazon, Facebook, Google, Netflix, Apple and Microsoft had avoided paying $100 billion in tax (or Rs 730,000 crore at exchange rate of Rs 73) over the past decade (2010 to 2019).

This amount is the gap between their declared tax liability (current tax provisions) and what they actually paid in tax.

What is worse, the tax avoidance "continued" post-2017 and the implementation of the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (which reduced corporate tax rate), "which indicates that historic aggressive tax avoidance is not only unresolved but still growing", said their investigating report, The Silicon Six and their $100 billion Global Tax Gap.

The gap between the headline tax rates and actual tax paid, better understood as effective tax rate was even higher during the period-$155.3 billion (Rs 11,33,690 crore at exchange rate of Rs 73).

Global tax avoidance by multinationals: $240 billion a year

But they are not the only ones.

The Financial Times, one of the world's leading news organisations carried out its own investigation in 2018 in which it examined 25 years of financial statements of the world's 10 biggest public companies by market capitalisation in nine sectors.

It also found that "the gap between companies' reporting of what they expect to pay in tax, and the actual payments as revealed by cash transfers has also grown because of anomalies in the tax system that encourages some US companies to park cash or profits overseas..."

While these two studies (Fair Tax Mark and Financial Times) were limited in their coverage of multinationals, there is an overall estimate of how much overall tax multinationals avoid.

This comes from the OECD-G20 initiative, Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS), meant to fight such tax avoidance: $240 billion every year (or Rs 17.4 lakh crore a year at exchange rate of Rs 73) - as reproduced below.

Over 135 countries, including India, are collaborating to put an end to tax avoidance strategies that exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules. They have drawn up a 15-point action plan which is in various stages of being implemented.

Relevance for India: Most tax avoidance happens on foreign soils

The Fair Tax Mark's investigation is relevant for India because it found that most of the tax avoidance took place outside the US, as have other such studies too.

The Silicon Six's operations outside the US accounted for 52% of their booked revenue and 64% of their booked profits. But the tax liability (current tax charges) from these operations was just 8.4% of the identified foreign profits, a mere third of their consolidated (total) tax charge of 25.3%.

The gap of $100 billion in the declared tax liability (current tax positions) and actual tax payment also point to a disturbing phenomenon: For a decade, these multinationals are making different disclosures to their shareholders and tax authorities.

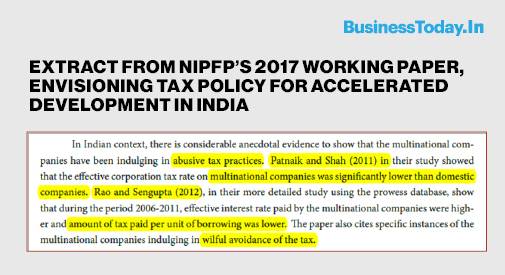

As for India, there is no recent study to rely on. A 2017 working paper of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), a finance ministry think tank, pointed to some such studies in the past and relied on anecdotal evidence to flag concerns about tax avoidance by multinationals.

The relevant paragraph is reproduced below.

How do they do it: Shifting revenue and profits to tax havens through subsidiaries

The Fair Tax Mark's investigation revealed a perceptible pattern of behaviour, shifting revenue and profits to tax havens, especially Bermuda, Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. While Bermuda is a no-tax jurisdiction, others are low-tax jurisdictions.

These tax havens figure prominently in India's FDI inflows and outflows too.

The businesses use various loopholes in different tax havens to shift profits between subsidiaries and lower tax burdens or avoid it, which go by colourful names such as 'Double Irish', 'Single Malt' and 'Dutch Sandwich'. There can be a combination of low-tax jurisdiction with a no-tax jurisdiction as the final destination.

Another study also came to a similar conclusion about the involvement of tax havens while investigating "phantom investments" by multinationals, investments that pass through empty corporate shells.

The IMF-University of Copenhagen published their report, The Rise of Phantom Investments, in September 2019. It said these empty corporate shells "undermine tax collection in advanced, emerging market and developing economies". It found 85% of all phantom investments being hosted by well-known tax havens of Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Hong Kong SAR, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Singapore, the Cayman Islands, Switzerland, Ireland and Mauritius.

Phantom investment was estimated at about $15 trillion of the total of $40 trillion of FDI being channelled around the world or 37.5% of the total FDI, up from about 30% a decade back.

Worryingly, it said most economies were now investing heavily in empty corporate shells abroad and received substantial investments from such entities which could indicate that domestically controlled multinationals engage in tax avoidance.

What is tax avoidance and why is it being frowned upon

Tax avoidance is not an illegal activity; it is a legal exploitation of existing tax laws to one's advantage. It has now lost acceptability globally after the 2007-08 global financial crisis and substantial lowering of corporate tax, from a global average of 40% in 1990 to about 25% in 2017.

Why is it then frowned upon?

The ORCD-G20's Action Plan on BEPS lists three reasons.

One, governments are harmed as they have to cope with less revenue, which leads to critical under-funding of public investments, undermines the integrity of tax system as low corporate tax is deemed unfair, and a higher cost of compliance.

Two, individual taxpayers are harmed as they bear a greater tax burden when some businesses are allowed to reduce the tax burden by shifting their income away from jurisdictions where income-producing activities are conducted.

Three, domestic businesses are harmed for not being able to compete by shifting their profits across borders to avoid or reduce tax.

In India, the Parthasarathi Shome Committee which examined the General Anti Avoidance Rules (GAAR) of 2012 in the Income Tax Act of 1961, brought in to check such tax avoidance commented: "On considerations of economic efficiency, fiscal justice and revenue productivity, a taxpayer should not be allowed to use legal structures or transactions exclusively to avoid tax."

GAAR: India defers the deadline to FY21

The GAAR of 2012 was introduced in India to guard against schemes designed for tax avoidance, following the hugely controversial tax dispute over telecom major Vodafone buying Hutchison Essar's India operations in a tax haven, the Cayman Islands, in 2007.

The GAAR provides that certain transactions would be "impermissible avoidance arrangement" (IAA) if (a) the main purpose is to obtain tax benefit and (b) it has one of the following characteristics: (i) it creates rights and obligations, which are not normally created between parties dealing at arm's length (ii) it results in misuse or abuse of the provisions of the tax law (iii) it lacks commercial substance and (iii) it is carried out by means or in a manner which is normally not employed for an authentic (bona fide) purpose.

The Parthasarathi Committee was set up to review it before being implemented. It recommended that the implementation should be deferred until FY17 for administrative reasons (lack of preparations, training and clarity on some concepts).

Since then the deadline is being extended. Last heard, it was deferred till March 31, 2020.

In the meanwhile, several advanced economies have implemented the GAAR, prominent among them are- the US, the UK, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Canada, New Zealand, China, Poland and Australia.

India lacks reliable data on the financials of multinationals

Repeated postponement of the GAAR is not the only stumbling block. Unreliable and inadequate data is also a major constraint.

While the Income Tax Department (ITD) does not provide relevant financial details, the RBI does for the FDI companies/enterprises, defined as entities in which a direct investor, who is a resident of another country, owns 10% or more of equity or voting power every year. This data is very problematic.

For one, each RBI report is based on surveys and provides financial data (sales, profit, tax, royalty etc.) for three fiscal years. This means, some years have multiple data on every entry as shown for 'current tax' in the graph below.

Secondly, the sample size varies each time, varying from 914 in FY13 survey to 9,428 in FY17 survey and 7,314 in FY18 survey. Besides, the coverage of the FDI companies varies in every survey too.

The lack of comparability of data makes any meaningful interpretation or understanding difficult.

What is the way out: Digital sales tax, unitary taxation

Apart from the GAAR, some of the developed economies have moved to adopt digital sales tax to counter profit-shifting.

Some countries like Austria, Czech Republic, France, India, Italy, New Zealand, Spain and the UK are considering or have progressed in introducing such a tax. These range from 2% (the UK) to 7% (Czech Republic) of sales. The focus is on corporate sales, not corporate profits in order to circumvent bilateral nation-to-nation tax treaties that may exist.

The OECD-G20 has initiated a 15-point action plan (BEPS). This is a multinational effort to ensure that profitable multinationals pay tax wherever they have significant consumer-facing activities and generate their profits and pay a minimum rate of tax even when they are operating in low-tax jurisdictions.

International tax experts, however, have been calling for changing the existing system. Instead of treating individual subsidiaries in different countries as separate taxable entities, as it is now, to a new taxation system which treats a multinational group as a single taxable unit.

No comments:

Post a Comment