Available information on the influx of "illegal migrants" doesn't warrant a nation-wide NPR-NRIC. The CAA 2019 was necessitated by the introduction of "illegal migrant" in Citizenship Act of 1955 during the Vajpayee regime in 2003 but it introduced another problem - religion-based citizenship - which has sparked a nation-wide strife

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: January 14, 2020 | 14:21 IST

Prasanna Mohanty Last Updated: January 14, 2020 | 14:21 IST

Often high influx of illegal migrants from Bangladesh is put forward to justify the threesome: CAA-NPR-NRIC

The fear of illegal migrants, especially from Bangladesh, has been raked up for taking a series of measures since 2003: Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2003 (CAA 2003) which brought in "illegal migrant" and National Register of Indian Citizens (NRIC) into the Citizenship Act of 1955; 2003 Rules under this amendment that brought in the National Population Register (NPR) and "doubtful citizenship" and Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2019 (CAA 2019) which introduced religion-based citizenship but excluding Muslims.

And now a gazette notification and separate allocation of funds for the NPR - a precursor to the NRIC - has been set in motion.

Is there really a need for all these measures which have sparked a country-wide protest, disrupting economic activities, civic peace and communal harmony? That the NPR-2020 manual circulated for enumerators and supervisors' calls for birth certificates of parents, it leaves none in doubt that the real purpose is preparing the NRIC.

This is likely to adversely affect all but most certainly the landless, illiterate and others who may find it difficult to produce the necessary documents, not to talk of high social, human and economic costs involved in such an exercise.

Here is a reality check.

Is migration to India a big problem?

Often high influx of illegal migrants from Bangladesh is put forward to justify the threesome: CAA-NPR-NRIC. Does the relevant data support such an assertion?

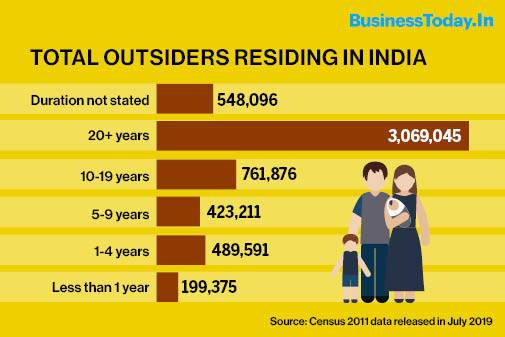

The Census 2011 data on outsiders residing in India, which was released only in July 2019, shows there has actually been a rapid fall in their influx in recent decades.

It shows those from Bangladesh numbered just 21,961 in 2011 - those who declared to be staying for less than a year in India. The steady decline is captured in the graph below.

The corresponding numbers from Afghanistan and Pakistan - the other two countries the migrants from which would benefit from the CAA 2019 - were 355 and 6,405, respectively, in 2011.

When it comes to the total number of outsiders residing in India, the trend is similar, as shown in the following graph.

Spike in voters not exclusive to Assam and West Bengal

India Today's Data Intelligence Unit (DIU) studied state-wise voters' lists, from 1971 to 2019 generation elections, to check if a large number of outsiders had indeed availed the voting rights, especially in Assam and West Bengal - another claim made to justify the CAA-NPR-NRC combine.

The findings were stunning:

(a) The average growth of voters during 1971-2019 in West Bengal was 10.4% and Assam 10.6% - against the national average of 11.1%. The spike was higher in Delhi (19.3%), Gujarat (12%) and Maharashtra (11.7%), indicating a high inter-state movement of people.

(b) Even during the period of 1971-1985, when influx was higher, the spike in Assam (61%), Tripura (71%) and West Bengal (49%) were higher than the national average (46%) but so was the case with Nagaland (115%), Delhi (73%), Gujarat (63%) and Haryana (62%).

More refugees from China (Tibetan) and Myanmar

DIU also analysed the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNHCR) data and found that most of the refugees residing in India on June 30, 2018 - numbering a total of 108,008 - are from China (Tibetans), followed by Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Afghanistan. More recently, in 2016, 2017 and 2018, most of the refugees are from Myanmar and Afghanistan. Both are captured in the graphs below.

The CAA 2019 stipulates only those from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan belonging to the Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian community will benefit, not others.

Is illegal immigration high?

The Government of India (GOI) has no clue.

On January 8, 2019, the then Minister of State for Home Kiran Rijiju gave a written answer to the Lok Sabha - reproduced below - saying that there was no "authentic survey" or "accurate data" on this, and for obvious reasons.

However, more than 30,000 people were staying on Long Term Visa (LTVs) who would benefit from the CAA 2019, he declared.

A Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) which went into the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill of 2016 (that was passed in 2019) and submitted its report in January 2019 put the beneficiaries at 31,313 who had already been given LTVs - as captured below. The government had said that in future inquiries would be made when fresh claims were made for citizenship.

Does India then need NPR-NRIC?

Prof Debarshi Das of IIT Guwahati, who has been actively engaged with Assam's NRC and illegal migrants says: "My sense is that there is no need for a country-wide NPR-NRIC for three reasons: (a) Assam experience shows it is very difficult for poor, illiterate, inter-state migrants to produce documents that are demanded for providing citizenship; (b) if we want to get rid of illegal migrants we should use police and intelligence agencies to identify them and tighten border security and (c) where is the data on illegal migrants that might warrant a country-wide NRIC?"

PC Mohanan, former chairman of the National Statistical Commission (NSC) says: "A sub-continent got divided artificially into three with no natural boundaries. Given the social, political and economic background, people were allowed to move in. They got integrated, have common physical features and language. There is no way a surveyor can identify them. Besides, in India, anyone can produce any kind of documents.

"Illegality of migration is our own construct. With my field experience, the NPR, and later the NRIC, will always be inconclusive. The NPR they talk of is found only in small countries with perfect civil registration."

Prof Faizan Mustafa, Vice-Chancellor of Hyderabad's NALSAR University of Law, says: "The migration from Bangladesh into India has come down as the Census data shows. With the Bangladesh economy doing better than us, there is hardly any economic incentive to infiltrate into India. The Right-wing created a false narrative about the exaggerated numbers of illegal immigrants and our apex court got carried away by those numbers leading to its erroneous judgment and subsequent insistence on Assam NRC."

Political scientist Prof Niraja Gopal Jayal writes that she is not aware of any example in the world in which the entire population has been asked to prove its citizenship. She gives the example of the UK which, in 2006, legislated national identity cards to be linked to a National Identity Register but realised its pitfalls, repealed it in 2011 and destroyed all data within a month.

Is there a need for CAA 2019?

PDT Achary, former Secretary-General of the Lok Sabha (2005-10) explains the need for the CAA 2019: "The CAA 2019 became necessary because the people who can be naturalised or registered as citizens should not be illegal migrants - as per the 2003 amendment in the Citizenship Act of 1955.

"But the CAA 2019 should have avoided classification of illegal migrants on the basis of their religious identities. That would have prevented this country-wide agitation and violence."

Thus, one problem was introduced in 2003 by the earlier NDA regime led by Atal Behari Vajpayee by introducing "illegal migrant" - defined as a foreigner who entered India (a) without valid documents and (b) with valid document but overstayed the permitted period.

The CAA 2019 introduced another problem by making religion the basis of granting citizenship to those illegal migrants but keeping the Muslims out of it, sparking a country-wide strife.

No need for NPR post-Aadhaar

Lastly, a new twist has been added by the Union Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad, who said recently, "There is a need for NPR because Census details cannot be made public to any authority, but NPR is required to frame policies for the delivery of welfare schemes."

The argument does not hold since the Aadhaar card is specifically designed for delivery of welfare schemes and have so far been issued to 125.1 crore people in India.

The title of the law under which these cards are issued - The Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act of 2016 - reflects nothing else. So, why this fig leaf of justification for NPR-NRIC when none exists?

No comments:

Post a Comment