There is an urgent need for a national employment policy which would take a comprehensive view of the challenges and set out to overcome them.

- Prasanna Mohanty

- New Delhi

- May 22, 2019

- UPDATED: June 5, 2019 17:37 IST

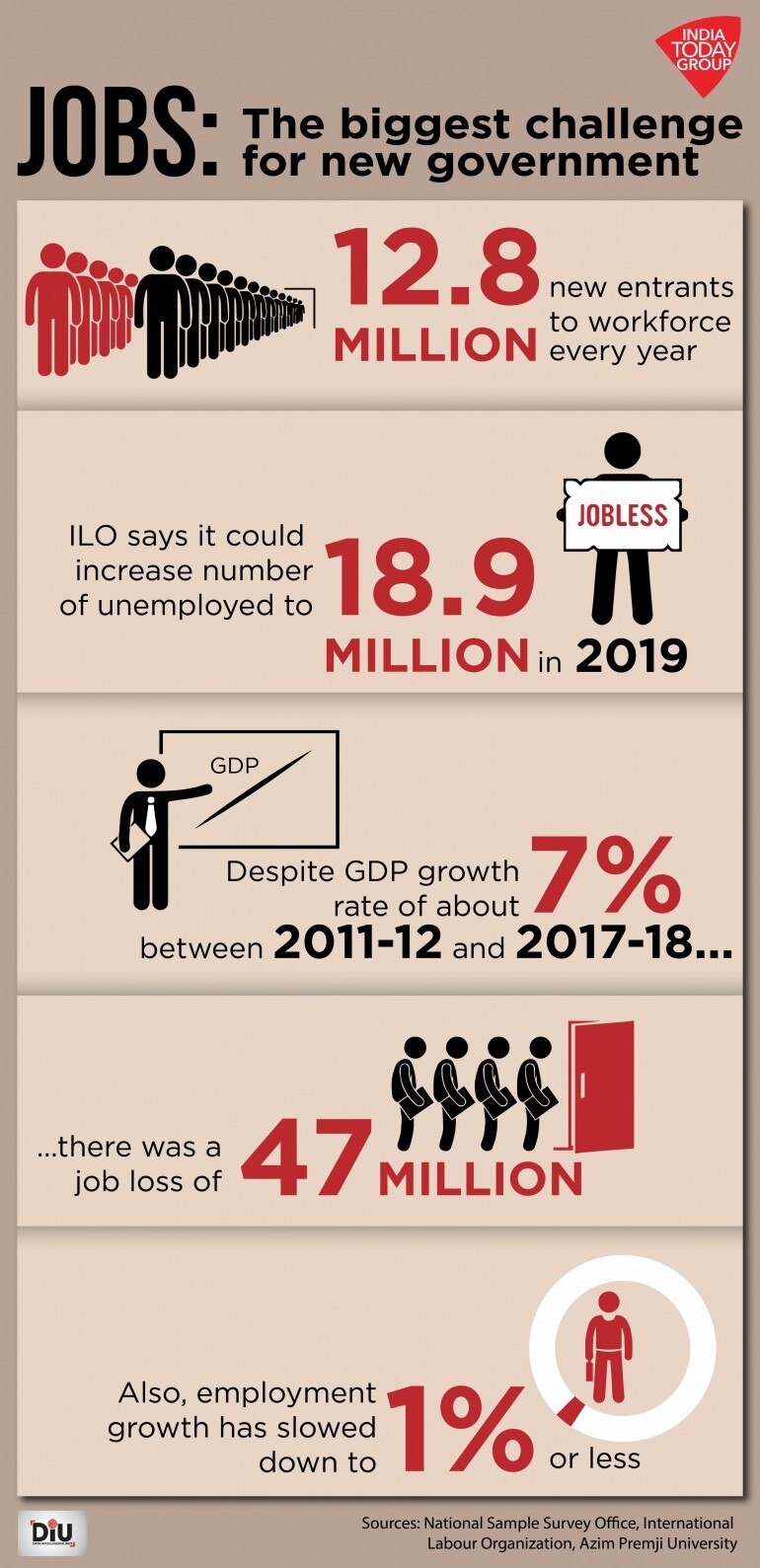

Irrespective of the political party or formation assuming power in New Delhi after the May 23 result, the biggest challenge for the new government would be to generate adequate employment opportunities - to take care of about 12.8 million new entrants to the workforce every year and those migrating out of agriculture to non-farm sectors (about 9 million people migrate for work annually).

Though no official data is available, the leaked report of the National Sample Survey Office's (NSSO) periodic labour force survey (PLFS) of 2017-18 showed that unemployment rate has risen to a 45-year high of 6.1 per cent. The 2018 International Labour Organization (ILO) report, World Employment and Social Outlook Trends, shows that the number of the unemployed is set to rise from 18.3 million in 2017 to 18.9 million by 2019.

All the poll surveys in the past couple of years have thrown up unemployment as the number one concern. Keeping such a large population in productive engagement is not only desirable for social harmony, but it is also essential to reduce poverty and inequality.

RECOGNISING THE CHALLENGES

The NSSO's PLFS report throws up a few things clearly: open unemployment rate has risen dramatically, from 2.2 per cent in 2011-12 to 6.1 per cent in 2017-18; workforce has shrunk (job loss) by 47 million during the period and that labour force participation rate (LFPR) has come down from 55.9 per cent to 49.5 per cent - that is more than half the working-age people (15-60 years) are out of the job market because there are no jobs.

This has happened when the GDP grew at a healthy rate of 7 per cent and more during all these years. As the Economic Survey of 2014-15 says, the power of growth to lift all boats depends critically on its employment creation potential but that potential has remained unfulfilled.

Both the Economic Survey of 2014-15 and Azim Premji University's study on the state of employment in India point out that economic growth is now producing less and fewer jobs. In the 1970s and 1980s, when GDP was growing around 3-4 per cent, employment growth was around 2 per cent. Since the 1990s and particularly in 2000s, GDP growth accelerated to 7 per cent but employment growth slowed down to one per cent or less.

What this means is, as Prof NR Bhanumurthy of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) explains, there is a need to shift production activities from low employment creating sectors to those that produce high employment.

In the meanwhile, an additional problem has surfaced. The Monthly Economic Report (MER) of the Finance Ministry for March 2019 shows that the real GDP has drastically slowed down - from 8.2 per cent in 2016-17 to 7 per cent in 2018-19.

This would suggest that there is an urgent need to revive India's growth story first without which there can be no possibility of creating employment.

IDENTIFYING THE AREAS OF FOCUS

The first task for the new government would, therefore, be to focus on economic growth. A closer look at government statistics shows that India's growth has been propelled by domestic consumption and government expenditure for the past few years, while the other two engines - private investment and exports - had failed. Now the MER shows that private consumption has collapsed, too.

In such a situation, any economist would suggest that the government expenditure (public investment) - which has also fallen from 1.9 per cent of GDP in 2016-17 to 1.7 per cent in 2018-19 - needs to go up to improve economic activity, create demand in the economy and attract private investment further down the line.

While the next government embarks on boosting public spending it is critical that it focuses on labour-intensive areas so that along with growth more employment is created - and for both unskilled and skilled labour.

In agriculture, such areas could be irrigation, extension services, cold storages and value-addition, expanding MGNREGS to create better quality assets, rural health and education infrastructure, roads etc. It is very well known that the most successful Asian economies pursued an agricultural development-led industrialisation pathway - like Japan, the Republic of Korea, Vietnam and China.

Other labour intensive non-farm sectors were identified and tracked by the government until 2015 - textiles and apparel, leather, metals and metal products, automobiles, gems and jewellery, transport, IT/BPO and handloom/ power loom etc. Construction, which once absorbed those migrating away from agriculture, IT/BPO, and tourism sectors are no longer producing sufficient jobs. Instead, health and education have emerged as top job creators, in addition to manufacturing.

A recent study shows that social sectors consisting of education, health, transportation and other public services, and hospitality, have significant potential for job creation. Besides, new emerging areas like robotics, artificial intelligence, 3D painting, big data analysis, cloud technology, etc. should be very much part of public investment plans.

NEED FOR NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT POLICY

When the Narendra Modi government came to power in 2014, it did set out to achieve the 'Lewisian' model of structural transformation - moving resources from the agricultural/traditional sector to the manufacturing/non-traditional sector - to take care of the unlimited supply of labour (unemployment). It sought to focus on 'Make in India' and 'Skilling India', declaring that, "Make In India, if successful, would make India a Lewisian economy in relation to unskilled labour. But 'Skilling India' is the one that has the potential to make India a Lewisian economy with respect to more skilled labour. The future trajectory of Indian economic development could depend on both".

However, over the years, both schemes faltered and failed to either achieve the structural transformation that they had aimed for or create sufficient employment. In more recent times, there was an attempt to even deny that there is a problem and hence, no initiative was taken to overcome it.

No comments:

Post a Comment