India has no data on jobs lost and businesses shut; no estimate of how many would have slipped into poverty or how income, health and education inequalities would have risen due to the pandemic. How will the Budget 2021 allocate resources appropriately to revive growth and bring development?

Prasanna Mohanty | January 30, 2021 | Updated 13:58 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | January 30, 2021 | Updated 13:58 IST

A few days to go for the first post-pandemic budget, there are great expectations from it, especially since the first advance estimates (AE) project the GDP growth to fall to minus 7.7% in FY21. The expectations are not just about quick recovery in the GDP growth but also revival of jobs, businesses and investments lost first to the pre-pandemic slowdown and then to the lockdown. It has been a long and painful wait for the aspirational Indians' dream of a better life promised to them in 2014.

These expectations have been fuelled by the promise of a once-in-100-years budget the Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman made at the CII Partnership Summit on January 5, 2021. There is, however, a big roadblock to this promise: The budget will be designed without critical information about socio-economic conditions of the people.

It is known that the lockdown led to massive disruptions in livelihood activities. Despite a stringent lockdown, India is among the top in the number of virus cases and deaths. All of these would have pushed millions of Indians into poverty and sharply raised inequalities of all kinds - in income, healthcare and education.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 62: Economic growth for whom and for what?

But the magnitude of these challenges is not known. Credible and adequate data is needed for the budget to determine the path to revive demand, incipiently pre-pandemic but worsened due to the lockdown. Revival of demand will lead to higher production of goods and services, which, in turn, will create appetite for credit and revive investment cycle.

How many jobs lost to pandemic and regained?

One of the basic information that the Indian government should have collected during the past 10 months (lockdown began on March 25, 2020) is to know the extent of job loss, directly linked to demand in the economy.

A guessing game wouldn't work here for two reasons.

Firstly, the labour ministry says 94% of India's total workforce is informal, which means there is little information about their current status. Apart from its accuracy (labour ministry has been repeating this number for a decade), since the two quarterly GDP numbers of FY21, that informs the AE, are based on formal sector indicators (except for crop production) there is no knowing what has happened to informal workers.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 61: All that's wrong with guaranteed MSP outside APMC

Secondly, the total number of India's workforce is also not known. The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) reports don't disclose it. It took the Azim Premji University to analyse the unit-level data of PLFS of 2017-18 to tell that India's workforce stood at 465.1 million in 2017-18 - down from 474.2 million in 2011-12. "This", the loss of 9 million jobs, the study said, "happened for the first time in India's history."

The PLFS of 2018-19 is out but its unit-level data is yet to be analysed to tell the size of workforce in 2018-19. For the budget, the status of 2019-20 and 2020-21 is more relevant but there is no way of knowing it because the government made no attempt.

The difficulty in guessing the extent of loss can be understood through the following exercise.

Assuming a 10% net job loss (jobs lost minus jobs regained) at the 2017-18 level, this would mean 46.5 million workers are without jobs or incomes. At 20% and 30% net job loss, the numbers will go up to 93 million and 139.5 million, respectively. Accordingly, consumption demand would be impacted.

These are far bigger numbers than they seem because the average family size is 4.7 (2011 Census). Assuming that a family has one working member, a 10%, 20% and 30% net job loss would translate to 218.6 million,437 million and 655.7 million people without sufficient income to spend. If a family has two working members, the corresponding numbers would be 109, 218.5 and 327.8 million.

How would a budget revive demand without knowing their numbers, whereabouts or job profiles?

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 60: India in a financial mess of its own making")

Poor response from AatmaNirbhar Bharat packages

The AatmaNirbhar Bharat packages allocated Rs 40,000 crore for MGNREGS and Rs 10,000 crore for Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Rozgar Yojana (PM-GKRY).

Both are relief work in rural areas, not jobs or regular sources of income.

As on January 26, 2021, MGNREGS provided work to 69.8 million households (HHs) and 101.7 million individuals. The average days of work provided were 45 days for HHs in FY21 (from April 1, 2020 to January 26, 2021) - far less than 48.4 in FY20 and 50.9 in FY19 or average of 47.7 days during FY16-FY20. The HHs which got 100 days of work were 3.2 million - far less than 4 million in FY20 and 5.2 million in FY19.

No such data is given for individuals.

Using the average family size of 4.7, the total number of people benefitting from the HHs getting 100 days of work (less than one-third of a year) is 15 million (3.2 million multiplied by 4.7) - 6.8% of the 218.6 million impacted by a 10% net job loss (as estimated earlier). The number would be too insignificant at 20% or 30% of net job loss.

The PM-GKRY (meant for migrant workers) was a zero-sum game to begin with as it amalgamated 25 existing rural development schemes. Any job to migrants would have been at the cost of the existing pool of rural unemployed. The additional allocation was announced on November 12, 2020.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 59: Quantum jump in fiscal spending is what India needs immediately

How many businesses shut and reopened?

Businesses too shut due to the pandemic. Loss of business is loss of income and production of goods and services. How many businesses shut and reopened? This answer is not known because the government did not collect this information either.

Let us consider MSMEs which have been hit the hardest but contribute significantly to the economy: contribute 45% to manufacturing output; more than 40% to exports; more than 28.8% to the GDP and provide jobs to 111 million (about 25% of total workforce). Of the total 6.34 crore MSME units, 99.5% are "micro" (6.31 crore), 0.5% small and 0.01% medium units.

The AatmaNirbhar Bharat packages extended credit facilities to MSMEs. On December 13, 2020, the finance ministry's latest status report said Rs 1.58 lakh crore of collateral-free credit had been disbursed (out of Rs 3 lakh crore earmarked) and "it is expected that 45 lakh units can resume business activity and safeguard jobs through this scheme".

This (45 lakh units) is 7% of the total MSMEs (6.34 crore). What about the rest 93% or 5.9 crore MSME units? Are they still shut? No information.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 58: The untold story of India's services sector

How many would have slipped into poverty?

It is widely acknowledged that the pandemic would push millions into extreme poverty.

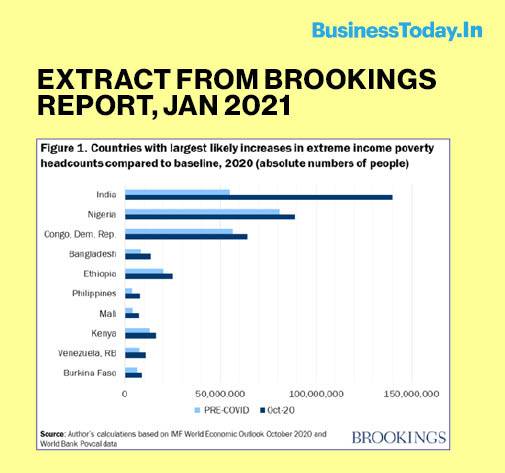

The Brookings Institute's "The impact of COVID-19 on global extreme poverty" report of October 2020 says India would surpass Nigeria to reclaim the title of the country with the highest number of "extreme poor" (per capita per day expenditure of $1.9) by "adding 85 million people to its poverty rolls in 2020".

It provided the following graph showing the number of "extreme poor" in India is likely to go up from 55 million (pre-pandemic) to 140 million.

The IMF's World Outlook Report "A Long and Difficult Ascent, October 2020" & "Fiscal Monitor: Policies for the Recovery" said 40 million Indians would turn "extreme poor" - rising from 80 million in 2018 to 120 million in 2020 - out of 90 million worldwide, contributing 44% to world's new "extreme poor".

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 57: When and how will industry take India to next level of growth?

Not just poverty, the pandemic will push up inequalities in income, health and education.

The Oxfam's "The Inequality Virus" report of January 22, 2021, which assessed the impact of lockdown worldwide, said the wealth of Indian billionaires went up by 35% during the pandemic, while millions of workers lost jobs (122 million workers lost jobs, of which 92 million were informal workers) and mass reverse migration happened. Over 300 informal workers died during the lockdown from starvation, suicides, exhaustion, road and rail accidents etc.

Health and education inequalities also spiked, it said. As for health inequality, it pointed at poor hygiene and access to healthcare, profiteering by private hospitals and also leaving out a large section of uninsured poor and middle class from the Ayushman Bharat programme that covers only BPL families. About education, it said the digital divide deprived education to the poor with 4% households having access to computers and less than 15% to internet connections in rural areas.

India made no attempt to know any of it. How will the budget be informed and address these challenges?

This is a critical lapse since the Niti Aayog's SDG Index 2019-20, released in December 2019, had clearly warned that poverty; hunger and income inequality had gone up in 22 to 25 states/union territories, out of 28 it mapped, in 2019.

How many migrants, health and police personnel died during the pandemic?

The Parliamentary session of September 2020 will be remembered for the government admitting abdication of its responsibilities to collect information and working in the dark.

In response to a series of questions about the pandemic's impact, the government said it had no data on (i) job loss of migrant workers due to the lockdown (ii) death of health workers and sanitation workers (iii) death of migrant workers who walked home (iv) death of policemen on pandemic duty (v) number of informal workers hit by the lockdown (vi) number of suicides by students etc. (For more read "Rebooting Economy 46: Who is designing India's growth path?")

There is yet another problem. The Indian government suppresses and ignores inconvenient data.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 55: Farmer producer organisations best bet for small, marginal farmers

How many Indians fell sick or died due to COVID-19?

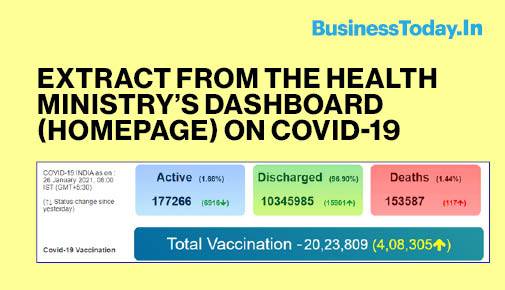

India is second in the world in total number of COVID-19 cases (10.7 million) and third in deaths (153,624) as on January 26, 2021.

Right from the beginning, the Indian official agencies did not give daily virus cases or the total numbers (except for total deaths which were added much later). They still don't. Indians were informed about the rising cases through non-government or outside agencies.

Here is an example from January 26, 2021.

Hiding known data has larger implications: India made no attempt to look at the impact of high infections and deaths on the finances of millions of households.

The only oddity in the above snapshot is "total vaccination" data, added to the dashboard since the vaccine rollout. The reason is far from transparency or accountability.

India is battling 'vaccine hesitancy', partly because the indigenous vaccine, Covaxin, was rolled out without its efficacy tested or known even to the regulator Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI). More than 10 days later (it was rolled out on January 16) its efficacy is not yet known because the third phase of clinical trials on humans is not complete. In fact, three days after it was rolled out, the company producing Covaxin, Bharat Biotech, released guidelines advising people not to take it in certain health conditions. By that time thousands, if not millions, would have been injected with it.

Efficacy is critical to a vaccine; otherwise, it might be as safe as water to take in but as useless as water to prevent the virus.

Suppressing inconvenient data started with the junking of the PLFS of 2017-18 in early 2019 for showing 45-year-high unemployment rate. It was released after the NDA-II government secured its second term. It never released the NSSO's 2017-18 survey that showed 'real" consumption expenditure had fallen for the first time in 40 years.

Here is another instance of first suppressing and then ignoring inconvenient data.

Sharp rise in suicides due to prolonged economic crisis

The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) stopped publishing data on suicides, collected by one of its units, the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB), in 2017 and 2018 as a nation-wide farmers' agitations (for higher MSP) continued.

When the NCRB released its reports in 2019 (posted outside the designated place to make it difficult to find) the number of farmers' suicides was seen going down, though still very high at over 10,000 a year, but a sharp surge was noticed in suicides by unemployed, self-employed and daily wagers - as the following graph shows.

No budget acknowledged this development nor tried to address it.

Long history of ignoring crises

There are good reasons to be sceptical about the forthcoming budget.

India's growth story was, quite apparently, derailed by the twin shocks of demonetisation (2016) and GST (2017). No data was ever collected to know the damages caused. No budget acknowledged the continuing job crisis, impoverishment, loss of businesses and slowdown before the pandemic hit. Consequently, no roadmap to overcome the challenges was ever spelt out.

Why would the expectations be different this time?

Moreover, what would it do when it does not have the critical socio-economic data to work with?

No comments:

Post a Comment