Several studies throw up structural, logistical and financial challenges to the growth of crop insurance in India, jeopardised by apparent profiteering by insurance companies

Prasanna Mohanty | December 23, 2020 | Updated 23:17 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | December 23, 2020 | Updated 23:17 IST

Crop insurance is one of the key elements to stabilise farmers by compensating for crop losses arising out of drought, flood and other causes. In 2016, India overhauled crop insurance to expand its coverage of farmers and farm areas. Initially, it did expand the coverage but since then it has seen a downward slide, one of the key reasons for this being visible profiteering by insurance companies.

Here is a broad look at the crop insurance scenario.

Profitable business for insurance companies, not for farmers

In November 2018, the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) released its 2017-18 annual report with a table "Crop Insurance during Financial Year 2017-18 as on 31-03-2018" providing interesting insights into the crop insurance business.

A particularly disturbing one was that private insurance companies saved a great deal of the premium they received from farmers and governments, while public insurance companies did the opposite.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 52: The unfinished agenda of land reforms nobody talks about

The following graph maps the difference between gross premium received and compensation claims reported (not actual disbursal of claims which will be lower) for both private and public insurance companies. The public insurances are marked 'PSU' in the graph and the data includes all crop insurance schemes of Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY), Revised Weather Based Corp Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) and Coconut Palm Insurance Scheme (CPIS).

13 private companies generated a surplus of Rs 2,725 crore but the five PSU ones recorded a deficit of Rs 3,484 crore in 2017-18. Net effect: a deficit of Rs 759 crore over the premium received. (The IRDA report pointed out that the claims included previous year's payment in RWBCIS also.)

This table (Table 1.95) did not appear in the 2018-19 annual report of the IRDAI, nor is it likely in the 2019-20 one since newspapers went to town with this.

Why this happened? There could be various reasons. According to a state government official dealing with the PMFBY, this could be primarily because private insurance companies tend to bid for areas less vulnerable to crop loss and hence, less liability.

The situation was a little different the previous year, 2016-17.

The IRDAI's 2016-17 annual report provided details only about PMFBY, not RWBCIS and CPIS and hence, this data is not comparable to 2017-18. In this instance, all insurers, private or public, reported a surplus. Net effect: a saving of Rs 3,532.7 crore.

This is easy to understand. If crop loss is less, insurers make a surplus, and if it is more, they report a deficit. Both private and public insurers are also insured with public sector insurer General Insurance Company (GIC), which underwrites such losses.

However, there was a big brouhaha over this (huge savings from the premium) and farmers and some state governments withdrew from it, reducing the coverage in subsequent years.

That is because the premium is paid by farmers and the central and state governments.

Under both PMFBY and RWBCIS, farmers pay 1.5% to 5% of the sum assured and the rest by the central and state governments equally. In PMFBY, farmers have paid 15-19% of the total premium during FY17-FY20 and the rest by the governments (80% or more). Under the earlier scheme of Modified of National Agriculture Insurance Scheme (MNAIS), the governments paid up to 75% of the premium (subsidy).

Why not pay directly to farmers for crop loss?

There are good reasons why the insurance subsidy (premium) should go directly to farmers' bank accounts, rather than to crop insurance companies.

Firstly, 80% or more of the total premium is paid by the central and state governments.

Secondly, the state governments carry out crop cutting experiments (CCE), twice a year, to decide crop loss.

It is logical then that the compensation be paid directly (DBT) to farmers, like the PM-Kisan scheme.

Earlier this month, the Union Cabinet directed that the sugarcane subsidy of Rs 3,500 crore be directly paid to sugarcane farmers, instead of sugar mills - evidence that post-1998 (when licensing for sugar mills was abolished) deregulation of sugar sector has not really helped farmers.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 50: Economic reforms for whom and for what?

How crop insurance trends have changed after PMFBY

Official statistics show the trend in premium collected, claims reported and claims paid for PMFBY and RWBCIS - as presented below.

There are two noticeable features: (i) premium received is consistently more than reported claims and (ii) paid claims are less than reported claims.

That was not the case earlier.

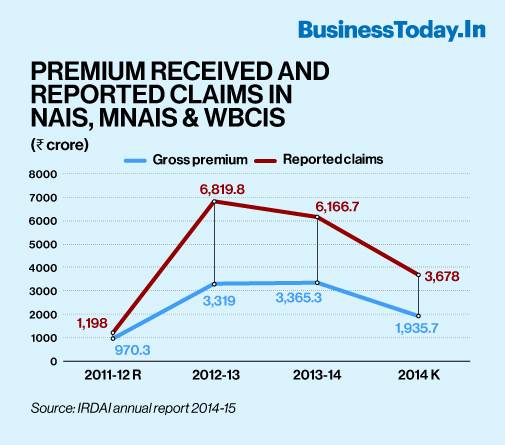

The IRDAI's 2014-15 annual report provides a comprehensive picture of earlier schemes of the National Agriculture Insurance Scheme (NAIS) of 1990-2000, Modified NAIS (MNAIS) of 2010-11 and Weather Based Crop Insurance (WBCIS) of 2007. The column on 'paid claims' is missing in its data. (The PMFBY replaced NAIS and MNIS and WBCIS was replaced with Restructure WBCIS (RWBCIS) in 2016.)

Notice the difference. The reported claims are consistently higher than the premium received.

What changed in 2016 and why?

Private insurance companies did get into the business earlier (during the UPA era) but their presence was minimal, reveal official sources. The IRDAI does not provide data on their participation in the pre-2016 schemes. In 2016-17 and 2017-18 (PMFBY and RWBCIS were introduced in 2016 Kharif) the private insurance companies had a share of 46-47% in total premium received.

Assistant professor Kulwant Singh Mehra of the Chandigarh-based Centre for Research in Rural and Industrial Development (CRRID) carried out an evaluation of the PMFBY in 2018 on behalf of Haryana's planning department. His study covered six districts of Bhiwani, Fatehabad, Jind, Hisar, Rohtak and Sirsa.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 49: Who needs corporates to run banks and how will it help Indian economy?

His findings are yet to be published, but here is what this study found about the private insurance companies: (i) high under-estimation of crop loss in collusion with government officials carrying out CCEs (ii) unnecessary rejection of claims, often by using technical jargons (iii) claim settlements delayed (iv) farmers unaware and unable to get in touch with private insurers because they are yet to provide block-level infrastructure and (v) no grievance redressal mechanism (the contact numbers provided often don't work).

Mehra's study concluded that the objectives of the PMFBY (expanding crop insurance and bringing private investment) are good but riddled with old problems like poor awareness, poor implementation and monitoring, poor coordination among banks, agriculture department and insurers and poor private investment in infrastructure (including lack of awareness campaigns) etc.

That private companies are profit-oriented is a given. In 2019, four private insurance companies hit the headlines by declaring that they were opting out of the PMFBY for 2019-20 (for both Kharif and Rabi) because claim ratios (claims paid to premium received) were very high in the previous seasons, leading to loss in business.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 48: Do tax numbers show a healthier economy?

Why are farmers and states averse to new crop insurance?

That the new insurance schemes of PMFBY and RWBCIS expanded the coverage and brought a higher number of farmers and farms is not in doubt. The cause of worry is the subsequent fall in coverage.

The following graph maps the number of farmers and farm areas in FY18 and FY19. The fall is reversed for FY19 Kharif (marked FY19 K in the graph) but that is only a part of the FY20 cropping seasons (Rabi numbers not available).

Why the number is falling is known.

Farmers and several state governments started pulling out of the PMFBY for reasons that included profiteering by insurance companies, high rejections and delayed payments. Several states, including Bihar, West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Jharkhand floated their own crop insurance schemes, protesting that insurance companies.

As a result, the central government made several changes in both PMFBY and RWBCIS in February 2020, the key ones of which were: (i) crop insurance is now voluntary for farmers (ii) a drastic cut in central government share of crop insurance subsidy from 50% to 30% for un-irrigated areas/crops and 25% for irrigated areas/crops and (iii) flexibility to states to select crops for insurance cover.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 47: Do India's fiscal numbers suggest a quick turn-around?

Making it voluntary for farmers will reduce the crop insurance cover further, as the central government acknowledged while announcing the changes. Until February 2020, crop insurance was compulsory for those availing crop loans and formed the bulk of insured farmers (75% in 2016-17), the rest being non-loanee farmers who opted for insurance voluntarily.

A substantial cut in the central subsidy (by nearly half) will also adversely impact the coverage and may prompt more states to opt out.

Challenges in crop insurance

The biggest challenge for farmers continues to remain the unusual way crop insurance works in India: Farmers are not provided with insurance policy documents or receipts of premiums from banks or insurance companies that would tell them who their insurer is or received their premium (deducted at the time of taking loans).

The IIM-Ahmedabad carried out an evaluation of the PMFBY and published its findings in 2018. The report identified several challenges, the key ones being: (i) farmers in low risk areas try to avoid paying premium (ii) insurance companies not interested in non-loanee farmers as that would entail additional costs, like field verification (iii) inadequate and "highly ill-managed" CCEs which are prone to human error and manipulation by different stakeholders (iv) delay in claim settlements and (vi) skewed distribution of risks - 75% of premium coming from 25% of districts which get 75% of the total claims.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 46: Who is designing India's growth path?

Talking about negative perception of crop insurance, it said "insurance companies made nearly a profit of Rs. 7,000 crore in 2016-17 with a net operating margin of 25%".

The IIM-Ahmedabad's second study on the subject was published in 2019, which concluded, among others, that farmers would prefer remote sensing or rainfall indices to CCE to decide crop loss and would be willing to pay an even higher premium if compensation is paid on time.

A private think tank, Observer Research Foundation (ORF), also studied the PMFBY and published its findings in 2019. It concluded that the scheme faced several structural, logistical and financial obstacles even though it was an improvement on earlier crop insurance schemes.

It listed several obstacles, two of which are: failure of banks to give loans to small and marginal farmers and high profit of insurance companies at the cost of farmers.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy 45: What is AatmaNirbhar Bharat and where will it take India?

No comments:

Post a Comment