Developed economies have sound, fiscally-supported systems to respond to workers' distress in normal times, which they scaled up several notches with higher fiscal support to fight the current crisis. India doesn't have such a system nor did it rise up to the crisis; it isn't even tracking job loss

Prasanna Mohanty | August 30, 2020 | Updated 08:35 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | August 30, 2020 | Updated 08:35 IST

One of the harsh realities of India in the current economic crisis is that very little has been done for its unorganised sector workers, who have been the hardest hit and constitute 94% of its total workforce (437 million of total 465 million workers).

The plight of migrant workers - hundreds of thousands of them walking home from urban areas to the hinterland, some perishing on the way - was the most visible part of it. Train services did start in May (more than a month after the country was abruptly shut down with less than four hours' notice from the midnight of March 24-25) and ferried 6.29 million of them, but many still kept walking because of mismanagement and confusion.

The government and Indian Railways did not shy away from charging the crisis-hit migrant workers fully for their tickets. State governments stepped in to pay.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXII: Why is India reluctant to provide unemployment allowance?

Indian Railways is a fully public-owned entity; built, maintained and run with taxpayers' money. It made a cool profit of Rs 428 crore out of this operation, as the Railway Board subsequently revealed in an RTI reply on July 23, 2020 - reproduced below.

India's half-measures and little fiscal support to crisis-hit workers

The government took a few half-measures to address the crisis that hit its workforce due to its own untimely and unplanned lockdown with no time to prepare.

The first was for the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) to issue a circular on March 29 asking private enterprises to pay wages/salaries to their employees for the lockdown period. It involved no government expenditure (taxpayers' money).

On May 17, this directive was withdrawn after the Supreme Court (SC) stayed it on appeal from private enterprises which said the government was passing the burden on to them for a period when work was shut but not using the Employees' State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) fund (meant for organised sector workers) to help.

The second was to facilitate workers (organised sector) to withdraw from their own post-retirement contingency fund, the Provident Fund (PF), jeopardising their future security. This is a contributory fund to which employers and employees pay their share. This involved no government spending either.

Such was the government push for workers to exhaust their own future contingency money (PF) that of the 20 press statements the labour ministry issued between April 18 and July 8, 2020, 12 were about this and other PF related matters. The details can't be updated now because the relevant site is down for several days. (For more read "Rebooting Economy VI: Is Modi govt ignoring job crisis in India or unable to tackle it? ")

The third was fiscal support, paying PF contributions for establishments having up to 100 employees, 90% of which earn less than Rs 15,000 a month. This was for a period of six months from March to August 2020 at an estimated cost of Rs 4,800 crore to the exchequer (taxpayers' money).

The fourth was to facilitate construction workers (unorganised sector) to access their own welfare fund of Rs 52,000 crore, lying unutilised for decades due to government mismanagement. This fund is collected from cess on builders and involves no government spending.

The fifth measure was announced on August 20, 2020 to provide unemployment allowance to insured workers (organised sector) under the ESIC. This too is contributory and involves no government spending.

The idea of this allowance came from private enterprises in April when they opposed the MHA circular of March 29 asking them to pay wages for the locked down period.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXI: Will NEP 2020 bring quality and equity in education?

According to ESIC officials, it is expected to benefit 3.03 million out of 8.04 million who have seemingly lost their jobs since they stopped contributing in April-May 2020.

The sixth measure was additional fiscal support of Rs 40,000 crore for the rural job guarantee scheme MGNREGS, but those who avail this relief are not part of the official count of 465 million workforce.

Supreme Court's reluctance to stand up for workers

The Supreme Court did not come to the rescue of migrant workers either.

It repeatedly dismissed desperate pleas for help from multiple quarters for two months when hundreds of thousands were walking home, jobless, shelter-less and starved.

It dismissed a plea for wage support from the government with the Chief Justice of India SA Bobde asking their counsel Prashant Bhushan in open court: "If they are being provided meals, then why do they need money for meals?" The stark realities missed the court's attention.

The SC also stayed the MHA's notification asking employers to pay wages/salaries for the lockdown period and stopped the central and state governments from taking coercive actions against them. It said it can't force private entities to do that either. It could have directed the government to pay from taxpayers' money, but it didn't.

Having taken such stands, the apex court, on May 26,2020, took "suo motu" cognisance (on its own) of the migrant workers' plight and said: "The adequate transport arrangement, food and shelters are immediately to be provided by the Centre and State governments free of cost."

This was irrelevant by then. The migrant workers had been walking for more than two months (lockdown began on March 25) and 26 days had passed since the central government was forced to start train services to take them home and make profit (Rs 428 crore) out of it.

The apex court did not take cognizance of unpaid wages of migrant workers for the days of March they had worked and complained to whoever would listen (mainly media) nor the need for monetary support in subsequent months that left them jobless, shelter-less and starving with no fault of theirs.

That is not what is expected in any democratic country. No other country in the world witnessed the hardship and indignity that befell the Indian workers.

The developed economies take good care of their workers, not only in economic crisis but also in normal times when workers fall on bad times.

Here is what they are doing.

OECD countries helped 50 million workers through job retention schemes

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (ORCD), an elite club of 36 developed economies across the world, released a report on August 3, 2020 detailing how their member countries took care of their workers in the current economic crisis.

It said the main policy tool to contain job loss and social fallout of the economic crisis was "Job Retention (JR) schemes".

The report elaborated on it: "By May 2020, JR schemes supported about 50 million jobs across the OECD, about ten times as many as during the global financial crisis of 2008-09. By reducing labour costs, JR schemes have prevented a surge in unemployment, while they have mitigated financial hardship and buttressed aggregate demand by supporting the incomes of workers on reduced working time."

India has no such scheme but could have designed one to meet the crisis.

The report gave detailed accounts of what some countries did and all of it involved higher fiscal spending.

About the US, it said apart from its existing unemployment allowance scheme (predates the pandemic) - weekly $600 for four months - it launched several new measures specifically for the current situation.

These included Short-Term Compensation (STC) programme, CARES Act of 2020, Paycheck Protection Programme (PPP) and Employee Retention Tax Credit (ERTC). These programmes provide loans to pay salaries which are forgiven if employment and compensation (salary/pay) levels are maintained, refundable tax credit to firms and many more such measures.

A CNN International report of August 20 said that by the week ending August 8, 14.8 million Americans were on regular claims of unemployment allowance and "all in all, nearly 28.1 million Americans were claiming benefits under the various government programs available in the week ending August 1".

Germany runs "Kurzarbeit", a social insurance programme in which employers reduce working hours instead of laying their workers off in troubled times. Workers get paid for actual hours of work plus 60% (67% for workers with children) for the non-work hours. The government fully reimburses the cost to firms. This programme was relaxed to allow government reimbursement if 10% of a firm's workforce is affected by cuts in working hours, from 30% earlier (pre-pandemic).

Its public employment service reimburses 100% of social insurance contributions for lost work too.

France has a similar system (as do several European countries) to prevent workers' lay-off by reducing working hours, called "Activite Partielle". The French government allows firms to invoke the health crisis as "force majeure" and extended the scheme from six to 12 months.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XIX: How India relies on low-paid ad hoc teachers for schooling children

The report said how it works: "All employees with a contract (whether permanent or not) are eligible and receive 70% of their gross wage from the employer. During the COVID-19 crisis, most employers do not bear any cost for hours not worked, as the state reimburses what they pay to employees up to a cap of 4.5 times the hourly minimum wage."

The Oxford dictionary defines "force majeure" as "unexpected circumstances, such as war, that can be used as an excuse when they prevent somebody from doing something that is written in a contract".

India is diluting social security cover for workers

India has been diluting and curtailing, instead of strengthening and expanding social security cover.

Here are two examples.

One, on June 13, 2019 the government reduced the rate of contributions (employers plus employees) under the ESI Act of 1948 (applicable to factories having 10 or more workers and earning a maximum of Rs 21,000 per month) from 6.5% to 4%. The purpose was to increase take-home salary of workers (they are organised sector workers) and it was officially described as a "historic decision". It came into force on July 1, 2019.

The ESIC officials are, however, worried. The total contributions in FY20 (audited report is yet to be released) fell by about Rs 2,000 crore to Rs 22,000 crore. The fall would have been sharper (which would be the case in next fiscals) had the new rate come into force on April1, instead of July 1.

ESIC has built up a corpus of Rs 91,444 crore (as on March 31, 2019) and its annual savings in the past 10 years have been 60% or more of the total contributions. The corpus is used to support workers and their families falling on bad times like job loss, death, disability, healthcare and retirement benefits like pension and continued healthcare.

Two, the Code on Social Security 2019, which was introduced in the Lok Sabha last year, to provide comprehensive social security cover to 437 million unorganised workers, removed the provision for unemployment allowance for those that existed in its earlier draft.

This was revealed by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Labour, which examined it and submitted its report (Number 9) in July 2020. The panel took the government to task for lofty promises without any substance as would be clear from its diagnosis or prescriptions.

The prescriptions included: (i) incorporate unemployment allowance for unorganised workers, which is "the biggest gap" in the Code (ii) make universalisation of social protection for all unorganised workers "legally binding" and "within a definite time frame" (iii) give "unequivocal and conclusive definition" of unorganised workers, remove multiplicity of their registration and create national database on them (iv) quantify expenditure and source of funding for social security schemes (v) study welfare schemes to know what to do and how etc.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XVIII: Does quality education really matter to India?

There are many other steps that the government needs to take.

The most important thing is to provide an estimate of its total workforce, its distribution across sectors and status (whether organised, unorganised, formal or informal) in absolute numbers.

The official Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFSs) provide unemployment rate and distribution of workers in percentage terms but none in absolute numbers. That requires a study of its unit-level data, which is for domain experts to do. Those who prepare PLFS reports can do it easily but they don't for reasons not very convincing (like, they don't have population projections for a particular year).

The labour ministry says India has 465 million workers; of which 28 million (6%) are organised sector workers and 437 million (94%) are unorganised sector workers. But where did it get this data from is not revealed. Their sector-wise break up (numbers) is also not given.

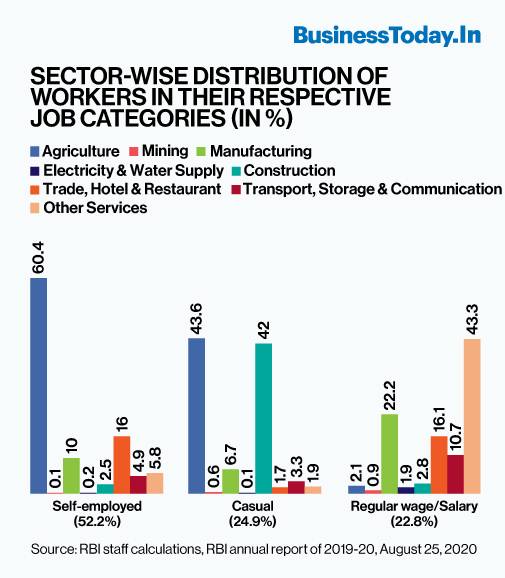

The RBI's annual report of 2019-20, released on August 25, 2020, provided its own estimates on distribution of workers, sector-wise and employment category-wise, in percentage of respective employment category.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XVII: Why governments promote shadow banking

The data is mapped below. The numbers in parenthesis show the share of different categories of employees in the total workforce, as provided in the PLFS report of 2017-18.

Even more important and critical in the current crisis is to find out how many have lost their jobs in which sector and rush them immediate monetary and other support (from taxpayers' money).

An unhealthy and insecure workforce like that of India doesn't build rich and prosperous economies nor capable of quick rebound in the time of crisis.

No comments:

Post a Comment