It would be naive to expect agriculture providing jobs to about 43% of the workforce and sustaining 70% of the population living in rural India with a meagre share of 14.5% in national income (GDP) to drive growth, especially when it is going through unprecedented job and income loss

Prasanna Mohanty | September 17, 2020 | Updated 13:55 IST

Prasanna Mohanty | September 17, 2020 | Updated 13:55 IST

The government is banking on a strong agriculture-led economic revival since it is the only sector that witnessed a positive growth of 3.4% (GVA at basic price) in Q1 of FY21, the rest recording big negative numbers to take the overall rate to minus 22.8% in GVA (minus 23.9% in GDP).

The other reason for the government's optimism is 8.54% higher sowing area for Kharif crops. Since Kharif crops are harvested in October-November, by which time Q2 of FY21 (July-September) would be over, the actual harvest would be anybody's guess for Q2.

Nevertheless, does 8.5% growth in Kharif sowing area really mean a bumper Kharif harvest? Does a 3.4% growth in agriculture in Q1 mean agriculture can drive growth or revive the economy? Is there reason to be optimistic about the rural economy?

Here is a reality check.

Q1 agriculture growth highly exaggerated

The graph below maps quarterly growth in agriculture (GVA at basic price) to show how this sector providing jobs to nearly half of India's total workforce (53.2% rural male and 71% of rural female engaged in agriculture, according to the PLFS 2018-19 data) has been growing since FY23.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVII: Fiscal mismanagement threatens India's economic recovery

Going by the cyclical and monsoon-dependent nature of agricultural growth, the Q1 of FY21 number is not exactly remarkable.

Besides, agricultural economist Prof. Vikas Rawal of the Jawaharlal Nehru University draws attention to a major flaw in the Q1 growth estimates for agriculture.

The government's August 31 statement "estimates of Gross Domestic Product for the first quarter (April-June) of 2020-21" reveals a significant change in calculation.

It says for estimating growth in milk, egg, meat, and wool for the livestock sector and dairying and fish production for forestry and fisheries sector in Q1, it used "production targets", not actual production.

That has never been the case in spite of the obvious shortcomings in the quarterly GDP estimates.

The quarterly GDP estimates are based on select organised sector indicators to map unorganised services sector as well but not agriculture, for which actual production figures are used. A case in point is the two previous Q1 estimates for FY20 and FY19.

But that is not the case for Q1 of FY21.

Since these two subsectors (livestock and forestry and fisheries) accounted for 47% of GVA in Q1 of FY20, the error margin in using "production targets" would apparently be exaggerated. (The rest 53% of agriculture GVA was on account of crops, including fruits and vegetables.)

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXVI: Derailment of economy is not 'Act of God', it is 'Art of Misdirection'

There is every reason to believe that the livestock and forestry and fisheries subsectors were seriously impacted by the sudden lockdown. All activities came to a standstill for several weeks, farm labour disappeared, transport was shut, mandis were non-operational despite exemptions granted and demand plunged, forcing farmers to dump milk and vegetables. The supply chain had been completely disrupted.

Prof. Rawal also contests 3.4% growth in agriculture GVA on the basis of mandi sales too.

He compiled and compared market transactions in agricultural produce from the government-run portal 'agmarknet.gov.in' for Q1 of FY20 and Q1 of FY21. He found a significant fall in mandi sales (in value) across India, ranging from minus 31% for cereals to minus 90% for flowers.

His findings are presented in the following graph.

Agriculture production data (or any production for that matter) means little for GVA estimates if these produce, particularly the perishables which perish in days and weeks, are not sold in the market.

Assuming that agriculture can drive or lead economic revival is flawed for another reason.

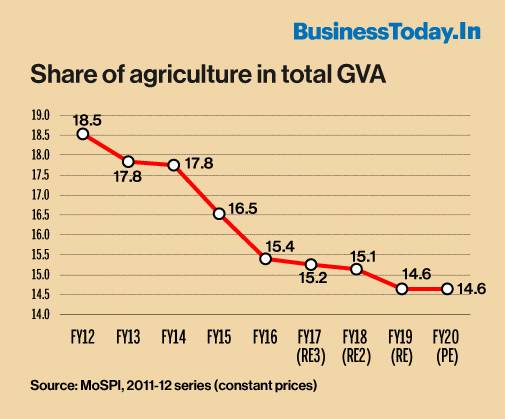

The following graph maps how the share of agriculture has been falling consistently since FY12, reaching 14.6% of the total GVA in FY20. For a meaningful impact on the rest 85.4% of the economy, the agriculture GVA has to register a quantum jump.

Here is how.

The average growth in the quarterly agriculture GVA for the past 20 quarters is 4%. Assuming it would grow by 5% in Q2, the addition to the overall GVA would only be 0.7%.

There are other reasons to be sceptical too.

Kharif crop harvest likely to fall

The Kharif sowing may be higher by 8.5% in area but latest ground reports suggest severe damage to crops due to deviant monsoon.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXV: How a series of economic misadventures derailed India's growth story

According to a news report of September 11, Madhya Pradesh witnessed a deficient rain in July and heavy rain in August-end, both damaging soya bean and pulses (urad). The state is the largest producer of these crops. Excess August-end rain has also damaged Kharif onion in Maharashtra and north Karnataka.

Another report of August 26 says Gujarat, the largest producer of cotton and groundnut, received excess rain in August, damaging its crops. This happened in Telangana too.

All these would reduce Kharif harvest.

Threat from rapid spreading of COVID-19 to rural India

In the meanwhile, the COVID-19 cases are rapidly rising in rural India, threatening economic growth further.

A September 3 research paper by the largest public sector bank SBI, "Three Months After Unlock", shows the share of new virus cases from rural districts has increased dramatically in the months of July and August (part of Q2).

From 24% of new cases in April, rural districts contributed 51% in July and 55% in August. Among the top 50 worst-hit districts in new cases in August, 26 are rural ones from Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh. Four of these districts contribute more than 10% to respective GSDP.

The report also expresses concern over "excess" rainfall, at least in five of those districts in August damaging Kharif crops.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXIII: What stops India from taking care of its crisis-hit workers?

Further, it points out that though tractor and two-wheeler sales increased in July and August, fertiliser sales and diesel consumption dropped significantly in those months - as the graph below shows.

A drastic fall in fertiliser sale (green line) in July and August is of particular concern because that is the time for fertiliser use. Kharif crops are sown in June-July.

There are other indicators too.

The RBI's August 25 report (Annual Report of 2019-20) said: "Meanwhile, high frequency indicators that have arrived so far point to a retrenchment in activity that is unprecedented in history. Moreover, the upticks that became visible in May and June after the lockdown was eased in several parts of the country, appear to have lost strength in July and August, mainly due to re-imposition or stricter imposition of lockdowns, suggesting that contraction in economic activity will likely prolong into Q2."

Massive loss of jobs and incomes in rural India

There are plenty of indications that job loss and income loss are far greater in rural areas, compared to urban areas, even though the government has deliberately adopted an ostrich-like attitude by not tracking job and income losses. For a government to then create hype that agriculture would lead the economic recovery amounts to leading the Indians down the garden path to their eventual doom.

The SBI research paper shows that the steam has run out of the rural job guarantee scheme MGNREGS in July and August - as the graph below shows. Both employment and average wages fell drastically, indicating that funds dried up.

The fall in the average wages in rural areas would mean any or both: (i) fake entries for MGNREGS jobs provided because its wages are fixed and the average can't fall or (ii) drastic fall in other rural jobs, indicating a growing loss of jobs and incomes.

The latest survey on rural distress comes from Gaon Connection, a rural media platform and Centre for Study of Developing Societies (Lokniti-CSDS), which was published in mid-August.

Its main findings (based on interviews with 25,300 respondents from 179 districts in 20 states and three union territories) two months into the lockdown were: (a) 71% households reported drop in monthly income (b) over 68% faced "high" to "very high" monetary difficulties (c) 23% borrowed money, 8% sold valuables (phone, watches), 7% mortgaged jewellery and 5% sold or mortgaged land (d) 56% dairy and poultry farmers faced difficulty to sell, 35% did not get the right price (e) more than half of farmers harvested their crops but only a fourth could sell them on time (f) work shut down for 60% skilled and 64% manual labourers and (g) only 20% found MGNREGS work.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXII: Why is India reluctant to provide unemployment allowance?

An earlier study, in April, by the Chicago University and University of Pennsylvania had shown that rural households had been hit harder than their urban counterparts. It said that "protective effect" found in highest-income households is a predominantly urban phenomenon, with 81% rural high-earning households experiencing a decline in income. The lowest income group was hit the most with more than 80% reporting a decline.

Naive to expect agriculture to drive growth

There are many reasons to discount faith in agriculture to drive economic growth.

Not only 70% of Indians live in rural areas and largely depend on agriculture, but its share in the total workforce is also around 43% (43.2% in 2019, according to ILO database). Besides, 55% of the total agriculture workforce is landless labour and they number 112 million. (For more read "Coronavirus Lockdown I: Who and how many are vulnerable to COVID-19 pandemic")

Add millions of migrants going back due to the lockdown and job loss sharing the same total agriculture pie of 14.6% of national income and a clearer picture would emerge.

India's recent rural development programmes are unlikely to make any difference.

The flagship PM-Kisan scheme provides Rs 2,000 a year (Rs 500 a month) to a farmer, which is grossly inadequate for one person's survival. The MGNREGS work is a relief measure (less than minimum wage for rural areas and agriculture wage) providing jobs for a maximum of 100 days, but the average days of work given in five fiscals, including FY21, remains 45 days.

The Garib Kalyan Rozgar Abhiyaan (GKRA) launched for migrant workers who went back home is an amalgamation of existing rural development schemes with no additional funding and a zero-sum game since it would be at the cost of existing unemployed finding succour through these schemes.

Also Read: Rebooting Economy XXI: Will NEP 2020 bring quality and equity in education?

The much-hyped Agriculture Infrastructure Fund of Rs 1 lakh crore is part of the Rs 21 lakh crore relief and credit package announced in May without proper plans or schemes in place. It is a misleading scheme since the government is not going to set up a fund or provide loans to farmers.

This is a 10-year plan of facilitating loans from banks and financial institutions for which the Centre promises to provide 3% interest subvention (old scheme for any agricultural loan) and credit guarantee (same as pandemic relief for MSMEs). The actual financial outgo in the current fiscal year will be zero since the moratorium on repayment is at play and would be applicable for such loans too.

With such policies and programmes for a sector which is already enfeebled and yet most Indians have no choice but to fall back on it for mere survival, only the very naive would believe that agriculture can drive economic growth or bring it back on track.